He was one of the original thinkers who helped mankind take flight.

And such was the dedication and commitment that George Louis Outram Davidson displayed towards his ambition to reach for the skies in the late 1890s and early years of the 20th Century, he became known across the north-east as Fleein’ Geordie.

This real-life Caractacus Potts – the eccentric main character in Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang – was involved in creating bold plans, featuring such vehicles as air cars and gyrocopters, and he had the means to turn his dreams into reality.

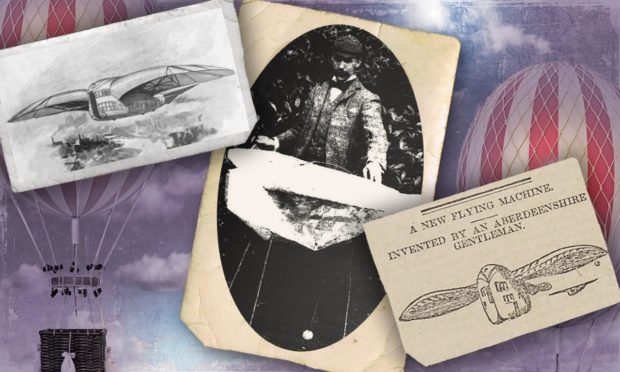

So there was much excitement in September 1898 when the Aberdeen Journal carried a story with the headline: “New Flying Machine Invented”.

The paper reported how the 40-year-old Davidson had devised proposals for the construction of an aircraft that would soar into the stratosphere and, in future, carry upwards of 20 people from different terminals.

He had previously applied for the patent and created the template for a company called Davidson’s Air-Car Construction Syndicate with £20,000 investment – a massive amount of money at the time.

And he invited the public to watch a trial of his ground-breaking machine.

Davidson wanted to fly like a bird

From his childhood in and around Banchory, this redoubtable individual who loved machines and machinery was obsessed with trying to prove that, if birds could fly, then man should be able to follow in their slipstream.

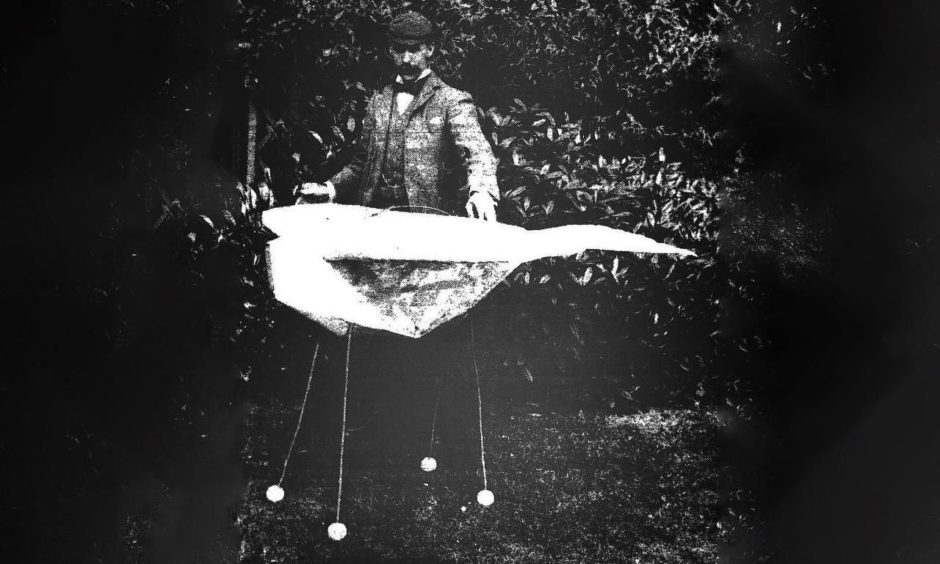

His earliest glider device, tested methodically at various sites in Banchory, was designed to leave terra firma in a series of lifts followed by horizontal, bird-like flights with an airflow regulated by flaps in the wings.

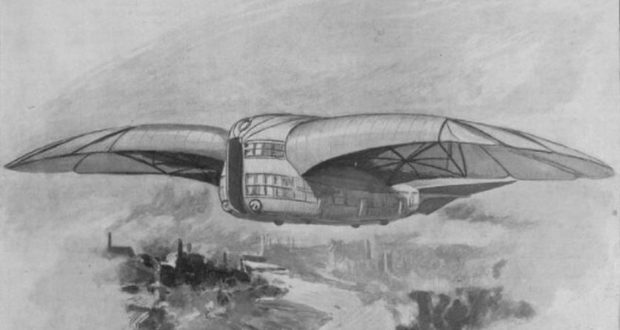

The idea, which he patented in 1896, was that his air-car monoplane, with a wingspan of 30 metres and a fuselage of 14 metres, would carry passengers from one city to another – and possibly even across the Atlantic in the future.

In September 1898, a collection of curious press correspondents and local residents gathered in Banchory to witness the trial of one of a number of scale models he had constructed to test his design.

But although there was much optimistic talk in the Aberdeen Journal and other contemporary newspapers, the craft failed to perform as expected and eventually crashed, although Davidson was mercifully unhurt in the incident.

Davidson was a genuine pioneer

A syndicate, established in 1897, raised in the region of £20,000 for construction of the air-car and to purchase the patent rights from Davidson, but, following the unsuccessful trial on Deeside, the project lapsed.

However, the enterprising Scot was undaunted and, just the following month, in October 1898, delivered a well-attended lecture entitled Mechanical Flight to a distinguished audience in London.

He outlined his belief that the day would come when a passenger would be able to fly from Manchester to London or Edinburgh to Aberdeen in a couple of hours and arrive at specially-built airports.

He also told the crowd that aircraft could be used both for commercial and military purposes and offered some eerily prophetic words about the deployment of planes to “drop dynamite” on the enemy during conflict.

Fewer than 20 years later, this duly happened during the First World War.

The Birdman of Inchmarlo

The Evening Express carried a tribute to Fleein’ Geordie, who died in 1939 aged 80, which told how he was fascinated by flight and dreamed of the day when people would be transported by “aerial locomotion” between continents.

It said: “His early experiments involved a number of model gliders and the Victorian photographer Andrew Turner of Banchory took studies of the inventor with the machine in the garden of his home in Inchmarlo (which are now in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh).

“A contemporary aeronautical magazine carried a photo of Davidson’s model in flight, but there was no conclusive evidence of his larger flying machine, said to be operated by ‘rowing as in a boat’, ever being in the air.

“Fleein’ Geordie is supposed to have taken it for a ‘hop’ in a field at Inchmarlo in the summer of 1897, but the experiment ended when the machine crashed into a tree.

“He presented a paper, The Flying Machine of the Future, to the Royal Aeronautical Society and visualised the day when a person would fly from city to city, such as London to Paris, have lunch on board the craft, attend to business in France and then be back in London in time for dinner.

“He envisaged landing stages, resembling enormous platforms, being erected to handle these flights which would be made on a regular basis. And he delighted his audience by producing a model of one such platform.”

Fleein’ Geordie was no idle daydreamer. He later designed a direct-lift air-car based on the model glider flown at Inchmarlo.

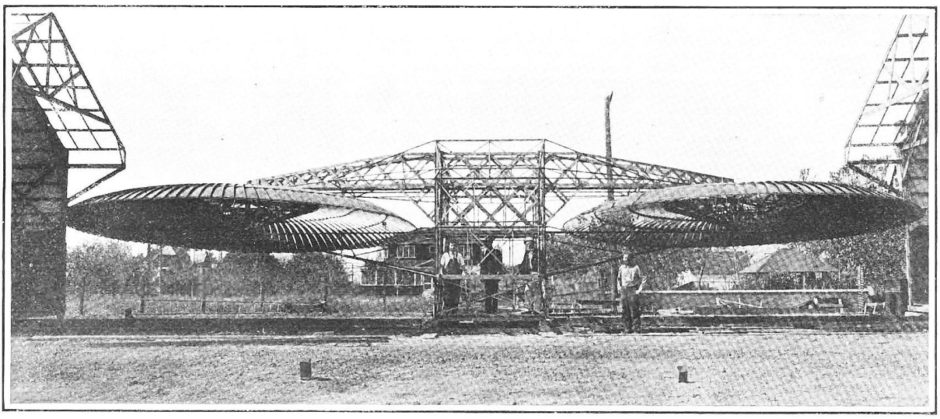

“The strange machine had a wing span of 100 feet, seated 20 passengers in an enclosed cabin and was powered by two Stanley steam engines. The upward thrust came from two rotary lifters, which were called “gyropters”.

“And in theory, it was an early helicopter. He later worked on a new version at Montclair in Colorado in the USA, and the three-ton prototype was tested satisfactorily enough for experiments to continue.”

He defiantly returned to Inchmarlo

This fellow Davidson was never deflated by setbacks or adversity. If one project didn’t work, he rolled up his sleeves and started again.

After celebrating the success of the Wright brothers, Orville and Wilbur, in bringing manned flight to fruition in 1903, he revived the idea of a monoplane in 1906 with another patent being taken out to preserve the new design.

Early in the year, the initiative to develop the craft which had been renamed as a gyrocopter was moved to the United States.

But again, following an unsatisfactory test of the centre section after its construction near Denver, this design was also abandoned and he returned to his roots in Scotland.

Thereafter, despite several other attempts to build another machine, Davidson eventually had to admit defeat due to lack of support and money and retired, albeit reluctantly, to his cherished Inchmarlo.

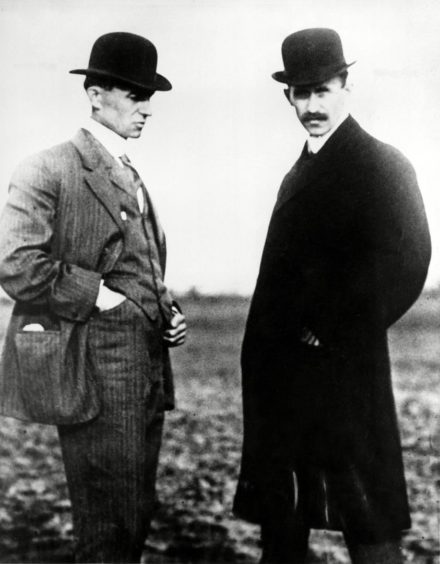

He was regarded as an impressive, if imposing character, and locals saw him striding through Banchory in a long cape and balmoral, sporting a waxed moustache. He died in 1939 and is buried in the village cemetery.

Duncan has studied flying innovators

Historian and author Duncan Harley, who is working on a new book, Long Shadows – Tales of Scotland’s North East, has investigated the part played by the region in the development of aeronautics.

And he included Fleein’ Geordie among several far-sighted figures who stamped their imprint on something we all now take for granted.

He said: “Scottish aviation history is full of stories of brave pioneers who pushed the boundaries and set records for others to break.

“July 1914 saw Norwegian flyer and sometime Antarctic explorer Tryggve Gran set the record for the longest-ever flight over water when he flew from Cruden Bay to Stavanger in Norway.

“His record stood until post-war 1919 when Alcock and Brown made the first non-stop transatlantic flight from Europe to the United States.

Huntly had its own pioneering hero

“The town of Huntly had an early brush with aviation in August 1910 when aviation pioneer Douglas Gilmour took off from the town’s Castle Park.

“Owner of an early French-built Bleriot monoplane, Gilmour had a keen nose for publicity and was a favourite with the press, having gained national notoriety by bombing the submarine depot at Portsmouth with oranges, much to the embarrassment of the Navy.

“Although the Huntly flight ended safely – the plane having landed in a field near the town’s East Park Street – Gilmour was killed two years later in 1912, when his aircraft suffered structural failure over Richmond.

Geordie was spared the blitz

“Then there is Banchory’s eccentric inventor Fleein’ Geordie, a pioneer Scottish aviator and designer of the steam-driven Davidson air-car.

“Born in 1858, the fourth son of the Laird of Inchmarlo, he was one of many early aviation pioneers who in the years prior to the Wright Brothers’ successful 1903 manned flight experimented, at some personal risk, with heavier than air flying machines.

“Weighing in at almost eight tons, his air-car concept was certainly ambitious. Between 1883 and 1897, he carried out local testing of early and simpler monoplane designs culminating in a well-publicised flight attempt in Banchory’s Burnett Park.

“In front of assembled press and curious onlookers, he took off in a scaled-down model of his monoplane, only to crash almost immediately.

“Unhurt, he continued to develop his theory that if birds could fly, man should surely be able to do likewise.

“He died at Inchmarlo Cottage in Banchory and lived to see his predictions that aeroplanes would fly across the Atlantic and be used to ‘drop dynamite on our enemies’ come true.”

The Scot was a dreamer who came close to making history and foresaw the possibility of air travel.

But at least he was spared the sight of the blitz that rained down on Britain just a few months after his death.

See more like this: