He worked with budgets that could only aspire to shoestring status and forced him to buy pies and rolls from the bakery to feed his youthful cast.

Yet there is one quintessential ingredient Bill Forsyth which lent to a small, select number of Scottish films in the 1980s: That Sinking Feeling, Gregory’s Girl, Comfort and Joy and, of course, Local Hero. And that is humanity.

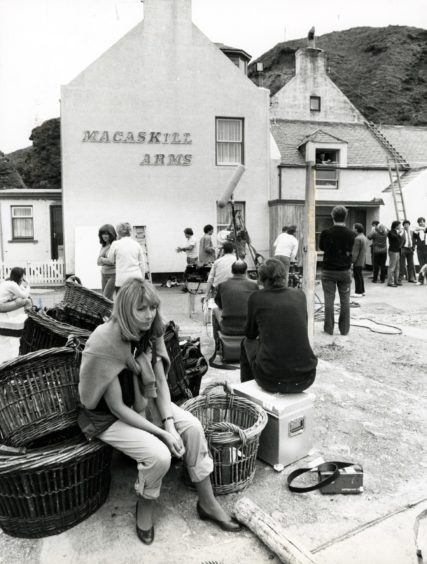

The latter work, which was shot in and around the coastal communities of Pennan in Aberdeenshire and Morar in the Highlands, was the first cinematic production to grapple with the impact of the oil boom that transformed Scotland in the mid-1970s.

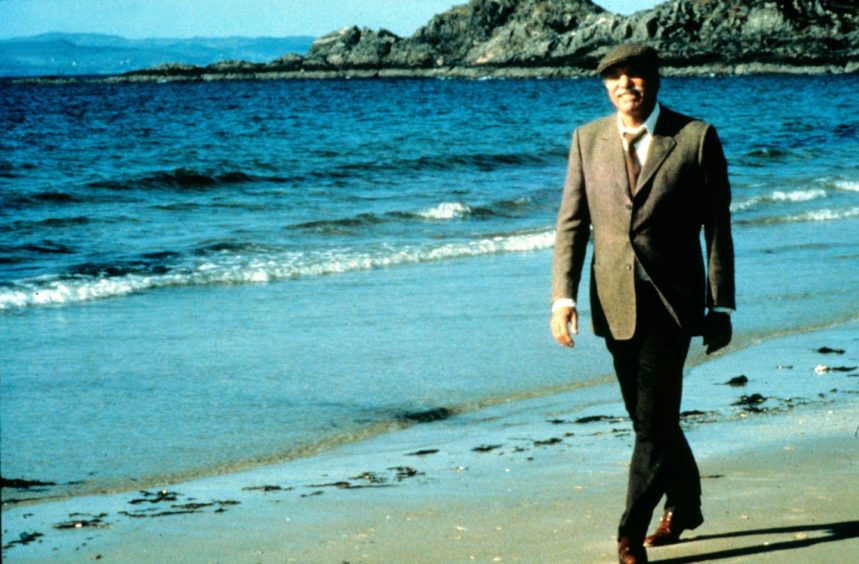

And it was also the first of Forsyth’s films to feature an A-list Hollywood star in Burt Lancaster, who had previously excelled in such diverse offerings as From Here To Eternity, Sweet Smell of Success, The Birdman Of Alcatraz, Gunfight At The O.K Corral, Elmer Gantry, The Leopard and Judgment At Nuremberg.

As somebody who had visited the Findhorn Foundation in Moray – and even helped in the construction of the Community Hall – Lancaster was already familiar with the rugged coastlines and dramatic scenery that abound in Scotland.

And, according to Local Hero’s associate producer, Iain Smith, he didn’t require a second invitation to accept the role after reading Forsyth’s script.

It was the cherry on the parfait of a movie that has become a cult classic.

Forsyth, 76, had previously demonstrated his ability to draw and depict gangly adolescence with honesty and humour in Gregory’s Girl.

Fellow writer and director, Jon S Baird, was among its many aficionados while he was growing up in Peterhead in the late 1970s and 1980s and said: “It was a huge film for my generation and I think it is one of the most quotable pieces of Scottish culture.”

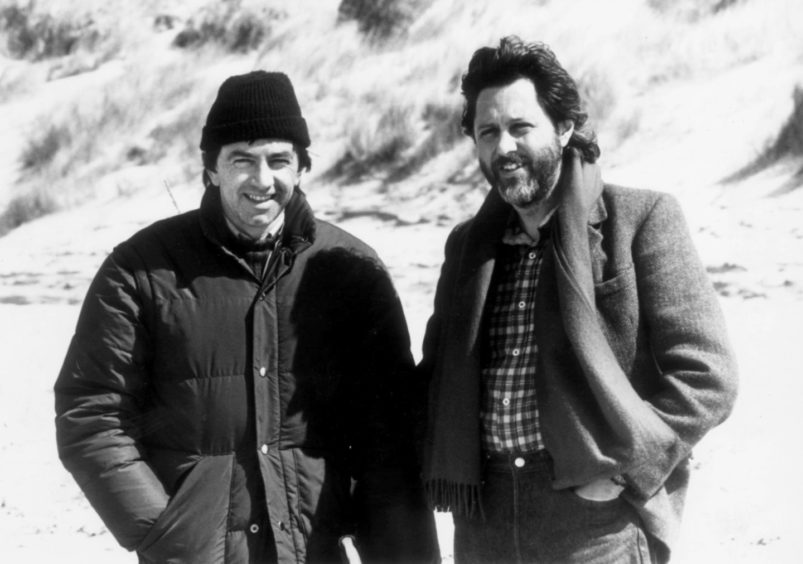

But, by the time he joined forces with David Puttnam, the Oscar-winning director of Chariots of Fire, Forsyth had his eyes on a more ambitious project: one that combined hard economic reality with the culture clash between American industrialists and local Scottish residents and natural phenomena such as the Northern Lights.

Bill always avoided stereotypes

As Smith told me: “It would have been easy for Local Hero to have turned into a modern twist on Whisky Galore, but Bill didn’t want to take the obvious route and that is one of the things which has defined his career.

“I know that he grew frustrated with having so little money to make the early films, but he managed to find ways to circumvent the problems and created three-dimensional characters whom you could really believe in and get behind.

“He didn’t want the Americans to be portrayed as the brash, greedy guys and the Scots as the plucky underdogs in Local Hero and actually turned that on its head in the script.

“He has never been interested in resorting to stereotypes and that is one of the reasons why these characters still have resonance now, 30 or 40 years later.

“It teaches us lessons as film-makers, that you can do all the visual effects and special effects that you like but, at the end of the day, people want to watch people.”

In the last four decades since Smith’s involvement in a movie he still regards as a masterpiece, the Scot has brought his talents to bear on a string of international films, including everything from The Mission to Mad Max and Planet of the Apes to Luc Besson’s sci-fi caper The Fifth Element and Seven Years In Tibet with Brad Pitt.

Yet he has never relinquished his love for the story of the billion-dollar Houston oil firm that originally plans to build an enormous, environmentally destructive oil refinery on the site of Ferness – the fictional version of Pennan – but whose executives are gradually captivated by the new landscape in which they find themselves.

It’s one of those rare ventures where everything clicks: the haunting score by Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits, the chemistry between a vibrant cast of Scottish actors, including Peter Capaldi, Denis Lawson, Alex Norton, Rikki Fulton, John Gordon Sinclair and Fulton Mackay and the performances of their American counterparts, led by Peter Riegert – in a role that was sought by Michael Douglas – and the ageing, but hugely affecting presence of the maestro Lancaster.

And the scenery, of course, never disappoints, from the ethereal beauty of the Aurora Borealis illuminating the North Sea to the sweeping, majestic white sands of Morar and a red phone box that became a postcard view and still remains intact today.

The making of the film in the spring of 1982 allowed the extras time to mingle and appear on screen with present and future luminaries of stage and screen and, as Smith recalls, this wasn’t a production dogged by difficulties, egos or personality clashes.

Forsyth, after all, had previously worked with several of the cast and, befitting his reputation as a collaborative spirit rather than a look-at-me prima donna, savoured the scenes where he and his colleagues were able to capitalise on the north-east setting.

Smith said: “Bill never followed a conventional path and the scene at the end where Riegert’s character, back in the United States, empties his pockets of shells, and realises that he was happier when he was in Scotland, packs a real emotional punch, but there is no sense of the film laying the message on with a trowel. Quite the opposite.

“Another reason why it has lasted so well is that audiences still love to watch real human humour and storytelling.

“There’s a particular West Highland thing that Bill captured, which is telling the straight-faced joke and it works beautifully.”

Local Hero with The Fonz, anyone?

Puttman and Forsyth had gained international lustre, culminating in the Oscar-winning success of Chariots of Fire and the quirky universal appeal of Gregory’s Girl, so it wasn’t a surprise when they joined forces to bring Local Hero to fruition.

With Warner Brothers bankrolling the venture and a litany of well-known faces keen to be involved with it, country singer Willie Nelson was among the contenders for the part that eventually went to Lancaster, while Henry Winkler (who played The Fonz in Happy Days) was another actor whose name was linked with the movie.

However, although there were hopes that it might be the start of a series of collaborations or spin-offs between the producer and director, Forsyth made it clear he wasn’t interested in being absorbed by any studio system or re-treading old ground.

It has meant that his output has been limited in the last 30 years but his confrere, Smith, believes that single-minded philosophy is one of his most striking assets.

He said: “Bill’s a one-off, he is a true original and he has always blazed his own trail. He set off to write something out of the ordinary where the romantic ones in the world were the big oil companies and those who were out for the pennies were the villagers – and that is one of the things which makes it funny.

“I still have so many good memories from that time. It was a very happy cast and a very happy production with a relatively trouble-free shoot, and that sense of lightness and freshness came out in the film. There was no in-fighting or tension on set.

“The early reviews from the critics weren’t all that positive but the public soon showed their appreciation and the fact we are still enjoying it now, in 2021, tells its own story.

“At the time, David thought that Bill could go and make other films in the same genre, but Bill made it clear he wasn’t going to play that game.

“I even suggested to him that there could be a TV spin-off, but he killed that idea stone dead and, with hindsight, I can understand why.

“It comes down to honesty and credibility and, for Bill, he had told his story and it was time to move on to something else.

“I have no doubt that it was every bit as enjoyable an experience for Bill as everybody else in the cast and crew, but he had finished the job.”

Film critic Mark Kermode regards Local Hero as Forsyth’s masterpiece and, in 2008, he and the director returned to Pennan for a poignant reunion with the community.

The camera-shy Scot recalled: “We had to find a location for the village before the weekend and it was Friday, about 2pm, so they more or less said I had to pick this place or the whole thing (filming schedule) was out of whack.

“There was no way I could say no but fortunately it was magic and it worked.”

Forsyth even sat down and watched the movie for the first time in nearly a quarter of a century and, ever the perfectionist, couldn’t quite make it through to the end.

But audiences everywhere have revelled in this mesmerising creation from one of the most idiosyncratic talents in the history of cinema.