A dense mass of people stood in silence to hear the names of the dead.

Reverend Alexander Caseby appeared from the Valleyfield Colliery office and began to read from the piece of paper in his shaking hand.

One girl, expecting her first baby, fell at his feet when her husband’s name was called.

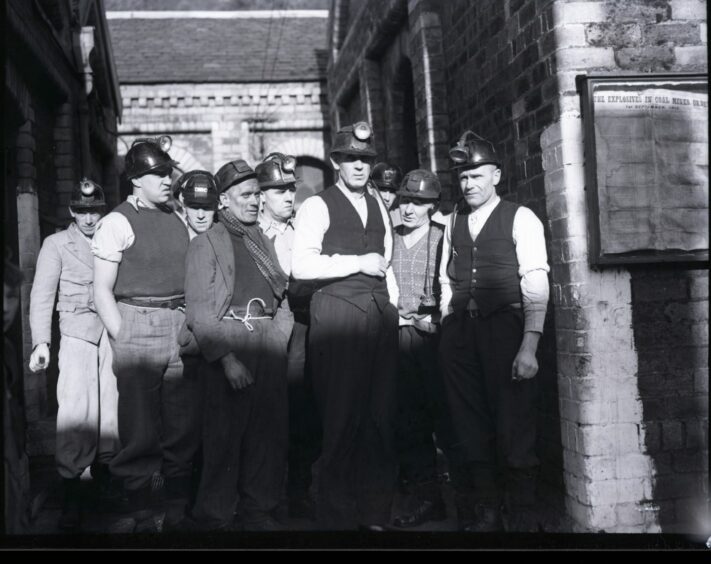

The Valleyfield Colliery at Newmills was one of a group of 14 collieries owned by the Fife Coal Company where the output was about 850 tons per day.

It was the scene of one of Fife’s worst mining disasters on October 28 1939, claiming 35 lives and leaving 42 children without a dad.

An ignition of firedamp and coal dust caused a devastating explosion and most of the men who died came from the villages of Low and High Valleyfield.

Rev Caseby’s son, Cyril was nine when the colliery crisis whistle sounded at 4am and brought tragedy to a village already facing the realities of war.

“All of sudden, things were to get worse, which was not war-related,” he said.

“Early in the morning of Saturday October 28 1939 we were awakened by the continuous sound of Valleyfield Colliery steam whistle.

“Normally it only blew in short blasts at the start and end of shifts.

“A heavy knock then came to our door, our dad answered, got dressed and left immediately.

“All our mum knew was that there had been an incident at the colliery and he was required there quickly.”

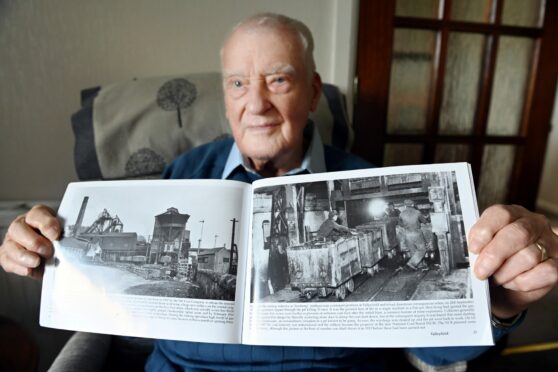

Aberdeen man Cyril, now 91, said the Caseby children were made to go back to bed.

He recalled: “After breakfast, at the first opportunity, we walked down the railway line to the colliery, assuming that it been bombed.

“On arriving, we found ourselves among a growing crowd.

“Many were standing about quietly whilst others from the emergency services seemed almost frantic.

“We quickly learned that there had been no bombing but instead an accident underground.

“The loved ones of the miners working that night were all gathering to get news.

“There were many mothers, some with shawls or blankets round them, holding babies in their arms with their older children clinging to her by her side.

“I could see some of my school classmates there.

“I was confused and full of mixed emotions and did not want to be there and kept looking for my dad.”

Cyril said his older twin brothers, Sandy and Grant, kept wandering off and he was left standing beside a building near the colliery’s main entrance.

“Then there was a hush when our dad appeared, climbed up the stairs towards the pit head and stopped,” said Cyril.

“We moved with the crowd to be near the front but he did not appear to see us.

“He had a piece of paper in his shaking hand and said in a nervous voice that there had been an explosion in a certain section of the underground workings and that it was feared that the people working there would not have survived.

“He then began to read slowly from the list of 35 names.

“Some names were familiar and some not.

“Soon there were gasps and grown-ups and children sobbing, then one lady nearby fainted.

“The atmosphere became so charged with emotions I wanted to go home but my brothers wanted to stay.

“Then our father paused as he was about to read the next name.

“It was Robert McFarlane.

“He was one of his church elders, a good friend of his, and well-liked throughout the community.

“His daughter was Jenny, the same age as our sister.

“She was always in our house and became just like another sister to us.

“Now her dad was dead.”

Everything went quiet

Cyril became overwhelmed.

He made his way through the crowd and went back home.

“My mother was anxious, having already heard the news, and wanted to know about dad and the twins,” he recalled.

“I gave her what news I had and as my sister Margaret was at the shops, I left it to my mum to tell her about Jenny’s dad.

“The twins returned later and said that they had been delayed as there was aircraft activity with gunfire overhead at the colliery after I left and that everyone was instructed to take cover.

“When everything went quiet, they ran home.

“Dad arrived home in early afternoon drained by the experience and we thought he would not be fit for the church service the following day but he managed.”

The tragedy devastated the close-knit community and came just eight years after 10 men had perished due to carbon monoxide poisoning at Bowhill pit.

King George V and the prime minister sent messages of condolence and the manager of the colliery and agent of the coal company were later prosecuted and fined.

The colliery would continue to play a prominent part in the lives of the Caseby family and Cyril got a job preparing the wage sheets at the pit in 1946.

“The transition of the collieries from private to public ownership was well advanced when I was given my first chance to go underground,” he said.

“The smell, dampness, noise, dust and lighting added a new dimension.

“The further you went into the working face, it all seemed to get smaller and claustrophobic with the noise intensifying.

“In addition to the machinery noise, there was rumbling overhead and you could hear the timber pit props creaking.

“I enjoyed it but was glad to be out again.

“My respect for the people who chose this for a profession rose enormously.”

Reverend Caseby was fully ordained as a Church of Scotland minister in 1946, which coincided with the amalgamation of the Torryburn and Newmills churches.

The family moved to West Lothian but Cyril returned to Valleyfield to mark the 50th anniversary of the pit disaster in 1989 with his wife, Gladys.

He said: “The abbey was packed with many people who were involved at the time, along with the relatives of those who died.

“I thought that it would be a sombre occasion but the popular hymn singing was uplifting with the service moving and a fitting tribute to all who did so much on the day.

“The 35 names were read again in the same order as my father did at the time.

“We were then invited to the Miners Welfare Institute in High Valleyfield for refreshments where we made ourselves known and chatted to some of the older people.

“It was there that I saw for the first time the memorial statue.”

The memorial, which depicts a wife, surrounded by her children, waiting for her husband to come home, was erected on the 50th anniversary of the tragedy.

It remains a focal point for remembrance services.

Cyril said: “The sculptor had captured the moment and all at once I found myself standing there 50 years ago and all the mixed emotions suddenly came back.”

You might also like:

Coal Country: The stories behind Fife’s lost mines and the flood of Longannet