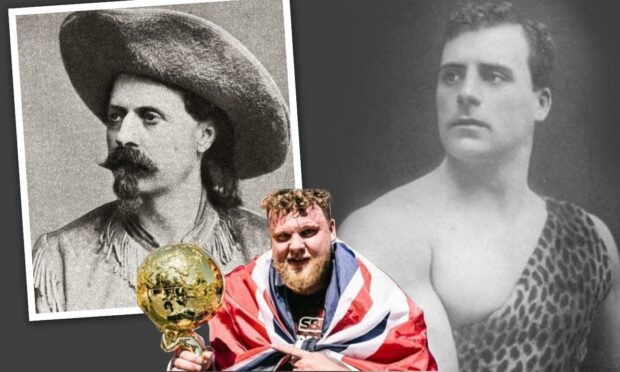

He was the north-east circus performer who earned fame throughout the world as the Scottish Hercules.

And such was the grisly power and athletic prowess of Banff-born William Bankier that he elicited gasps of astonishment from none other than Buffalo Bill, who described the Scot as one of the strongest men in the world during the Victorian era.

However, this fellow wasn’t simply renowned for his ability to make audiences gasp.

He was also a sharp-witted entrepreneur with a passion for wrestling and martial arts who found himself embroiled in various spats and court cases with rival promoters which made headlines and heightened his reputation as the Don King of his generation.

Not bad for a youngster who ran away to sea and was shipwrecked off Montreal: an incident that gained him admission to a thrilling world of performing with many of the globe’s most famous circus acts, thousands of miles from his birthplace.

And that was years before he met the distinguished artist John Everett Millais, who persuaded him to change his name to Apollo.

From Banff to Montreal in risky waters

As the eldest of four sons of William Bankier, a hand loom weaver, and his wife Mary Ann, nee Clark, the youngster, born in 1870, was fascinated by acrobats and clowns, and magnificent men and women on the flying trapeze and rapidly reached the conclusion that staying in a backwater coastal area would stifle his dreams.

So he did what any aspiring star would have done and ran away from home at the age of 12 and joined a travelling circus as a labourer.

His father soon discovered his whereabouts and brought him home, but his son was not to be thwarted and, just a few months later, Bankier ran away to sea, joining a ship’s crew and pretending to be older than he was, which wasn’t difficult since he was already turning into something approaching a man-mountain.

Even being shipwrecked in turbulent Atlantic waters didn’t dent his swagger, nor pour cold water on his grand plan after he found himself in Canada and worked as a farm labourer, acquiring the knack of lifting more and heavier bales.

The crowd, understandably, was rich in its appreciation.”

Review of Bankier’s performance in 1893

Aged only 14, this incredible hulk joined Porgie O’Brien’s Road Show where one of the acts was a strongman; and while the latter quaffed as many pints as he pumped iron and started missing shows with hangovers, his apprentice studied his act, learned his routine and was ready to step into his shoes when the opportunity presented itself.

Within a year, Bankier was recruited for another performing show by Greco-Roman wrestling champion William Muldoon, a rugged entrepreneurial spirit who ignored his new signing’s Caledonian roots and billed him as “Carl Clyndon, the Canadian Strong Boy” and the public quickly flocked to marvel at his antics.

Muldoon’s show – a variation of the Highland Games staged every year across Scotland – featured a series of athletics and sporting events and Bankier gradually developed wrestling skills in addition to linking up with Jack Kilrain, a former heavyweight boxing champion, who helped him in the fistic arts.

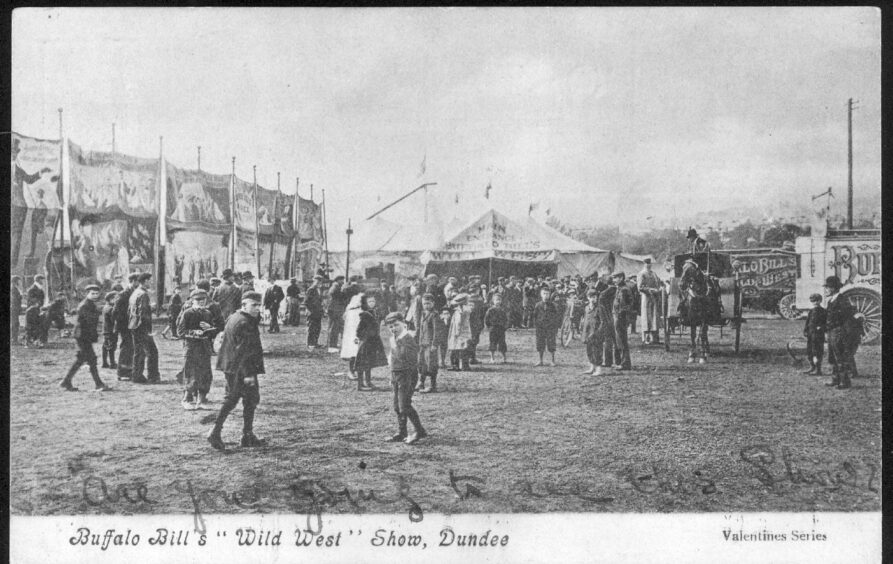

But the lure of the circus was still overwhelming and Bankier joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, one of the globe’s biggest touring companies.

By this point, he had gained a reputation for heavy lifting of the variety that normally required a crane.

Indeed, fuelled by a Bunteresque appetite and a gruelling fitness regime, he was like Popeye after an overdose of spinach.

Buffalo Bill wanted to retain his services but others were challenging his domination and Bankier rapidly became a member of the expanding Ginnett Circus.

He was continuing to use the name Carl Clyndon – it meant that nobody could track him down, least of all his parents, who must have been worried sick – and, after turning 20, the 1890s were his prime years of carrying out almost miraculous exploits.

Once he joined the acclaimed Bostock Circus, Bankier started mastering his repertoire of Herculean labours, which included such things as wearing a harness and lifting an elephant weighing about 3,200 pounds.

It may sound ridiculous, but he was able to balance on the backs of chairs while holding a man overhead with one hand and juggling with the other; tricks or pieces of improvisation he had refined and fine-tuned in the previous decade.

One review in 1893 said: “We would not have believed that any human being could undertake these exertions without serious injury, but this fellow makes them seem a natural part of his routine.

“The crowd, understandably, was rich in its appreciation.”

The birth of the Apollo mission

There was nothing conventional about this redoubtable individual’s life.

Even when he decided to travel back to Britain, he was involved in writing a book about physical culture and how he had transformed himself into a tower of strength.

But he didn’t hang around with other sporting competitors or indulge in games for their own sake.

On the contrary, he became friends with the painter and illustrator Sir John Everett Millais, who encouraged him to be billed as “Apollo, the Scottish Hercules”.

Bankier was impressed with the suggestion and it was under this name that he toured the world performing for large audiences and receiving glowing accolades.

An early rivalry set the tone

In 1900, he published his work, Ideal Physical Culture, but was soon involved in the first of many wars of words with somebody he perceived as a rival.

Eugen Sandow had achieved fame and recognition in both Europe and the United States and was the darling of the Stateside press when Florenz Ziegfeld – of Ziegfeld Follies fame – included him in a display at the World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893.

As one report stated: Sandow performed a number of strong man feats, but the audience seemed more interested in his muscles than the amount of weight he lifted, so Ziegfeld developed a kind of ‘posing routine’.

“These were called muscle display performances and he performed these at many different exhibitions and was filmed by Thomas Edison doing his routine.”

Bankier, who had heard all about this arriviste, was distinctly brassed off.

The Scot denounced the ‘charlatan’

Therefore, wasting no time to turn a kerfuffle into a full-scale row, he challenged Sandow to appear in a contest of weightlifting, wrestling, running and jumping.

Then, when the offer was snubbed, Bankier called him ”a coward, a charlatan and a liar”.

Strong stuff, but he went even further in 1904. “Picture a man tripping on the stage with the short pitter-patter of a fussy little woman with sore feet trying to avoid treading on a companion’s dress, and forcing herself to look amiable.

“That is exactly how Sandow walks upon the stage.”

As you might expect, there was no love lost between these characters. But that summed up Bankier.

He had learned from Buffalo Bill that old-fashioned “row stories” are the stuff of dreams to the media. And it was a trait he maintained for the rest of his days.

Ascending into a different world

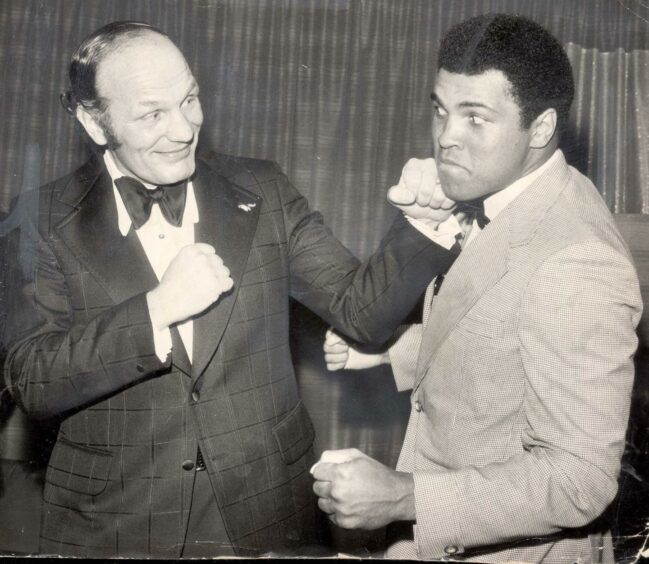

After retiring from the stage, Bankier joined forces with with Monte Saldo, formerly of strongman act The Montague Brothers, and they opened the Apollo-Saldo Academy in London, which was a haven to many of the most famous lifters and wrestlers of the day.

These included such luminaries as now-long-forgotten figures George Hackenschmidt, Ferdy Gruhen, Maurice Deriaz, Zbysco, and the winner of more than 1,000 contests, the lightweight wrestling world champion and a gold and silver medallist at the 1908 Olympics in London, George de Relwyskow, who was a behemoth in his own right.

He also moved into wrestling promotion, and among his clients was Yukio Tani, a Japanese jujutsu instructor and professional challenge wrestler.

In partnership with Tani, he founded the British Society of Jujutsu, then, in 1915 and 1919, he was ‘King Rat’ of the British showbusiness charity the Grand Order of Water Rats.

This organisation later featured such stars of sport and TV as Henry Cooper, Les Dawson, Roy Hudd, Paul Daniels, Frankie Vaughan, Joe Pasquale and Rick Wakeman.

Bankier was in his element, as always, when there was a spotlight shining on him.

Wrestling with the public and the courts

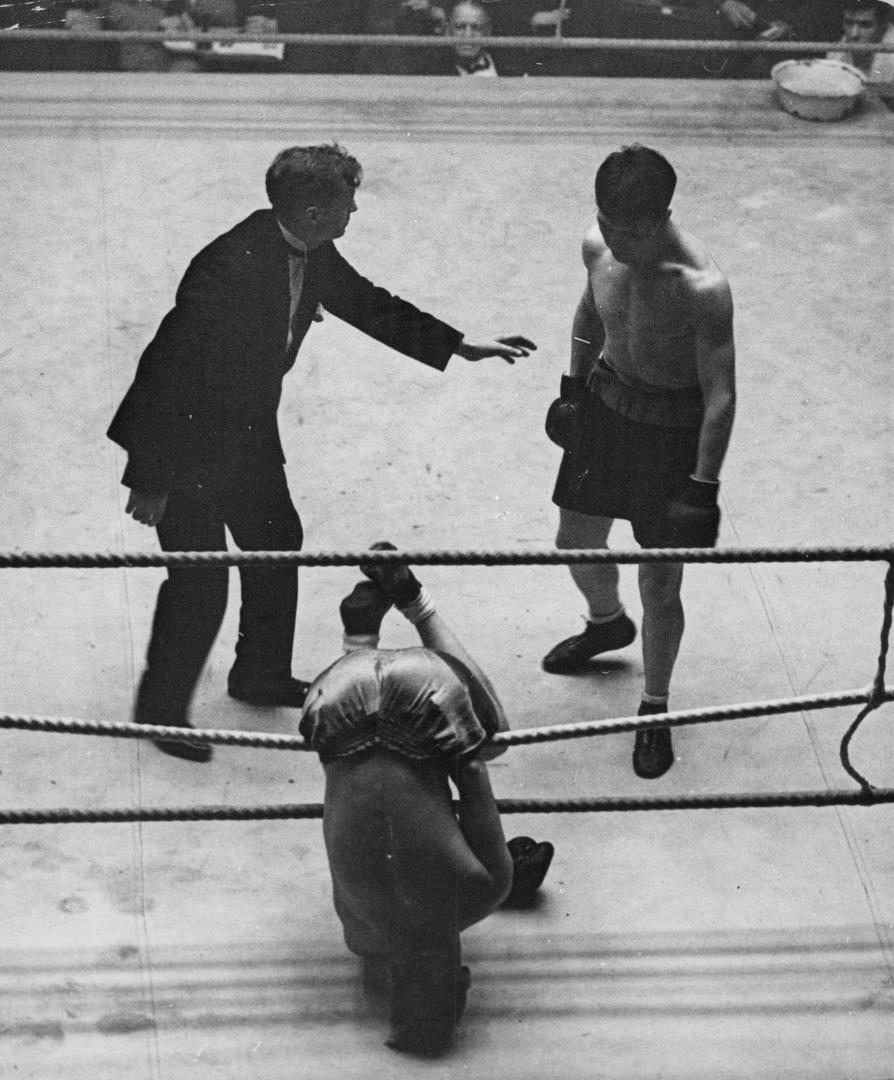

In 1933 the Nelson Leader reported on a “joyous evening” of wrestling presented by Bankier at the Imperial Ballroom in the Lancashire town.

It said: “This man marvel Apollo is to be congratulated, not only on the show he staged, but his chatty remarks and the calibre of the wrestlers he introduced.

“One of the old-timers was Mr Walter Place, better known a generation ago as ‘Big Walter’, who, so stated Mr Bankier, was one of the best wrestlers in the country.

“Another old sportsman to be presented was Peter Bannon of Burnley, who, according to Mr Bankier, was one of the greatest wrestlers of all time.”

And so it continued. One suspects the report might have been penned by Mr Bankier!

Stormier waters lay in store

In the years ahead, Bankier was in court almost as regularly as Andy Murray, claiming breach of contract against boxing promoter John Mortimer; and being sued by professional wrestler Leo Lightbody for breach of contract and damages.

Then, in an expensive case, a jury awarded £800 damages to Ivan Serie and £300 to William Garnon, known respectively as Jack Sherry and Bulldog, following defamatory comments made by Bankier in the programme for a series of bouts in Liverpool in 1936.

It wasn’t just in and around a boxing/wrestling ring that he garnered headlines. There was another incident highlighted in the Press & Journal the following year.

Another ring was involved in a drama

It read: “Bob Gregory, the all-in wrestler, and Miss Valerie Brooke, daughter of the Rajah of Sarawak, made an unsuccessful bid to be married in Liverpool on Saturday.

“Gregory met Miss Brooke after he had wrestled at Lane’s Club, London, on Friday night and they dashed by taxi to Euston to board the north-bound night express.

“Arriving in Liverpool early on Saturday morning, they got Mr William Bankier, wrestling promoter, out of bed and began a chase around the city, for a special (marriage) licence, which they were unable to obtain.

“The young couple then stayed with Mr Bankier and, later, he took them by plane to Belfast, where Gregory had agreed to wrestle on Saturday night.

“We only formulated this plan at the last moment,” said Gregory. “It failed and now we have made up our minds not to get married until nearer Christmas.”

A life packed with incident

Bankier was rarely out of the media gaze during his life, but there was no sign of obituaries in the mainstream Scottish press when he died, aged 79, in 1949.

By that stage, he had been living and working in England for so long that precious few people were aware of his Scottish roots.

But, however posthumously it might be, this mercurial man deserves a good send-off.