Staff of a hardware store in Forres High Street spend quite a bit of time retrieving lost customers and guiding people around its warren of show rooms.

107-111 High Street has been home to Wrights Home Hardware for the past six years, carrying on a long tradition of use of the building as an ironmongers.

It’s a deep, three-storey building with many rambling corridors, easy to lose your bearings.

But why the exquisite and well-preserved cornicing and plasterwork on the upper floor, and the impressive cantilevered staircase with its decorative banisters?

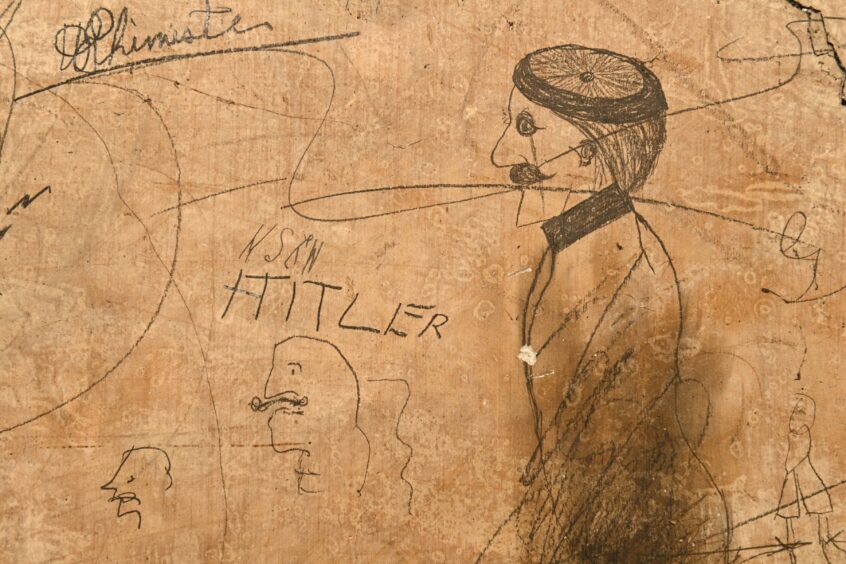

And why are the attic walls full of intriguing graffiti by soldiers?

The building’s 200-year-old history has been uncovered by buildings archaeologist Susan Brook after she was commissioned to carry out a survey of the property by Highland Archaeology Services.

As a self-confessed research-aholic, she returned to the building recently to revisit its intriguing features- and found the staff celebrating the building’s 200th anniversary, appropriately clad for the occasion.

Manager Colin Shreenan explained: “The actual date was last year, and we intended to celebrate it then but couldn’t due to the pandemic, so we’re celebrating it this year.”

Colin and his cheerful staff of 13 admit to being intrigued by the building’s quirks and idiosyncrasies, from the huge copper padlock that would have hung on the frontage to indicate the shop’s purpose, to the cobwebby attic full of graffiti where some employees have added their signatures in an unspoken tradition dating back more than 130 years.

The first clue to the building’s history is the original sign on the frontage, ‘John Cummings 1820’.

Susan said: “He bought the land where 107-111 now stands as early as 1808, but the present buildings were not constructed until around 1820, as Wood’s map of 1823 shows.

“Its first function was as the British Linen Company’s Bank, the bank on the ground floor and the upper floors made into a very grand house indeed.”

She has unearthed a newspaper cutting from January 1847 advising that the property was available for rent, and giving some indication of its grandeur.

Large and Commodious DWELLING HOUSE on HIGH STREET, built and long occupied by the deceased John Cumming banker in Forres, now by Mrs Colonel Grant of Auchernick.

The first floor (exclusive of a large sunk cellar below it) contains kitchen and servants’ room.

The second contains Dining Room and Drawing room of large dimensions, Breakfast Parlour, Pantry and large Bedroom.

The third floor contains three large bedrooms with fire places, and two smaller ones without fire places and in the attics there are two large garrets.

‘Fixed circular sideboard’

In the dining room there is a fixed circular sideboard; and in the drawing room there is a beautiful oil lustre.

There are water closets in the two principal bedrooms, as well as a water closet in the third floor, with a bath and other conveniences.

There is outside accommodation, consisting of coal cellar, wash house and laundry. The garden is well stocked with fruit trees, bushes etc. and surrounded by a high wall. If required the tenant maybe accommodated with a stable and gig house.

Over the years the building has been altered and many of the original features have been lost, but the dazzling decorative plasterwork and curved walls remain in the dining room and drawing room.

It’s thought architect John Paterson of Edinburgh may have been behind the building’s design, with his trademark curved rooms and ‘rock-faced rustication’ at the front of the building, something common in Edinburgh, but not Moray.

The British Linen Company’s Bank time at 107 High Street ended in 1839 when it moved to a much grander building across the road.

As an area suitable for growing flax for linen, Forres was the site of one of the first branches of the British Linen Bank, and one of its oldest.

There is no record of any other bank operating in the north of Scotland at this time, so its customers were drawn from far and wide, from Inverness to Aviemore.

Susan discovered 107 High Street’s grandeur faded after the bank moved out, and the building was split into at least three properties in the late 19th/early 20th Century, occupied by various trades and shops.

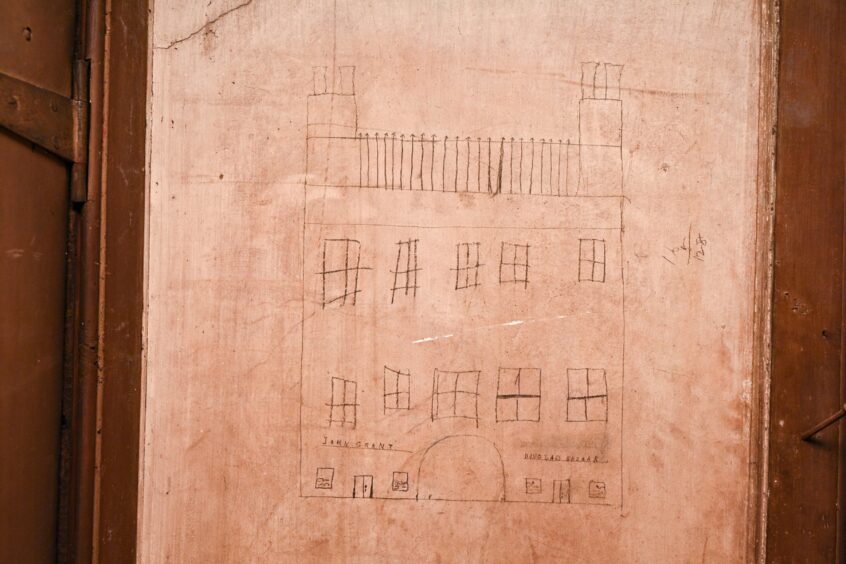

But why would someone sketch a picture of the building more than 100 years ago on the attic wall?

There’s no easy answer to that, but Susan discovered the sketch among much other graffiti in the attic, and describes the find as a building archaeologist’s dream, indicating who the occupants were at the time.

“The drawing is naïve in style, but clearly shows the signage above the shop frontages.

“To the western side reads ‘John Grant’ whilst over the eastern windows it says ‘Douglas’s Bazaar.’”

She established that John Grant died in 1940, his obituaries noting he was a popular resident in Forres who had been a draper for 47 years and had built up his business in the buildings on the High Street from a young age.

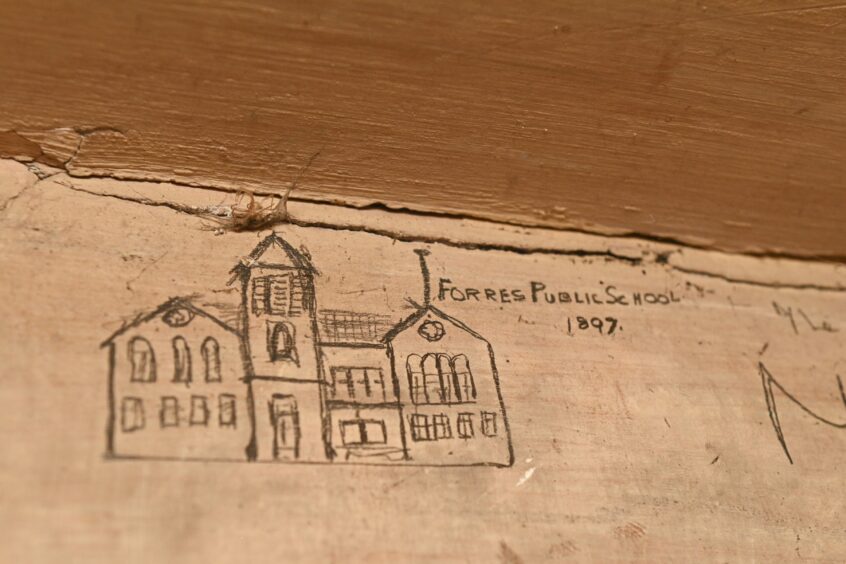

The latter-day graffiti artists also felt compelled to draw other local buildings, including Forres public school, which Susan says is remarkably accurate.

She said: “The building was demolished in the 1970s and replaced by a community centre.

“Whoever sketched it in 1897 did so from memory as you wouldn’t have been able to see the school from the windows.

“Even if you attended that school, it’s a pretty good depiction.”

Scribbles and sketches

There many other scribbles and sketches of buildings and bridges on the walls, including an impressive one of the Tolbooth, and one of a Georgian building with a fanlight which Susan has yet to identify.

She said: “It’s hard to know why people drew pictures of buildings as graffiti in times gone by. It’s not something you imagine contemporary people doing so much.”

The attics were used as military billets in both world wars.

Susan has followed up some of the clues in the graffiti they left behind – and opened up up a Pandora’s box of mysteries.

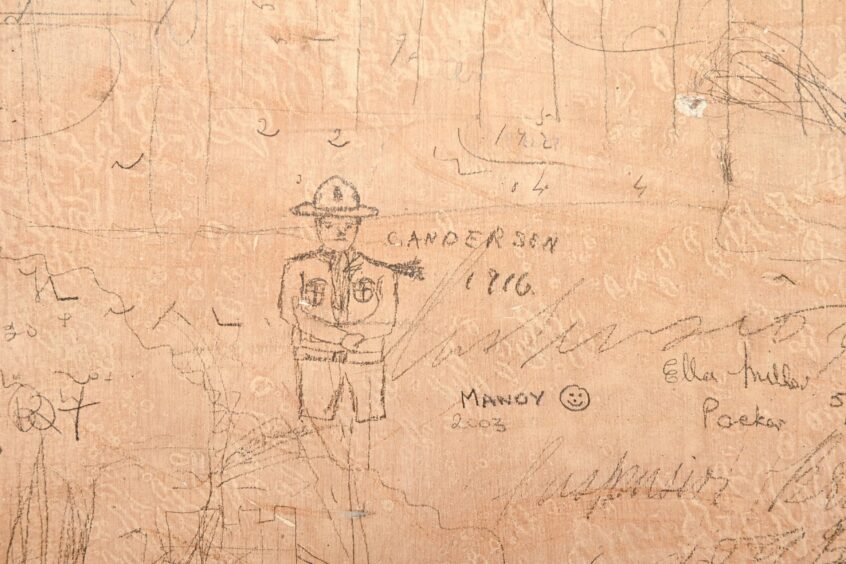

A sketch by C. Andersen, dated 1916, caught her eye as it resembled a Canadian mountie.

She followed up with the Highlanders Museum in Fort George and established there were indeed Canadians based in Forres during both world wars.

“They were from the Canadian Forestry Corps, brought over to work on getting timber from the local forests to supply the war effort.”

But Susan is also considering the possibility that the drawing is of a boy scout, which would explain the flying tassel on the shoulder, a feature of the uniform of the time.

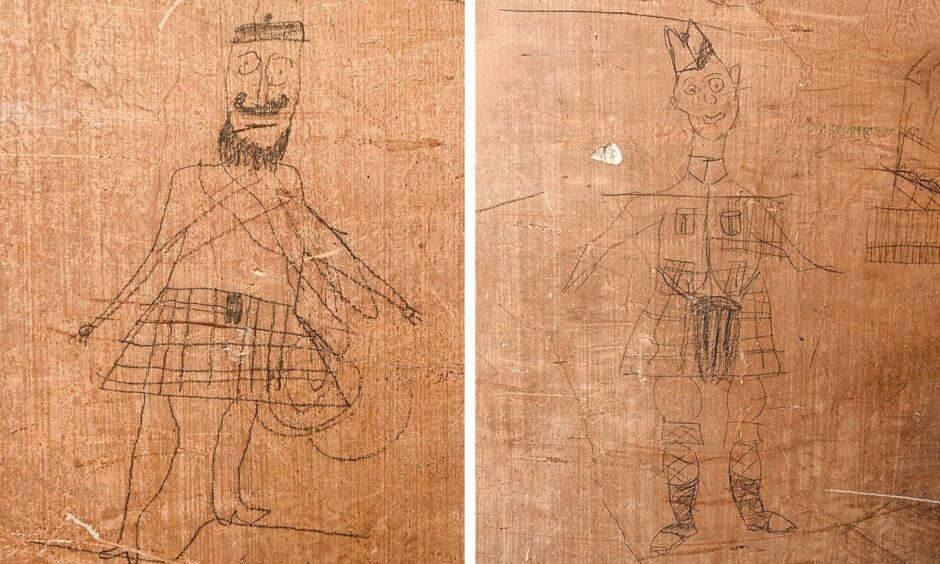

Many other soldiers passed through the attics during the wars, leaving sketches to prove it.

Details in their attire identify their regiment- with the checked stripe on the Glengarry (image above right) shows a Queen’s Own Seaforth Highlander.

Is the left-hand image a Queen’s Own Cameron Highlander, with the flatter cap?

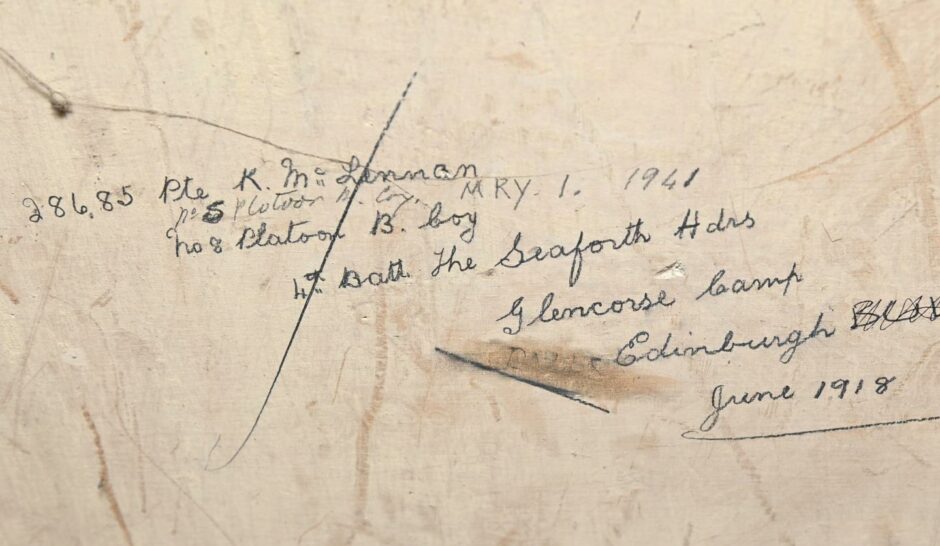

Particularly intriguing is a strange scribble by a K. McLennan, dated 1918.

But Susan traced the number next to Pte McLennan’s name, and found it belonged to a soldier by the unlikely name of ‘Tommy Trench’.

And on cross-referencing the date, she saw that 4th Batt The Seaforth Highlanders would have been in France in 1918.

Glencorse camp refers to an army training camp near Penicuik.

It’s quite a mystery- but undaunted, Susan researched on.

She has found a newspaper cutting from 1972 celebrating the golden wedding anniversary of a Mr and Mrs K McLennan of 88 High Street, Forres.

Missing link?

A bit of a stretch to link with the graffiti maybe? Not so much, as it turns out Kenneth McLennan worked at Mackenzie and Cruickshank, ironmongers, for 33 years.

And Mackenzie & Cruickshank’s shop was at 107-111 High Street Forres, where Wright’s Home Hardware is now.

If it was that particular K McLennan, he would have been 18 in 1918, the right age to be called up for training at Glencorse.

Susan said: “If any readers can help identifying anything or anyone in any of the graffiti, I’d be delighted.”

One thing’s for sure- 107-111 High Street Forres is a time capsule with plenty more secrets to yield.