Marshall P Cloy sounds like a character from a Western movie.

And there were elements of the same mad dash in the Cromarty Firth in the early 1970s as happened during the Klondike gold rush 75 years earlier.

The arrival of thousands of men and women from all over Britain, the rest of Europe and the United States formed part of an extraordinary story in the Eastern Highlands after the region was chosen as the perfect place to create a vast fabrication yard to construct oil rigs for the newly-discovered Forties Field in the North Sea.

In the years ahead, the population of places such as Alness, Tain and Dingwall increased by as much as 1,000% in the space of a decade, during what some people described as “the greatest engineering project of its time”.

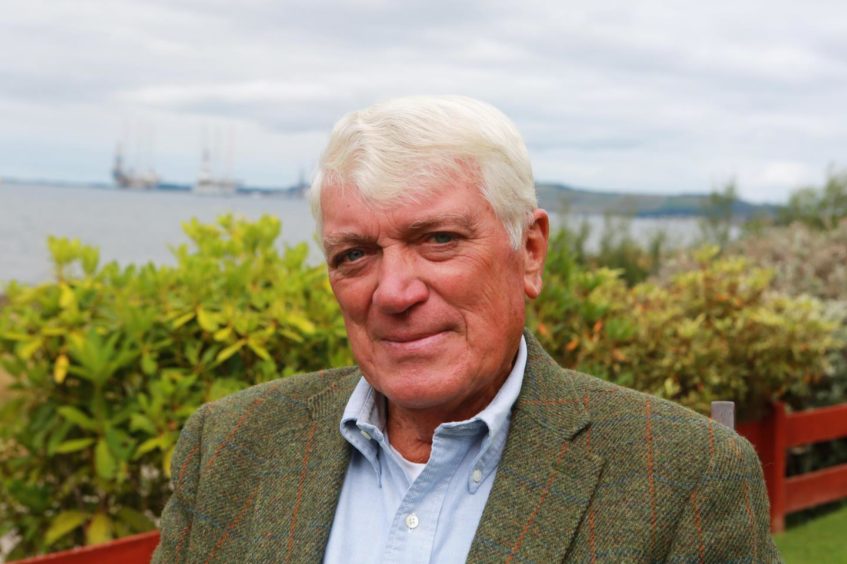

Mr Cloy, the senior vice-president of Brown & Root, was among those who spearheaded the crusade to develop vast installations in a remote part of Scotland.

He said: “I soon realised we were probably going to do something that mankind had never done before. And it became the biggest man-made hole on Earth.”

Margaret Paterson and her late husband, Tommy, had emigrated to Australia in 1968, among the “£10 tourists” who were searching for work Down Under.

But when they heard the news about the opportunities in Nigg, they returned home in the winter of 1972 and discovered a rapid transformation was in progress.

She recalled: “I was washing dishes when Tommy asked me if we could give two lads their supper because they had nowhere to stay that night.

“Well, I always said ‘deal small and serve all’ and I put a few more potatoes in the pan and brought out an extra fish.

“We wanted to help – it was the Highland way.

I don’t think anybody realised how many people were coming to live and work in the area and we just didn’t have enough houses.”

Margaret Paterson

“We enjoyed the meal together and I knew these boys were only here for the night.

“(In the event) they ended up staying with us for two years.”

The whole of the Cromarty Firth was close to being overwhelmed in the process.

New roads, schools, health centres and other vital pieces of infrastructure were required, but the surge in the population meant that hundreds couldn’t find homes.

Mrs Paterson said: “I don’t think anybody realised how many people were coming to live and work in the area and we just didn’t have enough houses.

“It was, quite literally, a case of no room at the inn.”

The pints piled up at the Piggery

Many of the riggers, fabricators and labourers ended up in caravans, others turned Second World War pill boxes into temporary accommodation and 600 men were holed up in a couple of ageing Greek cruise ships that had seen better days.

Unsurprisingly, this provoked tension and outbreaks of violence and, deprived of any proper leisure facilities, many of these mostly young men sought refuge in the bottle, which ensured that sales of beer and whisky soared through the roof – from 400 to 5,000 pints of beer a week – at the local pub, which became known as the “Piggery”.

One of the bar staff said later: “It wasn’t the sort of place you went to for a family meal.”

Yet if fights erupted, enduring friendships were also established between the Scots and the English and many of their American visitors.

As the years passed, sales of cowboy boots and T-bone steaks rocketed and a number of formerly dour Highlanders started sporting extravagant moustaches and resembled Yosemite Sam.

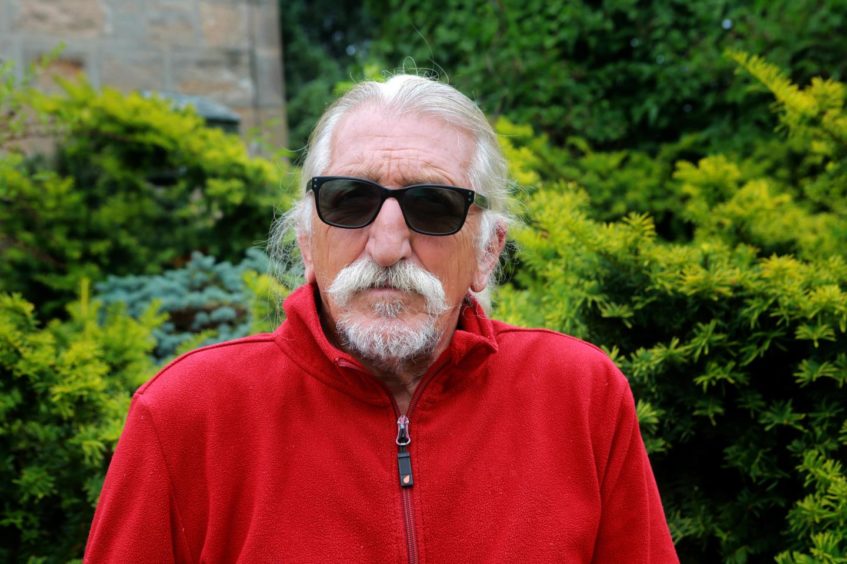

Jackie Mitchell, a fabricator and shop steward in Nigg, spoke about how rich reserves of camaraderie were nurtured in scenes straight out of a pop video.

He said: “I remember one time when we were working inside the ‘cans’ – which is what we called the leg sections of the rigs – and suddenly, somebody started singing Uptown Girl by Billy Joel (which was a massive hit for the American singer in 1983).

“Then, before you knew it, the whole lot of us were singing it and the sound was echoing up through all the different cans – it was like we were in a recording studio.”

The vast majority of the workforce were men in what was often a testosterone-filled environment, but there were opportunities for women such as Heather Mackay to prove she had the right stuff after applying for a position.

And she grabbed it with both hands.

She said: “I remember the very first day, we went up to see if there were any jobs available.

“It was myself and my friend and we weren’t dressed for work, but we were keen and an American guy interviewed us and said: ‘You can start as general workers’.

“Quickly enough, we became welders and I think women welders were better than the men: they were neater, maybe their hand was steadier and I think women are very particular when they do a job to get it right. I’m not saying men aren’t but…”

Ms Mackay certainly impressed her colleagues, but she, just like the rest, were regularly exposed to hazards in a climate where health and safety regulations were non-existent.

That led to one especially hair-raising incident.

Elsewhere on the Cromarty Firth, even as vast structures were being built, the personnel went about their business high in the sky without wearing a harness.

The welders, meanwhile, were used to dealing with hot temperatures, but Ms Mackay had to grapple with something worse, which she recounts as if it was just a minor glitch.

She said: “We were welding inside this massive pipe and working above our heads so the sparks were flying everywhere and a few of them went down my suede jacket.

“You were given these big, dirty suede coats and gloves, so you didn’t get burned, but the next thing I knew, I could smell burning and, when I looked, my hair was on fire.

“Obviously, it was concerning, but I managed to put it out quite quickly. I had funny-looking hair for the next few days!”

Even now, there is something mesmerising about watching the meticulous fashion in which the steel behemoths were installed in the North Sea.

Nobody was absolutely sure the process would succeed, and the relief etched on the faces of all the workforce was evident when the first rig was safely berthed.

Even at that stage, in 1975, there were arguments about who should reap the harvest from the energy dividend and the black seam in the Forties Field.

The Rigs of Nigg, a new BBC documentary to air on BBC Scotland on Tuesday August 17 at 10pm, highlights the political row that erupted as the scale of the development became clear.

Some people thought that the oil bonanza should be used to benefit the whole of the UK but others argued that it was Scotland’s oil.

Half a century later, that debate is still raging, but while the men and women who worked in the Cromarty Firth enjoyed short-term gain, which allowed many of them to invest in new houses, fridge freezers, fast cars and such “mod cons” as dishwashers and microwaves, an increasingly cold wind blew over the region as the 20th Century ended and the Firth became a vast parking lot for redundant rigs.

One of the young lads was offered a bonus back in the early ’70s and when his mates asked him what he planned to do with it, he replied: “I’m going to spend half of it on drink – and squander the rest.”