The current headlines about panic at the petrol pumps and supermarkets running out of supplies have sparked a wave of woe-is-me responses.

One might imagine Britain was lurching through an unprecedented crisis with the army being called in to help deal with everything from driving ambulances to HGV lorries.

Yet for those of who grew up in the 1970s, living with power cuts, wildcat strikes, three-day weeks, endless political machinations and elections, rows between management and trade unions and empty shelves were a familiar part of our existence.

As a teenager in 1974 – a year of two general elections and apparently endless arguments between Ted Heath and Harold Wilson – we were used to being told to expect nights of darkness and advised to stock up on candles and firewood.

Living in a mining town in West Lothian, at a time long before the creation of the digital appliances and mobile devices we now take for granted, a lack of fuel shouldn’t have been an issue.

But it was and this was in the days when almost everybody had a coal fire in their (rented) properties.

When the miners went on strike – and most of us instinctively sympathised with them in the 1970s – it caused genuine problems for the public, especially the elderly who were reliant on keeping their homes heated.

Yet there are many major differences between the present situation and what happened nearly 50 years ago.

For starters, even in the midst of strikes and with rubbish building up on the streets, communities still pulled together.

There was none of the hostility which pervades social media, none of the wall-to-wall TV coverage of petrol stations and shopping malls which now dominates the airwaves.

I have never forgotten some of the miners, who were taking industrial action, making sure they gave coal to their more vulnerable neighbours and ensuring they remained warm in winter’s grip.

As Davie Bryce, a union official in West Lothian, said: “Our argument is with the National Coal Board, not the people.”

It was the same when basic foods such as bread, meat, fish and milk were in short supply.

For the most part, you bought what you needed or could afford and didn’t leave others with nothing. And besides, precious few of us owned fridges or freezers.

Not everybody stuck to the rules

It would be simplistic to pretend there wasn’t occasional frustration at the sight of a railway station being closed, with commuters left to wait for hours.

Dundee author and journalist James Cameron was among those who grimaced at the impact of the “Winter of Discontent” in 1978 and 1979, which eventually led to Margaret Thatcher’s overwhelming election success in May.

As he wrote: “When I went into my modest (railway) station a couple of days ago, I though momentarily that I was in a graphics exhibition.

“One chalked sign said: ‘No phones working’. Another said: ‘Lift out of order’. Yet another read: ‘Ticket machine not in service’. Finally, another said: ‘No lavatories’.

There must have been lots of older folk for whom things were a whole lot tougher.”

Jim Hunter

“At that point, they must have run out of chalk, because it was left to the out-of-service lift man to tell the customers that, in any case, there were no trains running because of some unspecified defect on the line.

“He told me: ‘Make your way to another station, they might just be okay there’.

“But, since a station which has no lifts, no tickets, no phones, no lavatories and, in particular, no trains does not quite fulfil my exacting standards, I went home.”

He wasn’t alone on the road to nowhere during these fraught months.

It was a big adventure for many youngsters

However, it would be stupid to argue that we were a depressed, dispirited bunch, left traumatised by the disruption, in the 1970s.

Those of us who were young had no experience of anything else. If anything, it was exciting to have a torch, a book or magazine and portable radio (and plenty of batteries) in the middle of a power cut.

The darkness didn’t present a problem and even the cold could be tackled with jumpers and cardigans and enough warm covers.

If there was little on the shelves, once again it hardly mattered. I still recall my mother being left speechless when one of her church choir friends told her: “I don’t know why there’s any problem with panic buying – I have 20 loaves in the pantry at home”.

But she was in a minority. She was one of the few Conservative supporters in a town that would have voted for a scarecrow in a field if it sported a Labour rosette.

Dark nights didn’t mean dark moods

Jim Hunter, who is now an emeritus professor at the UHI, was among those who dealt stoically with the blackouts and recalls his generation rising to the challenge.

This, let’s remember, was happening less than 30 years after the end of the Second World War, where people endured far worse than occasional strikes and shortages.

As he said: “The rolling power cuts of the early months of 1974 found us in Edinburgh where I was completing my PhD thesis and where (his wife) Evelyn was teaching.

“We were living in a rented flat and one of our lingering memories concerns the complexities of having three or four friends round for a meal.

“We would study the power cut schedule which was published daily in the Evening News and work out who among us would be best placed to do the cooking by virtue of having early-evening power.

The whole thing was more fun than horror for us then.”

Jim Hunter

“We recall getting a casserole cooked and then, when the lights were about to go out, loading it into a carrier bag and heading off to one of our friends’ places where the lights were about to come on, have our meal and head home to find our own lights about to come on again. And all this by bus.

“The whole thing was more fun than horror for us then. And, of course, we were all on the side of the miners and very much hoping that the eventual outcome would be, as it was in the event, the downfall of Ted Heath (and his government).”

It was another time, another world.

The ’70s was a decade of political ferment and rapid change. In the circumstances, it was hardly surprising it often felt the lights might go out at any moment.

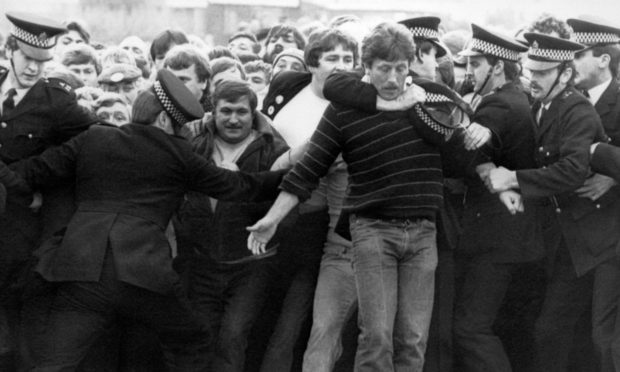

There were even plans, discussed but not carried out, of a military takeover of the country, and Thatcher eventually prevailed in defeating what she called “the enemy within” at the height of her domination in the 1980s.

But those of us in our teens were oblivious to all that. If there was nothing on TV – and there were only three channels – we went out and kicked a football, swung a golf club or joined the community centre or local boxing/cricket/athletics/amateur dramatic society.

And besides, we had the emergence of David Bowie, Marc Bolan, Queen, Led Zeppelin, Abba, The Who and the Bay City Rollers to suit all our different musical tastes.

So we just got on with it. There was no alternative, as a certain Iron Lady later declared.

Was it a tougher generation?

Jim Hunter is among those who can’t quite believe the Cassandra-style headlines in the current media, let alone people beating each other up on garage forecourts.

He said: “The only real lesson to be drawn from my reminiscences is that, when you are young, you take all sorts of difficulties in your stride.

“There must have been lots of older folk for whom things were a whole lot tougher. But then, they had been through the war, they had seen its horrors at first hand and had lived for many years with rationing.

“Power cuts must have looked pretty piddling in that context. And, as for the weeping and wailing which we now witness when supermarkets run short of toilet rolls, it would strike them, I reckon, as pathetic.”