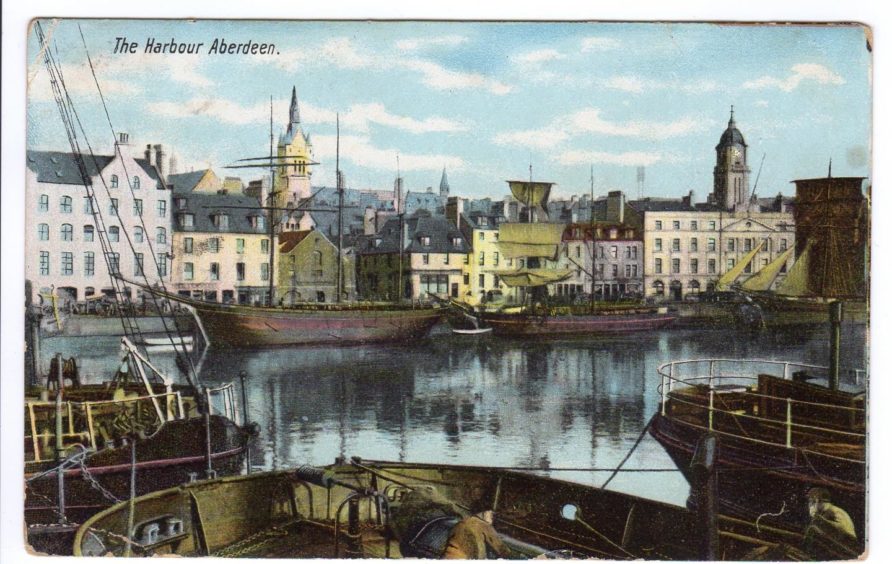

They were the Aberdeen sailors who headed off into the great blue yonder – and found themselves trapped in a hostile country for many years.

The SS Rubislaw was accustomed to making regular trips to Hamburg and there was no indication that anything was out of the ordinary when its 18-man crew – with nine other passengers on board – departed the Granite City on July 31 1914.

But the date is the giveaway in this story. Because, when Britain declared war on Germany less than a week later, on August 4, many Scots missed the last opportunity to flee the country and escape confinement before its borders closed.

And among those who became the enemy overnight were the Rubislaw sailors, many of whom spent the duration of the First World War in a prisoner of war camp, interred alongside around 4,500 or so other unfortunate souls in the heart of Germany.

They were a mixture of teenage seamen such as Fred Bryce and James Shepherd, both aged 17, and more experienced mariners in the shape of the captain, Thomas Walker, aged 60, boatswain James Cumming, 52, and steward Charles Wilson, 55.

Yet, when they left their home city on that fateful summer voyage, it would be many months or years before they were given the opportunity to return to their roots.

Margie Mellis, whose great-grandfather, Mr Wilson, was among the unfortunate people who were caught up in the febrile climate at the beginning of the hostilities, has researched what happened to them in the book A Crew That Time Forgot: Rubislaw to Ruhleben, written with Doreen Black, who sadly died shortly after its publication.

The camp in which the crew – and more than 30 other Aberdonians – found themselves interred was part of a well-known racecourse frequented by Berlin’s pre-war elite.

But, after the conflict began, Ruhleben’s stables were cleared of horses to make space for the prisoners.

Little else was done to accommodate them as they took up residence within the horse boxes and hay lots and amid the smell of dung.

The Rubislaw, a steel-screw cargo steamer that was launched in 1904, was built by Hall, Russell & Co for the Granite City Steamship Company and, in addition to a large cargo-carrying capacity, the vessel had first-class passenger accommodation.

It was designed to boost the growing relationship between Aberdeen and Hamburg and the trade between the two cities had increased so much that, a decade later, the Rubislaw embarked on the round trip every 10 days.

The journey was uneventful and the crew arrived at their destination on August 2.

Even after the declaration of war, the Hamburg authorities informed Captain Walker that he would be allowed to depart and, by the time the vessel was ready to sail later that day, around 130 British citizens had crowded on board, anxious to leave Germany.

But all their hopes were dashed when German officials suddenly intervened and told the Rubislaw’s crew they would not be permitted to leave the port.

The book tells the story of the ship, the crew, and their families at home and describes how the different characters coped with their imprisonment.

It also highlights how they formed various groups and eventually transformed the barren landscape into flourishing gardens.

Some of the men were released early in December 1915, because of their age. These included Captain Walker, Mr Cumming and Mr Wilson, the latter of whom was married with five adult children and lived at 10 Summerfield Place in the city.

But others, such as engineer Robert Cameron, who was incarcerated in Barrack 11, Box 26 at Ruhleben, were forced to spend years in captivity away from their loved ones.

And there was an awful sting in the tail for Mr Cameron in particular.

Aberdeen cared about its captive crew

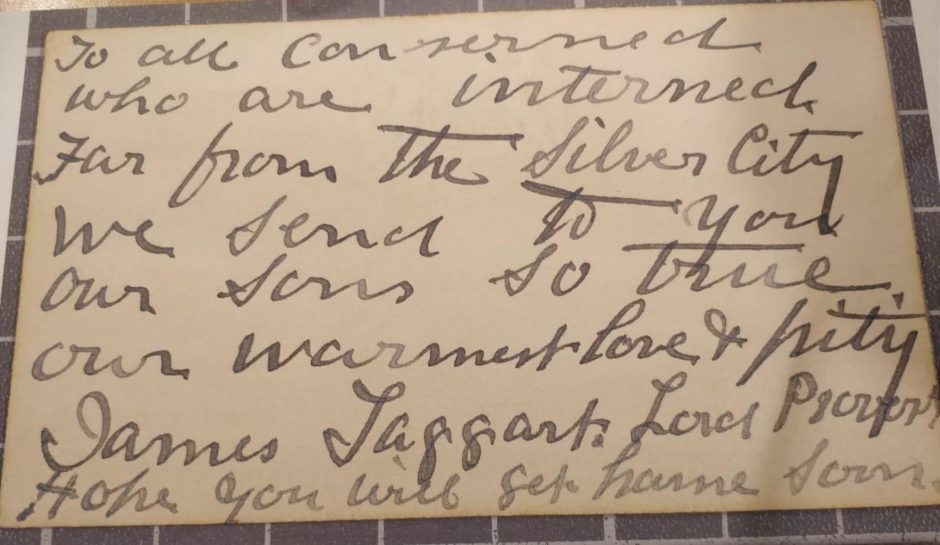

A Crew That Time Forgot provides plenty of evidence, both in words and pictures, of how the crew’s plight was felt by their fellow Aberdonians.

This was summed up in a reply sent by the then Lord Provost of Aberdeen, James Taggart, to a postcard despatched from the camp in 1914 in which the captives wished everyone in the city a happy and prosperous New Year.

Written in the Lord Provost’s own hand, the return message read:

To all concerned

Who are interned

Far from the Silver City

We send to you

Our sons so true

Our warmest love and pity

Mrs Mellis said: “My great-grandfather, Charles Wilson, was a ship’s steward and was only on the vessel because somebody else had either been dismissed or not turned up.

“It was pure chance – or bad luck – that he was among those who ended up in the camp. But we discovered so many of these things while we were working together.

“A query in the Aberdeen & North-East Scotland Family History Society Journal brought a helpful reply from a fellow member, who alerted me to the existence of the prisoner of war records in Aberdeen City archives.

“Articles which had appeared in the local press at the time furnished me with a wealth of contemporary information about the Rubislaw herself, and about the experiences of her crew and of some of her passengers.”

George Petrie’s wife was still holding his note in her hand when the port missionary and a representative of the company arrived to break the news.”

Margie Mellis

Mrs Black, whose grandfather, David Tulloch, was a prisoner, said in 2018: “When I helped my grandpa in his beautiful garden as a wee girl, I never imagined that his love and knowledge of gardening had been gained as a prisoner in the First World War.

“It has been fascinating to find out so much about the background.”

The conditions the prisoners endured were spartan and inhospitable. The nights were freezing cold, to the point where the inside walls and ceilings were frequently covered with ice and the men’s breath could be seen in the chill.

The food was almost inedible

The book relates: “Sanitary arrangements were completely inadequate. The men had to queue to wash in cold water which came from one tap and the latrines which had been dug for the prisoners were described later by the American ambassador as ‘a danger not only to the camp, but to Berlin’, such was the threat of infection.

“The months between November 1914 and February 1915 were very cold with bitter winds coming from Poland and Russia and the rain quickly turned the sandy soil of Ruhleben into a quagmire. Men found themselves ankle-deep in mud whenever they walked three times a day to queue for their food.

“This might have been more tolerable if the men had received adequate food. But it was in very short supply and, what little there was was almost inedible.”

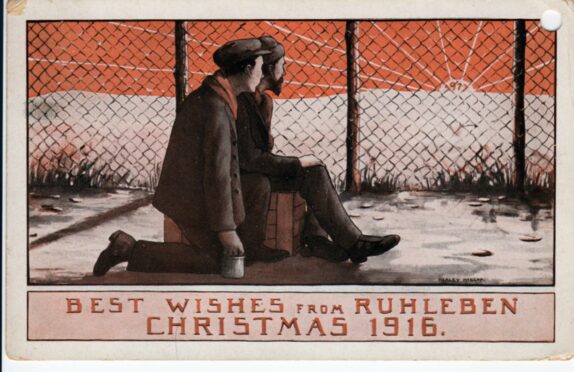

There was nothing to celebrate on that first Christmas in Ruhleben.

Thankfully, matters gradually got better for the north-east men. Given that Ruhleben was a civilian PoW camp, it was in the international spotlight and, at the outbreak of the war, the United States – which was a neutral country in 1914 – assumed responsibility for British interests in Germany.

The book reports: “Just a few months into 1915, the American ambassador, James W Gerard, visited Ruhleben for the first time and was appalled at the poor sanitation and the overcrowded conditions in the camp.

“As a result of his complaints, improvements were implemented and some men were released, but only those who were unfit for military service.

“In December 1915, after 17 months of captivity, Charles Wilson was released from Ruhleben, but after his return to Aberdeen, never spoke about his time as a PoW.

“He had experienced the worst of Ruhleben, the appalling conditions, the sometimes brutal treatment by some of the guards, the inadequate food, the lack of purposeful activity, the boredom.” And it was a closed chapter in his life.

Others remained in confinement until the end of the war in 1918. By that point, they benefited from a food parcels service and were spared the horrific carnage which had engulfed large parts of Europe and led to millions of deaths in the trenches.

But even after they had returned home, they were haunted by war. And although the Rubislaw resumed operations with Hamburg, it proved an ill-fated vessel.

On November 28 1939, just a few months into the Second World War, the Rubislaw struck a mine off the south-east coast of England and sank within two minutes.

Most of the crew went down with the vessel and only four sailors survived, after they were rescued by a passing mine-sweeper.

Some of these sailors were the same people who had been on the ship before the conflict and had spent the war years as prisoners in Ruhleben.

Trade between the two cities continued up until the summer of 1939, just before the outbreak of the Second World War, when the Rubislaw was taken off the Hamburg route and switched to coastal duties.

It was while carrying a cargo of cement from London to Aberdeen that she struck the mine.

The tragedy was reported in detail in the Press and Journal, which revealed the heartache and hardships of the families left at home.

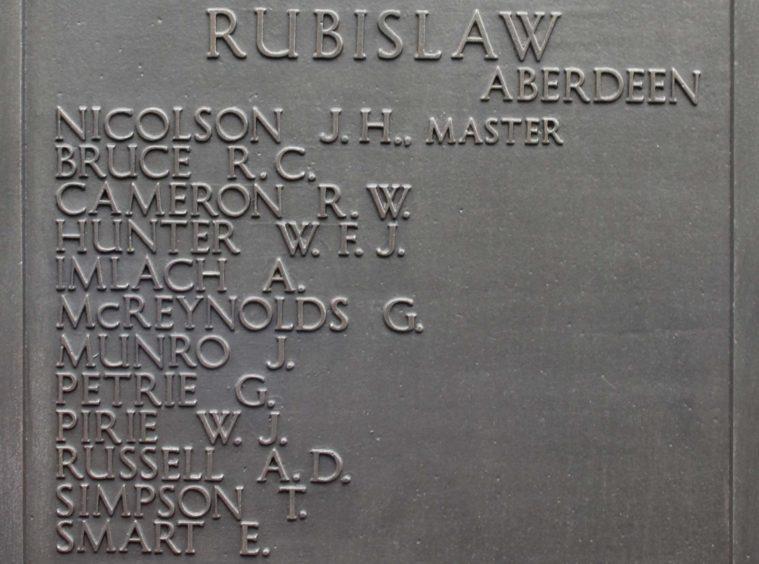

The captain, James Nicolson, had been on the Rubislaw for 14 years, first as mate, then master. He and chief officer Alexander Imlach were on the bridge as the ship sank.

And Robert Cameron, who spent four years in captivity at Ruhleben, but had advanced to the role of chief engineer, was another of the victims of the disaster.

Alexander Dyce Russell had been with the Rubislaw for four years. His grandson, William Stevenson, spoke about the impact it had on his whole family.

He said: When my grandfather was lost with the ship, he left a widow and seven children, two girls and five boys.

“His youngest daughter, Stella, his last surviving child, mourned her father until her death in 2014.

“He was among the first of many thousands of men who gave their lives and my family were some of the hundreds of thousands who subsequently bore the lifetime loss of those nearest and dearest to them.”

Margie Mellis said: “The sinking of the Rubislaw was a tragic case, but it made me think about all the other merchant seamen and fishermen from the north-east who lost their lives in both world wars, and of their families at home.”

“Wives, mothers and children were expecting the men back by the weekend, and many had received messages from the men to that effect.

“George Petrie’s wife was still holding his note in her hand when the port missionary and a representative of the company arrived to break the news.”

The names of those who died are commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial in London, which was created by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to remember Merchant Navy seamen and fishermen who have no grave.

Or, at least, no grave but the sea.

- A Crew That Time Forgot is published by the Leopard Press.