If one of its principal architects had had his way, Inverness could have looked like a Paris of the north, and its cathedral more like Notre Dame.

How about Boulevard Queensgate, or Boulevard Union?

The influences are clearly there, even though the characteristic proportions and symmetry aren’t always easy to spot at ground level.

Inverness as the Paris of the north isn’t fantasy, but the reality infusing architect Alexander Ross’s plans for the substantial section of the city he was tasked with building in the 1860s.

Ross was heavily influenced by what was going on in Paris at the time, visiting the city in the early 1860s when it was undergoing a major transformation, including the restoration of Notre Dame and the construction of Haussman’s wide, sweeping boulevards.

Contemporary Inverness architect Calum Maclean is researching and writing the definitive tome on Alexander Ross, Alexander Ross, Architect of the Highlands, due for release next year.

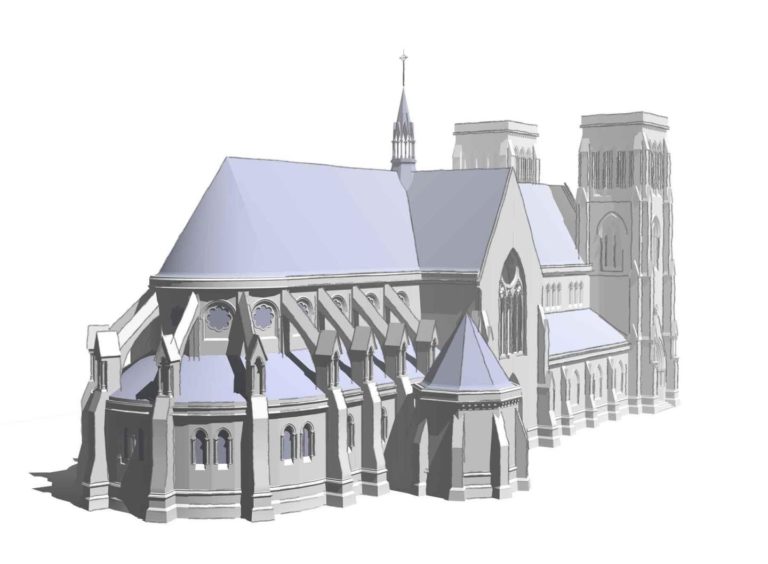

He can shed light on what was going on in Ross’s mind at the time, with his plans for a much more ornate St Andrew’s cathedral than we see now, and the undeniably Parisian aspect of some of Inverness’s central streets.

He said: “Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was in the middle of the restoration of Notre Dame Cathedral and publishing his account of the archaeological investigation and restoration in great detail.

“While in Paris, Ross would have taken a great deal of interest in the cathedral as only a couple of years earlier, in 1859, Viollet-le-Duc had completed the stunning flèche that rose above the crossing of Notre Dame de Paris.

“At the same time Georges-Eugène Haussmann was constructing the grand boulevards for Napoleon III.

“Ross was recreating Inverness as this modern, cosmopolitan and European city, looking to the future with confidence.

“His outlook was very different to that of other famous architects of the time that were pushing the Scottish baronial style and its romantic view of feuding clans and uprisings.”

When it came to Ross’s designs for the cathedral, it’s important to understand the wider context of how it took shape in his mind.

Calum said: “When he was awarded the commission to design St Andrews Cathedral in Inverness he understood that this would be the first cathedral to be built in Scotland since the reformation in the 1500s, and the importance and symbolism of this was not lost on him.

“It started him on a lifelong journey to study and research into the history and origins of Scottish architecture.

“During the medieval period, when the last cathedrals were built, Scotland maintained a strong relationship with France to defend itself from England, creating the Auld Alliance.

“This relationship resulted in Scottish cathedrals having many French details and a character that contrasted with those of England.

“This is most evident perhaps in the use of a flèche, a tall slender, light tower above the crossing of the cathedral, and the use of an apse, the semi-circular end to the church that wraps around the alter, bathing it in light.

“These would become defining features in the Ross’s design for St Andrew’s Cathedral.”

The orginal flèche was removed in the 1960s for safety reasons, and the current green metal cross is irksome to Calum’s eye.

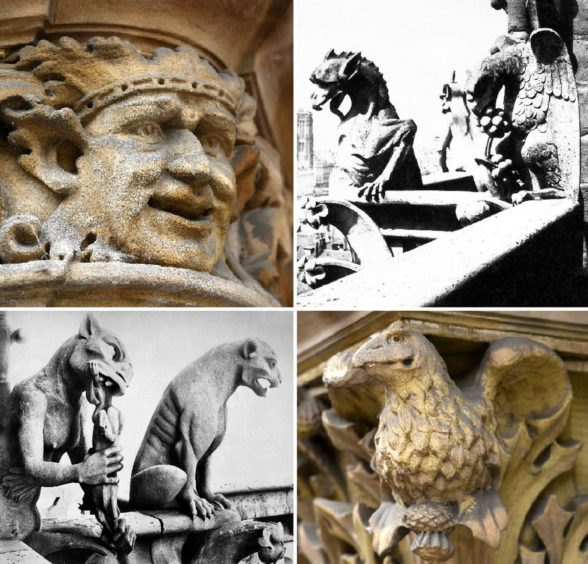

Like Viollet-le-Duc, Ross enjoyed placing symbolic figures on his buildings.

These could be symbolic of what went on in the building, like fire and water at the Rose Street foundry, or for fun and entertainment, like the faces and birds carved just above head level on Queensgate.

Many other features have had to be removed for safety reasons, watering down the Ross vision.

But Calum was recently cheered to see that concrete blocking over the balconies of the nearby Ross-designed Columba hotel has been removed, revealing the original railings as envisaged by Ross.

He said: “The re-emergence of the decorative ironwork balcony and brackets at the Columba Hotel after being concealed in concrete for the last 60 years is a cause for celebration.

“They are rusty and in need of a little TLC, but they have already transformed the look of the building.

“When fully restored, they will be stunning, they will lift the building and they will lift the appearance of the street.”

Uncovering a little more French ‘je ne sais quoi’ for the Highland capital wouldn’t go amiss, Calum says.

“Just think what could happen if this was repeated across the city. ”

He views Queensgate as Ross’s tour-de-force.

Ross took it on for one of his great patrons, Aeneas Mackintosh, with blocks of buildings designed like nowhere else in the Highlands, including French windows opening onto balconies.

Calum said: “The deep arcaded ground floor broke the barriers between inside and out, allowing the life of the street to flow in and out of the building, the first floor apartments were given decorative iron balconies and French doors that opened to allow the street life into the building.

“It was a far cry from the solid walls of masonry and sash and case windows that had been the norm.

“The impact of Queensgate has sadly been diminished by the demolition of the beautiful old Post Office building in the centre of the development and the construction of the modern post office block in 1960s.”

People may know lots of Ross buildings, but there’s no wider grasp of his massive contribution, and people may not yet feel a need to protect his legacy.”

Calum Maclean

The visual character of the wider Highlands also has much to thank Ross for.

He designed 1,000 buildings, and more than 50 churches, and more than 100 schools.

Many of the buildings are small in scale, like steadings, and undocumented.

Calum says on a trip to the Morvern peninsula to look at Ardtornish House he did a double-take as he passed a farm steading at the side of the road.

He jumped out to have a closer look.

“I was sure it was a Ross building. It was noticeably higher quality than the normal farm building.

“I did some research and, sure enough, it was by Alexander Ross.”

Eroding legacy

But Calum is concerned that as time and the elements take their toll on Ross’s Inverness and Highland buildings, his admirers risk taking his legacy for granted.

The need to record the bigger picture with a view to preserving Ross’s legacy is what’s driving his comprehensive and heavily illustrated forthcoming book.

“People may know lots of Ross buildings, but there’s no wider grasp of his massive contribution, and people may not yet feel a need to protect his legacy.

“But they will all be lost, one by one if we’re not careful.”

Calum went on: “Throughout his career Ross pursued the elusive goal of lightness and delicacy in his buildings.

“He uses finials and ironwork, gables and chimneys to break up the silhouette of his buildings.

“Sadly, much of this detail has been lost over time, the impact of weather and lack of maintenance has resulted in many of them being removed.

“While the overall quality of his work remains, it has lost its shine and brilliance. It is like an old classic car, tarnished and rusty, waiting to be rediscovered and brought back to life. “