There’s a gap in Castle Street, Inverness where no. 53 should be – and it seems to symbolize a gap in the collective memory where one of the city’s most famous and successful daughters should be.

The old building at no. 53 was the site of a well-respected fruit shop owned by Colin MacKintosh in the 1920s, tenanted out in flats above.

Due to the building’s parlous state of repair it was pulled down earlier this year, set to rise again as new flats with retail below, complete with its original stonework and façade.

Colin was proud of his shop and his prosperous business, but the dark horse in this tale is his daughter – birth name Elizabeth, but aka authors Gordon Daviot, Josphine Tey, and, as recently revealed by her biographer, F. Craigie Howe.

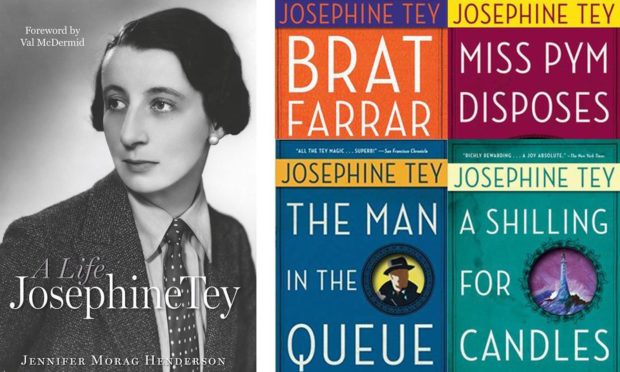

Gordon Daviot was a feted author and playwright, a household name, courted by Hollywood; Josephine Tey was considered ‘the crime writer’s crimewriter’ and F. Craigie House may well have become a household name if Elizabeth ‘Beth’ MacKintosh had survived beyond her 57th year.

Interpreting this mix of personas all inside one modest Invernessian is hard for people on the outside, but not at all for Beth.

She compartmentalised her talent and her multiple personas so successfully, and so completely failed to promote herself that perhaps this is the reason why she is no longer a household name, despite never having been out of print in 80 years.

It’s hard to over-state how famous and important Beth’s work was in the 30s and 40s.

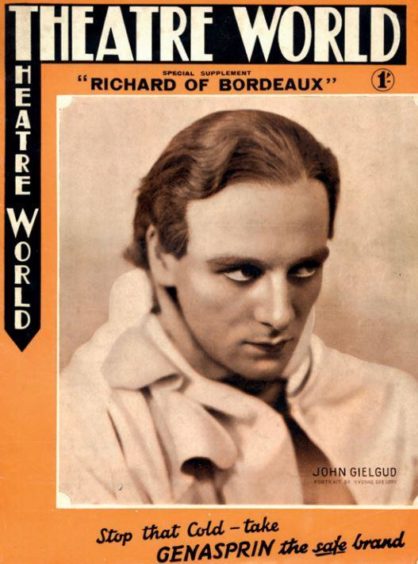

As Gordon Daviot, her 1932 play Richard of Bordeaux packed out the West End, with John Gielgud, Beth’s choice, in the title role. The role effectively launched Gielgud to stardom. It was performed by schools and amateur dramatic societies across the land for decades.

This dramatic success saw Beth mingling with the glitterati of the London scene, including Laurence Olivier – and yet she refused to buy permanently into that world, retreating instead to Inverness to carry on writing.

As Jospehine Tey, her 1936 novel, A Shilling for Candles, attracted the attention of Alfred Hitchcock who adapted it into the film Young and Innocent a year later.

She was courted by Hollywood, writing for James Stewart in Next Time We Love, a big hit in 1936- but kept her feet firmly on Highland ground.

Her crime writing was seen in the same league as Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Dorothy L Sayers and Margery Allingham – but Beth kept herself aloof, retreating from the limelight to Inverness to carry on writing, and refusing to give press interviews.

And although she was a proud Highlander, Beth had a growing love of England, to the extent that she left the bulk of her estate to the English National Trust.

She refused to espouse the growing nationalist movement of the time, unlike her direct contemporary Neil Gunn.

She kept apart from the Inverness social scene, preferring long solitary rambles instead.

Perhaps those are more reasons why Beth MacKintosh is somehow airbrushed out of glory in her own country.

Beth was the eldest of three daughters, her father Colin a Gaelic speaker from Applecross who uprooted to Inverness to establish himself as a highly successful fruiterer.

Her mother Josephine had roots in Aberdeenshire, Perthshire and England.

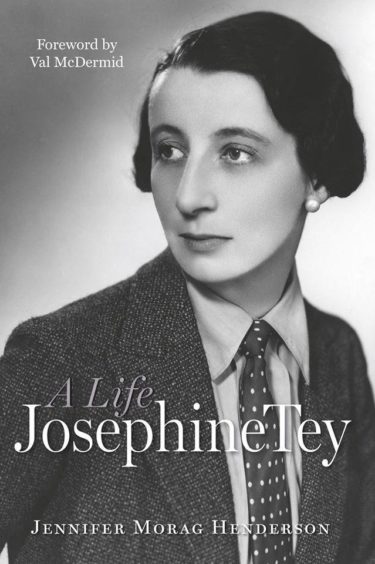

Henderson has left no stone unturned in ferreting out a great deal about her subject in Josephine Tey: A Life.

Beth attended Inverness Royal Academy, which Henderson thinks she didn’t enjoy, although she won prizes, doing well in art, music, English and French.

She did well enough to be awarded a bursary for her final year at the then fee-paying IRA.

She toyed with the idea of art school, but didn’t make the grade.

However, she excelled in PE and in 1914 attended Anstey Physical Training College in Birmingham.

At one point she taught in an Oban school she didn’t think much of, and sustained an injury when a boom in the gym fell on her face.

In true writerly fashion, she turned this incident into a method of murder in her novel Miss Pym Disposes.

World War One changed life for everyone – in Beth’s case she lost a soldier with whom she had a romantic involvement.

Inverness was a military town, heaving with Cameron Highlanders, and Beth returned to every summer to work as a voluntary aid detachment nurse, possibly in Leys Castle Auxiliary Hospital.

Given the times, it was hardly surprising that she fell in love with a soldier but she is so secretive about this relationship that even her biographer has had to make well-researched guesses as to the identity of the young man.

Henderson thinks it was either the dashing Gordon Barber of the 1st Camerons, who died in the Somme in 1916, or the 4th Cameron officer Alfred Trevanion Powell from London who died at Vimy Ridge in 1916.

True to form, Beth’s war romance and heartbreak ultimately remains a mystery.

Perhaps Gordon has the edge, with Beth borrowing his name and combining it with Daviot, a favourite family holiday retreat, to create her first pen name.

In 1923, Beth’s mother took ill, and she returned to Inverness to help nurse her.

Josephine’s death was a catalyst for two important changes in her life.

She started writing as Gordon Daviot, and as the eldest daughter, she returned permanently to Inverness to take on the role of keeping house for her father.

Beth tackled historical and religious themes, writing around a dozen one act plays, and as many full length ones, but apart from Richard of Bordeaux, none achieved enduring success.

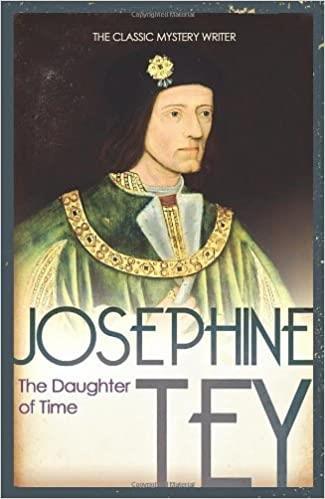

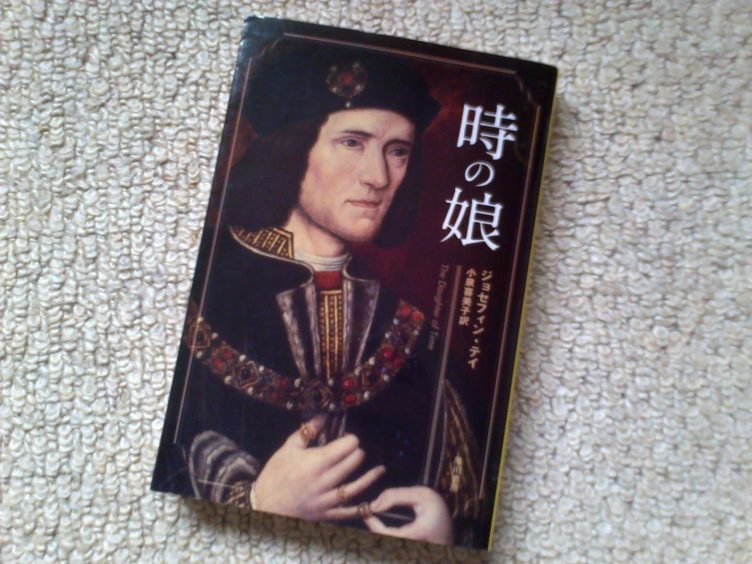

As Josephine Tey (taking two names from her mother’s side) Beth’s last published novel, her 1951 ‘The Daughter of Time’ was was voted number one in The Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time list compiled by the British Crime Writers’ Association in 1990.

In 1995 it was voted number four in The Top 100 Mystery Novels of All Time list compiled by the Mystery Writers of America.

In it her detective character Alan Grant of Scotland Yard becomes intrigued by a portrait of King Richard III, which he thinks shows a gentle, wise man, rather than a cruel murderer.

He goes on to the conclusion that the claim of Richard being a murderer is a fabrication of Tudor propaganda, as is the popular image of the King as a monstrous hunchback.

Henderson calls it “the kind of book you lend to people and don’t get back.”

The work was rediscovered by many readers after Richard’s body was found buried beneath a car park in Leicester.

Perhaps celebrated crime writer Val McDermid sums up Tey’s enduring appeal to the crime fiction fraternity.

She writes in her foreword to Jennifer Morag Henderson’s biography: “I can still remember the excitement of my first encounter with Josephine Tey more than forty years ago. It was a battered, second hand paperback of Miss Pym Disposes. I hadn’t read a crime novel like this before. It was the opposite of formulaic; it explored relationships and character in a nuanced way that made it feel much more modern than most of the other genre novels I’d read.”

‘The opposite of formulaic’ – perhaps that also sums up the uniqueness of Beth as a person.

Henderson says: “For me, Josephine Tey, Gordon Daviot and Elizabeth MacKintosh are an inspiration, not just because their writing has brought me hours of enjoyment, but because the story of Elizabeth’s life showed me a new version of what was possible for a Highland woman.

“Her family came from a background of crofting and domestic service, and through hard work and a belief in education supported their daughters and encouraged them to aim high.

“Elizabeth went from Inverness Royal Academy to London’s West End, to Broadway, to Hollywood- and back again, to the small town of Inverness.”

Researching the biography and giving talks about Josphine Tey have revealed the reverence in which Tey’s fans hold her.

“A reader said that The Daughter of Time was possibly the most important book ever written…then he took out the qualifier. The Daughter of Time, he said, was simply the most important book he had ever read.”

On another occasion, Henderson was presented with a photo of a Japanese copy of The daughter of time which a Japanese fan presented to her when she was giving a talk on Tey at the British Library.

“This man was a crime writer, he had come to London specifically for the talks, and had been particularly influence by Tey, so was delighted to hear more about her real life.”

Beth died in 1952 of cancer, some six months after the death of her father.

She was at the height of her powers, staging one play at the Citizen’s Theatre and writing another one under her third penname, F. Craigie Howe- it wouldn’t do to have a whole season’s plays written by the same writer, it was felt.

“Sadly Beth is not remembered by any gravestone or marker in her home town. But her books are in every bookshop, and on many shelves in many homes,” writes Jennifer Morag Henderson.

Shouldn’t she have a blue plaque? How about Castle Street?

Henderson says: “There is a gentleman in England who I’m in touch with who’s put in a considerable amount of work trying to get a blue plaque for Josephine Tey.

“He’s a member of the Richard III Society, and came to Josephine Tey’s writing through The Daughter of Time.

“He had most success with the address in London where she died, but has also spent some time searching for a suitable site in Inverness.

“Unfortunately he hasn’t been able yet to identify a good site in Inverness or attract the relevant interest – but certainly the Castle Street site could be a good location for some sort of plaque.”