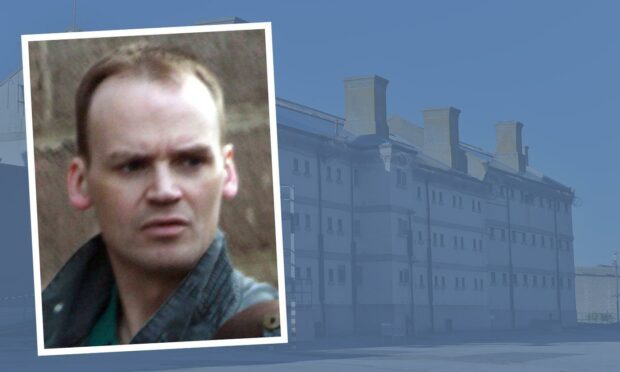

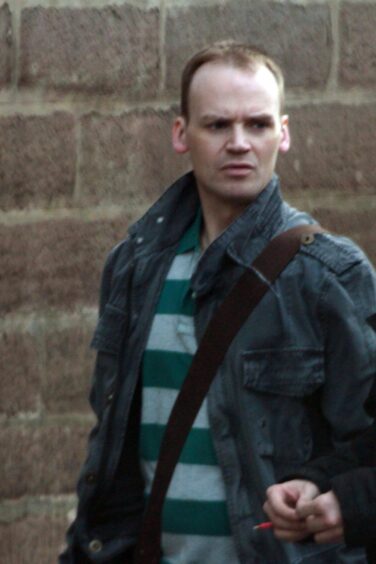

The Press & Journal’s front-page headline on October 4 1996 could hardly have been any more graphic: “Terror grips town after murderer flees”.

But there was nothing low-key about the response of the police and council authorities to the news that convicted killer, Thomas Gordon, had escaped from his guards while being escorted to hospital and was on the loose in the Blue Toon.

It was another reminder of how dangerous some of the prisoners incarcerated at the institution, dubbed the “Hate Factory”, were regarded by the authorities.

The police brought in a helicopter and tracker dogs to hunt down the Dundee man, who had been sentenced to life imprisonment at the High Court in Glasgow in 1989 after stabbing to death a teenage inmate in the cell of a young offenders’ institution.

But they would have no joy in their quest during the next 10 days of frenzied activity.

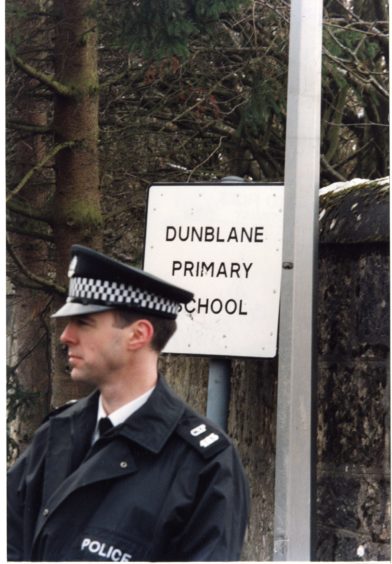

Fears surfaced of another Dunblane

Within hours of his escape, the P&J had produced hundreds of Wanted posters on behalf of Grampian Police, and these were distributed to shops and businesses in and around Peterhead as news spread throughout the north-east community.

And the gravity of the situation was soon obvious when schools in the town were hurriedly closed and children whisked home by worried parents amid fears – this happened just a few months after the Dunblane Massacre – that Gordon might target teachers or pupils and try to use them as potential hostages.

This was no idle threat, considering he had previously been involved in a hostage-taking incident at Perth Prison and the revelation he was one of six prisoners held in a 10-man unit at Peterhead Prison for those who “did not fit into the normal prison regime”.

How did he escape?

It emerged that Gordon had been handcuffed while he was entering the hospital, but the restraints were removed during his physiotherapy treatment.

And, sensing his opportunity, he gave officers the slip by running into the garden of a house in Cairntrodlie and scaling a wall.

An 18-year-old passer-by, Jamie Urquhart, spotted him sprinting across the grass shortly afterwards at 11am and told the P&J: “I saw this man in grey running straight towards me with a prison warder chasing in pursuit.

“He ran into one of the gardens here, still followed by the officer, but then I heard the officer shouting: ‘I have lost my prisoner.”

Staff described confusion and commotion

Staff at the hospital subsequently spoke of how Gordon had capitalised on the situation with one saying: “We were giving a team briefing when, suddenly, we heard a noise.

“Then, his [Gordon’s] physiotherapist ran in and said he had escaped. I think she was more taken aback than scared because none of us knew he was in prison for murder.

“We heard the vans screeching after him, and a couple of officers raced outside, but they could not reach him before he was gone.”

A tight police cordon was immediately thrown around the town and road blocks were mounted on strategic routes leading from the town and in Aberdeen.

Then it was time to think about the schools in the area.

Within the next two hours, word spread like wildfire about what had happened and Aberdeenshire Council implemented the closure of local schools.

A spokeswoman for the authority said they feared that “the man might try to take children or teachers hostage”, given the prisoner’s history and with the ghastly memory of the Dunblane Massacre still fresh in people’s minds.

But, even though there was no official confirmation of Gordon’s movements as the afternoon advanced, mothers in Peterhead spoke about their anxieties.

Residents were scared and ‘petrified’

Police raided a property in the town’s Kirk Street about 5.15pm, following a call from a female resident who thought she spotted a man in her back garden, with her gate open.

Eight officers, including plainclothes detectives, searched the house and garden with two sniffer dogs, but found nobody inside, although the woman spoke about how she and her two children had been frightened by the day’s events.

She said: “I called the police straight away because I was too scared to go inside and check. It was absolutely terrifying. I picked up my kids from school and heard that this man was still on the loose.”

Another resident, Carole Strachan, who lived in nearby West Road, said she was petrified and dashed to the school as soon as she could to collect her two children.

She added: “I had been at a computer course and, when I returned, my friends told me that this man had escaped.

“We’ve all had to act as quickly as we could.”

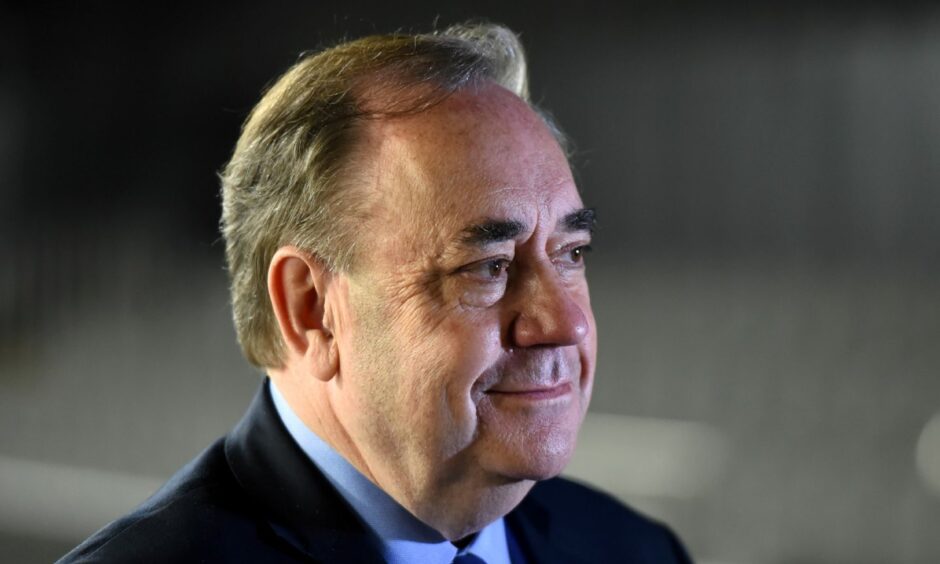

Alex Salmond was on the warpath

Even in the midst of the manhunt, the future First Minister Alex Salmond, who was at that stage the MP for Banff and Buchan, demanded answers as to how Gordon had eluded the guards without anybody laying a finger on him.

He called for an inquiry, stating: “The local community deserves to know how on earth a dangerous prisoner could be allowed to escape so easily.

“The community also needs to be reassured that appropriate security measures are in place whenever prisoners are escorted on journeys outwith the prison gates.”

There was no shortage of developments while the search continued for Gordon.

But as days passed, the police still had no firm idea where he was, even though they discovered he had made a phone call just minutes after his break-out at a property in Peterhead.

Superintendent Keith Wilkins, who was leading the manhunt across the north-east, confirmed that Gordon had called at a property in the town and asked the female occupant if he could use her telephone.

He said: “She allowed him to do so and he left the house shortly thereafter. Throughout his short time at the house, Gordon behaved calmly and made no threat of any kind towards the woman.”

The trail had gone cold

There were reports that he might have tried to return to his old patch in Dundee, and even sightings as far afield as Perth and Greenock, but several leads came to nothing.

In the meantime, four men appeared at Peterhead Sheriff Court in connection with the case, were charged with attempting to defeat the ends of justice, and remanded in custody.

Officers continued to appeal for help from the public, but admitted that he might be receiving help and shelter locally in Peterhead.

A spokesman said rather forlornly: “He could be heading for Dundee, but really, nobody knows where he is off to. I wish we did.”

And so did the public.

However, more than a week after his escape, he was still at large and the focus switched away from the Blue Toon, with a terse report in The Courier on October 14.

Police were increasingly baffled

This read: “The hunt for Thomas Gordon continued in Dundee at the weekend. On Friday [October 11], there had been a possible sighting at Kirkton.

“There had also been a reported sighting of Gordon a mile away at the Edzell Court multi in the afternoon.

“It is now 10 days since he went on the run having escaped from guards while being treated in hospital for a stab wound.

“Police have urged anybody with information to come forward.”

Yet the frustration was becomingly increasingly evident. All their efforts had led to the arrests of people who had helped Gordon – and accidentally snared a drink-driver – but there was a definite sense of “What do we do next?” in some of these despatches.

The final breakthrough came in London

Thankfully, though, the Press & Journal had positive news on Tuesday October 16 when it carried the headline: “Escaped killer recaptured after tip-off”.

The accompanying story offered relief to those who had been waiting for the news, but there was also some embarrassment for officials in the lack of clear communication between different police forces across Britain.

It said: “Escaped Peterhead prisoner Thomas Gordon was recaptured yesterday after a tip-off from a member of the public. The killer was arrested by British Transport Police at Victoria Station at lunchtime.

“But it is believed Grampian officers continued carrying out inquiries to discover Gordon’s whereabouts for several hours after his capture – seemingly unaware that the wanted man was at London’s Belgravia police station.”

The report detailed how a “bemused” Gordon had been caught while he was in possession of a pair of sharpened scissors, but surrendered peacefully.

He had previously been reported to New Scotland Yard around noon by an anonymous source, but the BTP’s Inspector Andy Ball dismissed speculation this had come from an “eagle-eyed Peterhead woman who was on holiday in London”.

He said: “As far as we are aware, no female was involved at all. My understanding is that there was an anonymous phone tip-off from a man saying that the prisoner was coming down to London. All we had to do was position officers at the mainline stations and it was quite easy to pick him up.”

After a night in custody, Gordon was taken back to Scotland the following day, even as Grampian Police said a report would be sent to the procurator fiscal.

It was a happy ending which still left several unanswered questions and concerns.

The Government ruled out an inquiry

Despite concerns raised by SNP and Labour MPS, the Government ruled out a top-level inquiry into three escapes from custody, including Thomas Gordon, in the space of three days at the start of October.

Speaking during a visit to Aberdeen Prison, Scottish Office minister Lord James Douglas-Hamilton said a ministerial investigation was “not necessary”.

Eventually, a Peterhead prison officer was sacked following Gordon’s escape, although he later went to an industrial tribunal claiming unfair dismissal.

Mark Callaghan was in charge of Gordon, with a more junior officer – who was fined £1,000 and had his probationary period extended – when the prisoner made his successful break for freedom. Their punishments sparked “outrage” among the Scottish Prison Officers’ Association, who revealed in the P&J that “morale was at rock bottom”.

Mercifully, the incident did not have more serious consequences.

Gordon was sentenced to another two years for his actions and was transferred away from Peterhead.