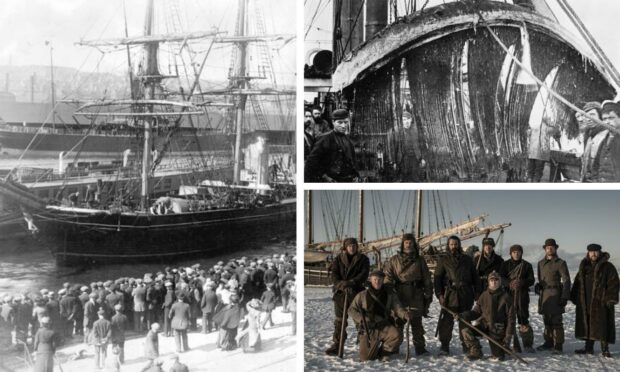

North and north-east whalers risked their lives to pursue the ‘great bounty’ for longer than any other city or nation.

Ships stalked the waves until the outbreak of World War One to kill whales using open boats and a harpoon attached to a heavy rope.

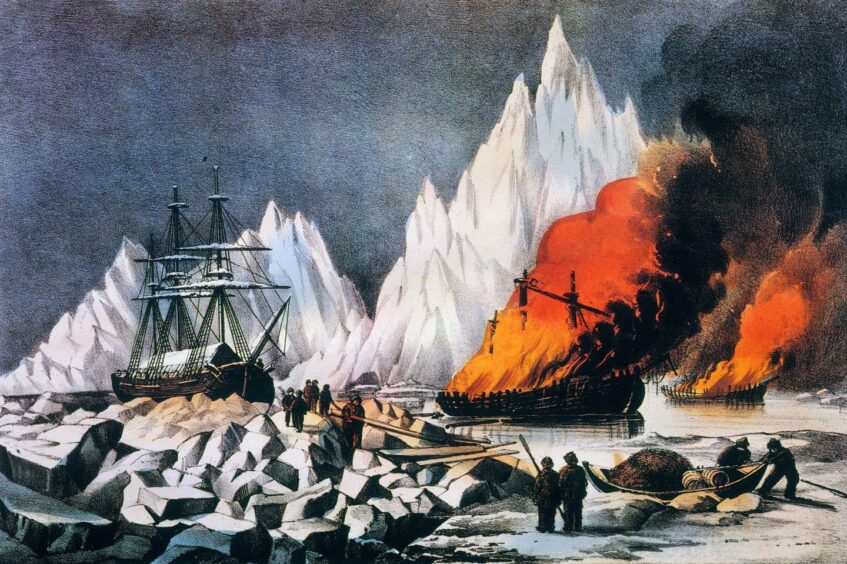

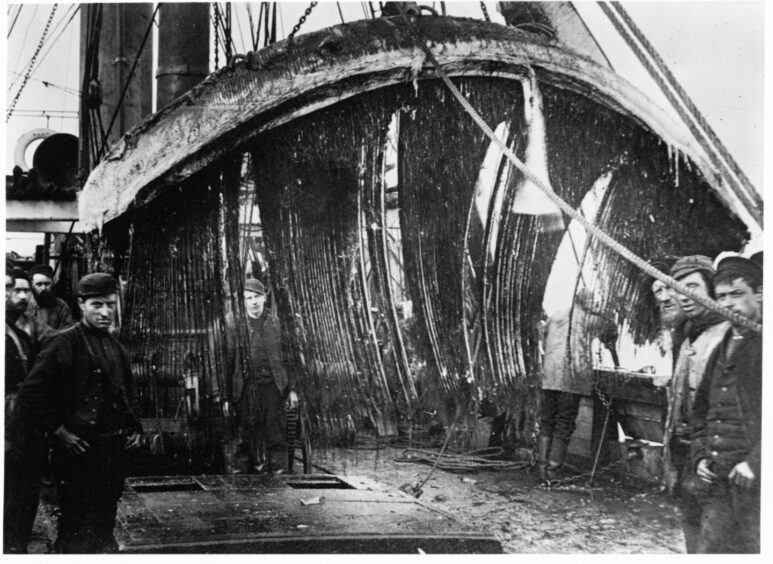

Whaling was more mortal combat than straightforward hunt and required some of the most dangerous, difficult and disgusting labour of any industry of the time.

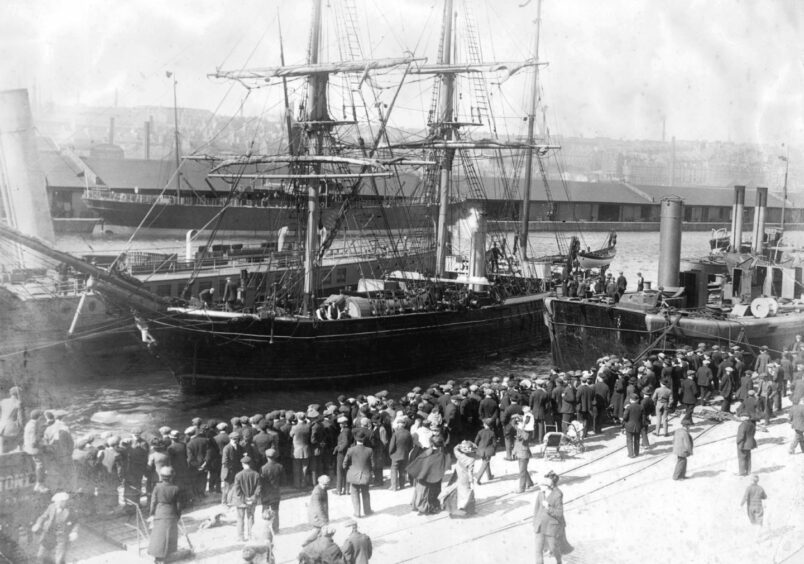

The trade was vital to Dundee, for jobs and industry, with oil used first primarily for lighting and then as a vital component in one of the city’s other major trades, jute.

Men drawn mostly from Scotland’s east coast and more latterly the Shetland and Orkney islands made at least 160,000 man-trips, crewing more than 3,400 vessel voyages.

Doomed voyage

This was a gory business which inspired the book behind BBC series The North Water which tells the story of a doomed voyage to the Arctic by a ship from Hull.

Viewers have lavished praise on the star-studded new series which well captures many of the hard-to-believe realities of the whale-hunting industry in the 19th century.

Professor Chesley W. Sanger has researched the 3,641 whaling voyages which cleared variously from 16 Scottish ports between 1750 to World War One.

He said: “While the series is based on ‘extensive research’ it tends to emphasise ‘English’ participation to the detriment of the Scottish component, which is not surprisingly perhaps, given the targeted audience, and general lack of understanding of the changing composition of British whaling over time.

“It is, of course, only ‘historical fiction’, but the loss of Newcastle’s last whaler, the Volunteer, determines the 1859 setting, for example.

“It appears to be the sole reason that year was chosen as the temporal setting.

“Yet, the Volunteer and six whalers from Hull represents the total English effort that year, while five Scottish ports fitted out 48 vessels which brought back 125 whales.

“Within a decade Hull also withdrew.

“Scotland, on the other hand, controlled eastern Arctic oil and bone markets until World War One brought the industry to a close.”

Professor Sanger grew up in Newfoundland in Canada before spending a sabbatical in Dundee in 1977 to conduct research on Scotland’s role in Arctic whaling.

The hand-written statistics he collected from various sources and old newspapers in Dundee, Aberdeen and Peterhead were digitised with the assistance of the New Bedford Whaling Museum in 2020 to make the data more accessible and to preserve it for generations to come.

Professor Sanger said the Arctic industry contributed mightily to the growth of Scotland’s whaling core and significantly influenced the history of the country.

“Throughout its lengthy history commercial whaling has been characterised by recurring cycles, with each distinctive phase following a pattern of discovery, exploitation, overexpansion, fierce competition, rapid stock depletion and, in time, diminishing profits, exhaustion and decay,” he said.

“Scottish Arctic bowhead whaling followed this sequence in all important details.

“My research shows that Scots participated periodically in Arctic whaling as early as 1625.

“Continuous involvement, however, dates from parliament’s decision in 1749 to raise the supporting bounty to forty shillings per ton.

“By 1757 Scotland’s Arctic fleet had increased to 15 clearing from Firth of Forth harbours including Edinburgh, Dundee, Aberdeen and Anstruther.

“The ‘Great Bounty’, then, acted as a trigger mechanism enabling Scots to pursue a realistic response to initial whaling opportunities, followed by perseverance in the face of wartime adversities, that enabled them to establish a small, but firm, foothold in Arctic whaling, with the industry, over time, being centred in east coast ports which had experienced fishermen, cheap labour, and proximity to the northern whaling grounds.

“The trade quickly became a major contributor to the economies of centres such as Anstruther, Aberdeen, Bo’ness, Dunbar, Dundee, Kirkcaldy, Montrose, Peterhead and Kirkwall.

“Vessels required annual overhaul and frequent repair.

“Properties were purchased and sizable structures constructed for processing and storage.

“The crewing of ships and the operation of rendering yards also provided new sources of employment and income directly.

“Indirectly, the seasonal preparation and provisioning of whalers brought benefits to virtually every merchant and tradesmen in the sponsoring towns, and to many famers in the rural hinterland.”

Growth and decline

There were five clearly defined phases of growth and decline between 1750 and 1801 which was the result of a complex set of often contravening forces.

Scotland’s industry entered a stage of maturity and consolidation which permitted further expansion after the French Revolution.

Professor Sanger said Scottish whalers had finally served their apprenticeship and were “poised and ready to outstrip their English rivals”.

He said: “The northern industry had become firmly established as an important tradition and the stage was set for the beginning of the ‘golden age’ of Scottish Arctic whaling.

“Scottish masters, Muirhead (Leith) and Valentine (Aberdeen), initiated the revival by showing the drive and enterprise that had characterised their fellow countrymen’s involvement throughout the entire history of the trade.

“They sailed north along the west coast of Greenland and across Melville Bay in 1817 and 1818 after what normally would have been the close of the season at Davis Strait.

“Their initiative led to the opening of the Baffin Bay whaling stations, thus significantly expanding the catching window.

“In so doing, however, it also hastened the pace at which the western North Atlantic stock would be depleted.

“Not recognising, or more likely, simply ignoring the lessons of overfishing that should have been learned on the older Greenland Sea and southernmost Davis Strait hunting grounds, owners embarked upon yet another period of rapid growth.”

Scottish participation peaked at 60 whalers in 1821 and two years later when the bounty was finally eliminated, they replaced the English as the most important suppliers of Arctic oil and bone.

That success, not surprisingly, was short-lived.

With the last refuge of the North Atlantic bowhead breached, annual catches soon began to decline faster than previously, and the trade again entered a period of retreat.

In 1841 and 1842 the industry reached its lowest level in 37 years when just 15 vessels participated.

Reluctant to give up whaling, the Scots, led by Peterhead, began to make harp seals their principal target.

Professor Sanger said the strategy offered immediate profits and enabled them to continue harvesting the occasional bowhead with its rich financial potential.

By the late 1850s the Jan Mayen harp seal stock had also been lowered to uneconomic levels, at least for sailing vessels.

End of an era

Dundee and Peterhead owners then turned in the late 1850s and early 1860s to more efficient and effective, but significantly more expensive technology in the form of steamers.

“In less than two decades, however, the industry, given its inability, or reluctance, to learn from the lessons of the past, had also decimated the Greenland Sea harp seal stock and the Scots began to participate in the Newfoundland seal fishery en route to their whaling grounds in Baffin Bay,” said Professor Sanger.

“Once again the all too familiar and destructive ‘unregulated exploitation-depletion’ cycle was employed.

“Between 1876 and 1900 12 Dundee steamers made 93 trips out of St John’s, capturing a total of 1,156,639 harp seals, contributing appreciably to the decline of the Newfoundland trade.

“The Scots turned to other Arctic activities besides sealing to extend bowhead whaling such as the development of over-winter and land-station whaling at Cumberland Gulf by Captain William Penny, Aberdeen, in 1853.

“A small number also half-heartedly pursued bottle-nosed and white whales while others combined small-scale ‘adventure’ bowhead hunting with indigenous bartering.”

These initiatives, however, simply delayed the pace of decline during the second half of the 19th century.

Only a handful of ships cleared from north-east ports between 1900 and 1914.

World War One effectively brought Scotland’s bloody whale odyssey to a close.

Altogether, the blubber and bone of almost 20,000 bowheads and more than four million harp seals was brought back home for processing, mostly in ports located on Scotland’s east coast.

More like this:

The Terror 2? Dundee actor to reprise role on Franklin’s doomed ship

Scotland’s whaling history: The story of a student’s labour of love

The ‘deadly lakes’ which brought The Big Stink and death and disease to Dundee