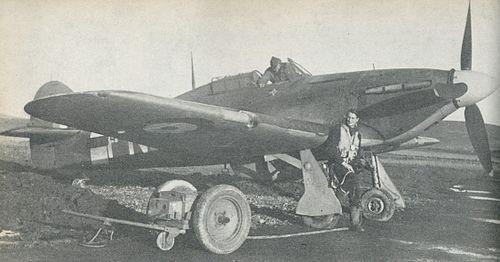

On August 27 1941, sixteen Hurricane pilots from 331 Squadron were training in the skies above Caithness.

They were practising flying in V formation, but as they attempted a 180 degree turn to the right, something went badly wrong.

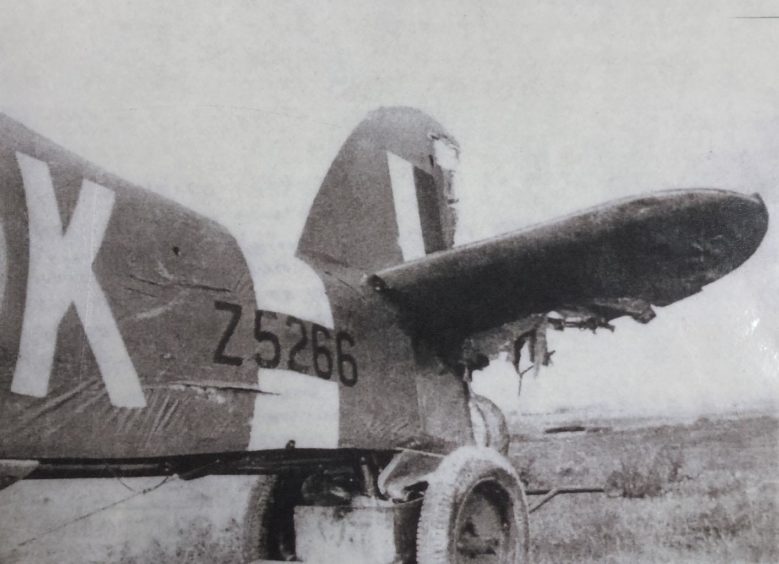

Two aircraft collided, one went headfirst into the peat and burst into flames, while the other managed to limp back to base at RAF Castletown.

The pilot of the plane which dived into the peat escaped by parachute, while the other pilot, now without a tail rudder, managed to land successfully but unable to steer, crashed straight into a Spitfire undergoing maintenance, hurling the engineer to the ground.

No-one was injured, and training accidents weren’t infrequent during the war, often with far worse results.

Fast forward several decades

Halkirk neighbours Lewis Sinclair, and Robert Falconer had always been aware of a slight hollow in the peatland of the Causeymire and had heard it was the site of a WW2 plane crash.

Almost 50 years after the incident, the two men took it upon themselves to excavate what was left of the bog-bound plane, from its soggy resting place- and they ended up with far more than they bargained for.

To get permission to excavate the plane- which at the time they believed to be a Spitfire-they had first to find out the pilot’s name, the type of aircraft and its number, and the date of the incident.

This proved the first of many challenges, but through a connected friend, they found out the report of 331 Squadron that day.

Hitting the jackpot

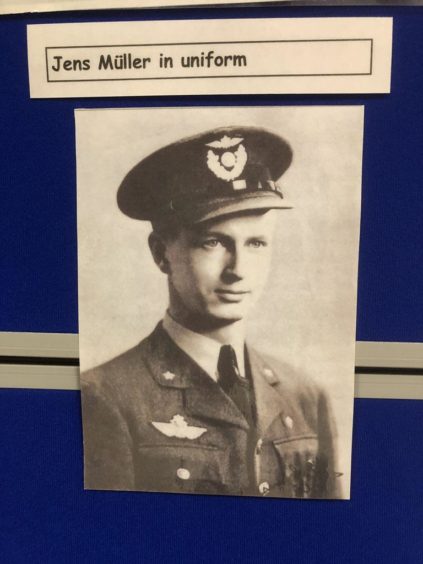

And what turned the quest from relatively mundane into a jackpot is the identity of the pilot who baled into the bog.

He was 2nd Lt Jens Müller who less than three years later would be one of only three men to make it to safety in the great escape from Stalag Luft III.

331 Squadron RAF was manned by exiled Norwegian aircrew and was part of Fighter Command from 1941 to 1944.

They inherited Hawker Hurricane Mk1s from a Polish RAF unit, which had to be rebuilt before 331 Squadron could become operational on September 15, 1941.

The squadron was to defend northern Scotland, and moved to RAF Castletown on August 21, later going on to RAF Skeabrae in Orkney.

The incident wrote off one plane and ended up damaging two more- but the show must go on.

It didn’t put 24 year old Müller off.

Natural born pilot

He seems to have been a natural born pilot, getting his wings aged 18.

He had quite an exotic background, born in Shanghai to Norwegian engineer Einar Jønsberg Müller and British actress Daisy Constance Russell.

He was studying engineering in Zurich when war broke out and was in England signing up by May 1940.

When 331 Squadron saw active service in 1942, they were based at North Weald, England.

On June 19, Müller’s Spitfire Mark V was shot down by a German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 off the coast of Belgium.

Once again his quick wit saved him and he baled out by parachute, this time with his inflatable dinghy.

It took him almost 3 days, but he managed to paddle ashore- only to be nabbed by a German sentry.

The Great Escape

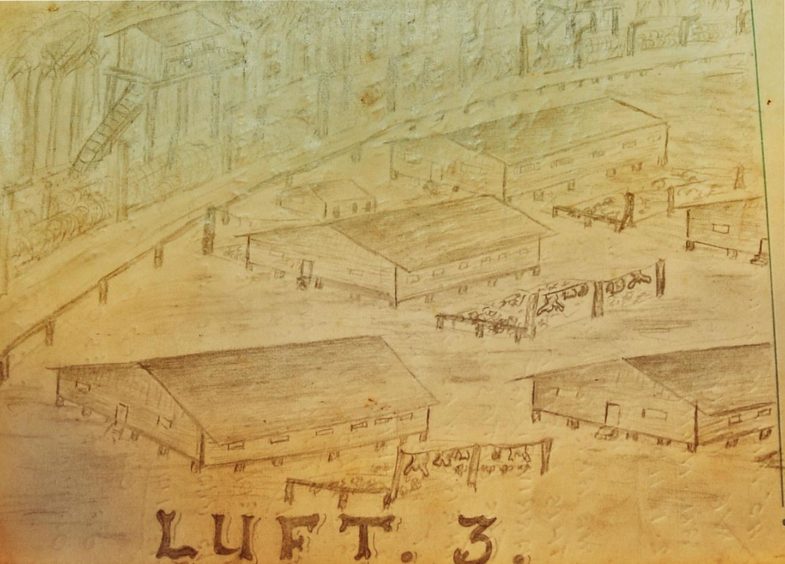

After weeks of tough interrogation, he was transferred to Stalag Luft III in Zagan, Poland to join hundreds of allied forces air force personnel.

The story of The Great Escape is legendary, embroidered for the silver screen, or meticulously recorded elsewhere.

Müller told his own story in The Great Escape from Stalag Luft III: The Memoir of Jens Muller.

With his knowledge of engineering, he designed the bellows that pumped the air into the escape tunnel, scavenging every scrap of canvas he could find for the task.

He was the 43rd prisoner to leave the tunnel, followed by fellow Norwegian Pers Bergland (332 Squadron RAF).

“It took me three minutes to get through the tunnel. Above ground I crawled along holding the rope for several feet: it was tied to a tree. Sergeant Bergsland joined me; we arranged our clothes and walked to the Sagan railway station.

‘Bergsland was wearing a civilian suit he had made for himself from a Royal Marine uniform, with an RAF overcoat slightly altered with brown leather sewn over the buttons. A black RAF tie, no hat.

“He carried a small suitcase which had been sent from Norway. In it were Norwegian toothpaste and soap, sandwiches, and 163 Reichsmarks given to him by the Escape Committee. We caught the 2:04 train to Frankfurt an der Oder.

“Our papers stated we were Norwegian electricians from the Labour camp in Frankfurt working in the vicinity of Sagan.”

Sqn Ldr Roger Bushell masterminded the Great Escape and had arranged for Müller and Bergsland to find one of his contacts in a brothel in Stettin.

They changed the plan when they met a Swede who offered to help them, telling them to wait down at a pier in a harbour- fruitlessly, as it turned out, that ship had sailed.

After a couple of days they met two Swedish sailors who helped smuggle them onto a ship to safety in Gothenburg.

With the help of the British consulate, they were flown to RAF Leuchars.

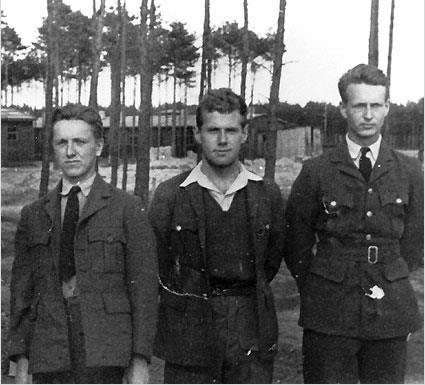

Müller, Bergsland and Bram van der Stok, a Dutch pilot of No. 41 Squadron RAF were the only three of 76 escapees who made it to safety on the night of March 24, 1944.

Caithness man in Stalag Luft III

Fifty of the escapees were shot, including Sandy Gunn, originally from Dunbeath, Caithness, son of a doctor who moved to Aviemore.

Lewis Sinclair had heard more about Sandy Gunn than about Jens Müller before he set about unearthing the plane from the bog.

He said: “We don’t know much about his Caithness origins , although he did write to his mother saying he was feeling so unfit in Stalag Luft III that he could do with a good day’s work at the peats on Rumster hill.”

Sadly Gunn was one of those murdered in the retribution meted out to the prisoners.

Caithness tunnel underway

In 1990, Lewis and Robert began their own tunnelling effort, with Lewis down the ever-deepening hole in waders, digging down inch after inch using nothing more than a 15” grape.

The pair were able to dedicate one day a week to the task.

They had borrowed a pump to drain out the ever-accumulating water, and that’s about as high-tech as it got for almost six months.

Ex-railway man Lewis said: “I didn’t find it hard, I was used to digging on railway metal.

“I would throw bits and pieces of what I found up to the surface and Bobby? Would wash them and we’d try and work out what they were.

“It was strange handling the pilot’s harness when we found that, strange to think he would have been the last person to wear it.”

Live ammunition

Then came the startling discovery of an entire wing, bearing six machine guns complete with rolls of live ammunition.

Lewis said: “Some of the ammunition must have gone off when it crashed, but there was still plenty in rolls in boxes.

“They were in perfect condition, and a couple of the machine guns could easily have been fixed, ready to fire again.

“Bomb disposal came from Lossiemouth and made everything safe, and took the guns and ammunition away.”

Getting the engine out

Extracting the engine from the suction of the bog proved a mighty challenge.

The Rolls Royce Merlin more than half a tonne and was head down in the peat.

Using the salvaged roof of an old van to form a sled and an old grey Fergie to pull, the engine grudgingly made its way to the light for day for the first time in almost half a century.

Lewis said: “It was in very good condition, considering it must have gone in there at around 300mph.”

But within two hours, the gleaming brass on it began to tarnish, and the black paint began to flake off.

Almost devoid of paint now, the engine is a popular exhibit at Castletown Heritage Centre.

Lewis says he’s proud of his achievement, something which would be impossibly expensive to pull off today.

He said: “We only had a pump and an old Fergie. You would need diggers now and crowds of people.

“I’m pleased two of the plane’s suspension legs have gone onto a static Hurricane on display at RAF Duxford.

“A small piece of the of the plane, I’m not sure what, goes up each time in the Battle of Britain memorial flights.

“I think Jens Müller was a very lucky person, to get away with the crash in Caithness, then to be shot down over Belgium, taken prisoner and escape.”

For the rest of the war, Müller was sent to Little Norway in Canada to train fighter pilots.

Afterwards, he had a successful career as a commercial pilot with SAS Scandinavian Airlines.

In his retirement, he spent his time happily making miniature bellows. You can take the boy out of Stalag Luft III…

Lewis and Robert contacted him in 1990 to tell him of their plans to dig up his old aircraft.

He wrote back, describing the incident in detail.

He says: “I was the left wing-man of the outside flight on its way to the inside position and Lt Lundstein was the right wing-man of the inside flight on its ay to the outside position.

“The altitude separation was insufficient and the rudder and elevator of Lundstein’s aircraft hit the propellor of mine.

“Rudder and elevator were cut to about 30% of normal.

“Lundstein’s landing at Castletown was an example of good piloting.

“The propellor of my Hurricane was reduced to stumps and the engine mounting was damaged so the engine pointed some 10 degrees to port.

“The terrain below did not look suitable for a forced landing and I baled out.

“It is hard for me to imaging that there is anything left of that aircraft worthwhile salvaging.”

Look out for our feature about RAF Castletown’s role during the war coming soon online

More like this:

Piece of rare Longside Second World War history found in North Shields

Italian historian discovers Aberdeen war hero’s Spitfire parts in Sicily