Every year we dutifully “spring forward and fall back” as the clocks change – an idea first pioneered by an ancestor of Coldplay frontman Chris Martin.

This weekend, the clocks go back an hour marking the end of British Summer Time as the nights draw in for winter.

At 2am on Sunday October 31, the clocks will revert to Greenwich Mean Time, with daylight saving over for another year.

The annual ritual means a delightful extra hour in bed for those who aren’t shift workers – or the parents of small children who will be awake early regardless.

Why do we put the clocks forward?

Often seen as an eccentric British tradition, the changing of clocks is a practice to maximise daylight hours.

The idea dates back more than 100 years – a phenomenon initially pioneered by Chris Martin of Coldplay’s ancestor.

In the 1900s, Kent builder William Willett noticed that when he was up and about early in the morning, many curtains were still drawn.

Britain ran on Greenwich Mean Time all year round meaning it was light at 3am and dark at 9pm during summer.

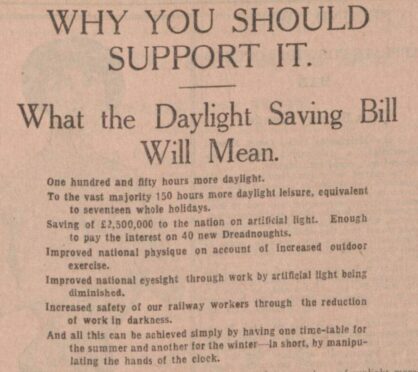

Mr Willett campaigned relentlessly for clocks to go forward in spring to increase the amount of daylight for the benefits of health and recreation.

He was the great-great-grandfather of Coldplay frontman Chris Martin, who wrote songs ‘Clocks’ and ‘Daylight’ – although it is unclear if these were inspired by his tenacious ancestor.

Willett’s campaign ‘The Waste of Daylight’ made it as far as the House of Commons, but despite widespread support, was unsuccessful.

Such was the support for the idea in Dundee, that in 1911, many firms altered summer working hours to provide employees with more time to enjoy daylight.

Shifts started at 8am instead of 9am and therefore finished earlier – a move backed by then Dundee MP Winston Churchill.

In 1916 – ironically a year after Willet’s death – the practice of changing the clocks was introduced nationwide, but for the benefits of war, not health.

During the First World War, Germany put the clocks forward in spring to increase daylight – and workers’ productivity.

Britain quickly followed suit seeing it as a solution to a coal shortage, and the Summer Time Act was passed on May 17 1916.

Putting the clocks back

To maximise daylight again in winter, the clocks go back an hour to GMT making the winter mornings lighter and brighter.

The reason clocks go back in the early hours of the morning is to cause the least disruption – something railway firms insisted upon.

It was felt that putting clocks back at any other time of day would cause untold chaos for timetabling and the running of trains.

In Scotland, where the sun rises later, the lighter winter mornings brought important benefits.

If the clocks didn’t revert back, farmers would be forced to work in the dark for several hours, and schoolchildren would face dangerous, dark walks to school.

Unfortunately, changing the clocks does nothing for the seasonal temperatures.

In 1916 as the change was implemented, one reader wrote to the Press and Journal joking: “Can’t Parliament do something to send the thermometer up in the chilly weather?”

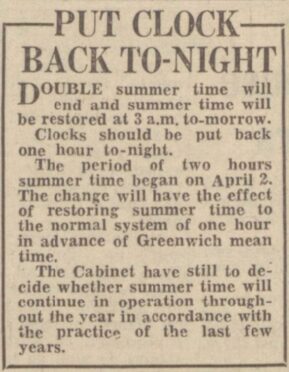

When the clocks went forward by two hours

As you enjoy an extra hour in bed this weekend, spare a thought for those living in wartime Britain.

In 1941, clocks were ahead of GMT by two hours in what was known as British Double Summer Time.

The decision had been taken in autumn 1940 not to put the clocks back, meaning when they went forward the following spring they were two hours ahead.

It was seen as an energy-saving move and the extra daylight in the evening also gave people longer to get home safely during the blackout.

Britain reverted back to the one-hour difference when war ended, but double daylight saving was reintroduced in the summer of 1947 after fuel shortages the previous winter.

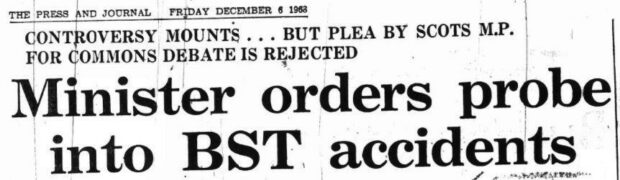

Parliament played with time zones again in the late 1960s when, as an experiment, Harold Wilson’s government adopted British Standard Time.

This meant clocks were put forward in spring 1968 but not put back that autumn.

To counteract the darker winter mornings, a number of rural primary schools in Aberdeenshire and Moray started their school day at 10am.

And the then rector of The Gordon Schools Huntly pleaded for better lighting in the town for pupils arriving at school in hours of darkness.

The experiment was eventually ended in 1971 when it was deemed inconclusive as to whether it brought any benefit to Brits or not.