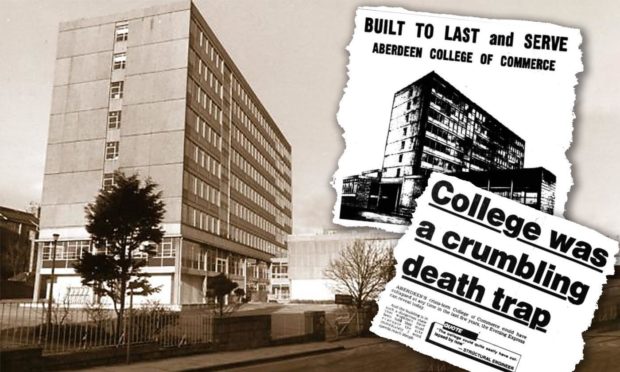

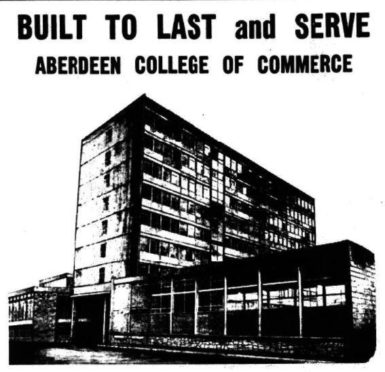

When Aberdeen’s new College of Commerce was constructed using the latest technology in 1965, it was proclaimed that this building of the future was “built to last and serve”.

But little over 20 years later the building was condemned, with structural engineers fearing it was in danger of collapsing at any time.

The modern building was proposed in the early 1960s to house the Commercial College, which was outgrowing its various borrowed city centre premises.

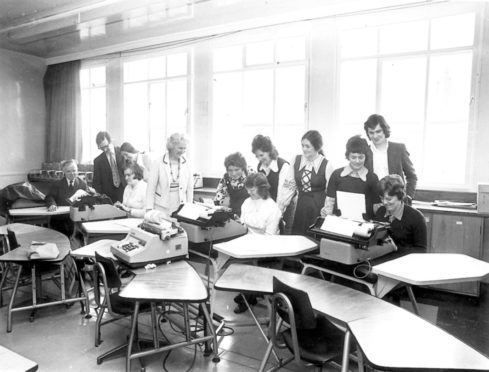

Founded in 1959, the Commercial College offered full-time secretarial courses to girls, business studies to boys and part-time courses to students working in shops, offices and the Civil Service.

The vocational courses proved popular, and to meet growing demand, the college and its hundreds of students were dispersed throughout buildings in the city.

Scholars crammed into premises including St Clement’s School, East St Clement’s Church, West St Clement’s Church, Commerce Street School, Marywell Street School and St Katherine’s Community Centre.

But enough was enough – it was felt the college and students should be together under one roof.

The site of the closed Holburn Street School was identified as the best place for a new state-of-the-art education facility and the Victorian school was duly knocked down in 1963.

College constructed in record time

People were stunned at the rate the building soared above the city skyline on the two-acre site between Holburn Street and the Hardgate.

The foundations were laid in February 1964, and by summer 1965, the nine-storey brutalist block was nearing completion.

The speed of the construction was attributed to a new, industrialised building technique which used precast panels and slabs, with dressed granite gables.

This reduced the need for on-site concrete work, speeding up production.

The £745,000 build included classrooms, administrative rooms, a library and a cutting-edge language laboratory with private booths for listening and recording to learn foreign languages.

Other bespoke features were a recording studio, a printing room and a model office where students could learn “office procedure” like operating switchboards and filing systems.

While “specialist rooms” were dedicated to retail distribution with window displays, groceries, hardware and a supermarket layout.

There was a large gymnasium and canteen on the ground floor with a 60ft-long common room above.

And there was even penthouse accommodation for an on-site janitor consisting of a living room, three bedrooms, a kitchen and bathroom.

Future bright for college

Principal Mr Bernard Edwards and his team of 82 full-time and 200 part-time evening class teachers welcomed 700 of the college’s 3,500 students on August 30 1965.

The college partially opened with its first five floors completed, but some students remained in temporary accommodation elsewhere until the build was complete.

It would be more than a year later before the College of Commerce was fully operational and officially opened by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother on October 18 1966.

Ahead of the visit, the new building was described in the Press and Journal as “one of the city’s most striking, though perhaps not most beautiful landmarks”.

But it was said the college offered a “fuller and more enjoyable education, and they help the students to become students and not just elderly schoolchildren”.

As well as lessons there were clubs and societies, sports teams, art exhibitions and drama productions.

It was the days before the oil boom and Aberdeen was a low-wage city – but the college offered opportunities.

However, there were concerns employers weren’t supporting students in releasing them from their jobs for a day’s study.

A report said: “Local firms are, on the whole, unwilling to release trainees during working hours to go to the College of Commerce.

“Industry and commerce are not expanding at anything like the same rate [as other cities], and consequently more and more are leaving the city and taking up jobs elsewhere.

“Aberdeen is a low-wage city and young people who have qualifications from the College of Commerce can get jobs that are far better paid and have better prospects down south.

“There have been instances of girls with secretarial and language qualifications being offered up to three times more in jobs in London than they could earn in Aberdeen.”

The College of Commerce made Aberdeen a progressive city that invested in its youth, and commentators said “its future was bright”.

Happy times and hijinks

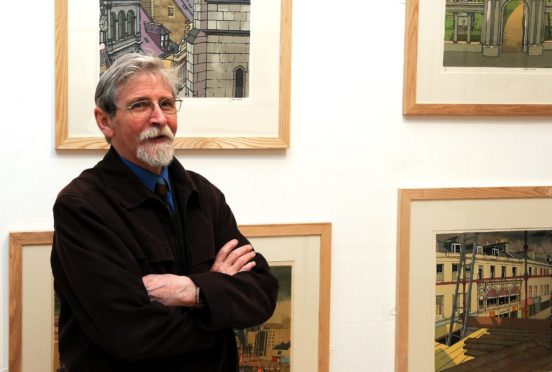

Practical, creative subjects also found a home at the College of Commerce with music and drama departments, and the art department where legendary Aberdeen artist Jimmy Furneaux was a tutor.

Mr Furneaux was a memorable man for many a former student of the college – which he referred to as the College of Comedy – with his keen eye and wicked sense of humor.

He would purposely patrol the art department, sweeping through studios in his artist’s smock with unkempt hair.

Described by former students as a “raconteur” after his death in 2013, there are many tales of happy times and hijinks from the college’s art department.

In the 1970s, the art department made its mark in more ways than one, when a student dribbled a small amount of screen printing ink from a top floor window of the college.

When it rained, the ink spread down the outside of the building.

The college continued at the forefront of education and in the mid-70s, the national president of the British Computer Society, Graham Morris, visited the institution.

He lectured data processing students, but wrongly predicted that there would not be a great need for “computer professionals” in the future believing computers would operate themselves.

But the 1970s also brought unrest and students weren’t afraid to make their voices heard.

Unhappy with classroom conditions, students protested in 1974 citing a number of safety concerns relating to the building, as well as the fire alarm system and poor heating.

But these were largely dismissed.

And hundreds of students boycotted lectures in 1976 in a protest the government’s planned cuts in education.

Students also used their voices for a good cause – raising money for local charities.

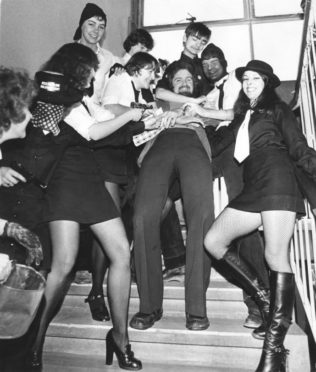

Scholars hit the headlines in 1979 when they staged the kidnap of marketing lecturer Jim Garden, dragging him down the college’s stairwells before bundling him into a van.

An anonymous note was left in a staffroom demanding a hefty ransom, and students broke into classrooms and staffrooms with charity cans demanding cash to release Mr Garden from a flat in Union Grove.

Cracks appeared in classrooms

The 1980s saw change at the college when principal Mr Edwards retired in 1982, he was presented with a portrait of himself at a leaving do at the Amatola hotel.

There were more celebrations in 1984 when the College of Commerce marked its 25th anniversary.

Staff held a cheese and wine party to raise a glass to the quarter century milestone.

A change in education and curricula across Britain saw less emphasis on vocational subjects with a shift towards encouraging schoolchildren into universities.

O-Grades were replaced with Standard Grades in 1986 and there were attempts by the Conservative government in Westminster to phase out comprehensive education altogether in Scotland.

But there were far bigger concerns at the college in 1986 than the Thatcher government’s education reforms.

Cracks were literally appearing in the building.

Previous concerns saw the uppermost floor out of bounds, but staff raised new fears about the condition of the building and structural engineers were brought in.

Classroom walls were cracking and engineers found that the metal reinforcements in the blocks the building was constructed from were corroded.

In 1987 investigations continued and workmen were tasked with abseiling down the outside of the building to check the exterior.

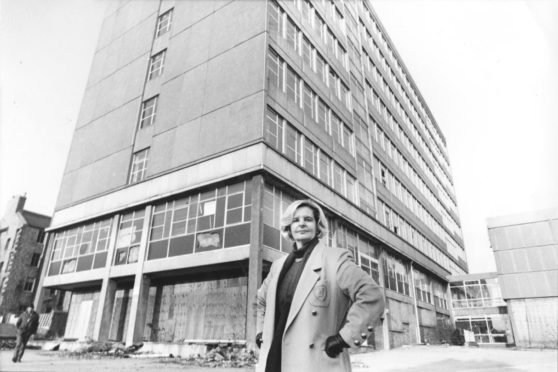

In-depth finds made for grim reading, the building was evacuated “almost overnight” and closed in November that year.

‘College was crumbling death trap’

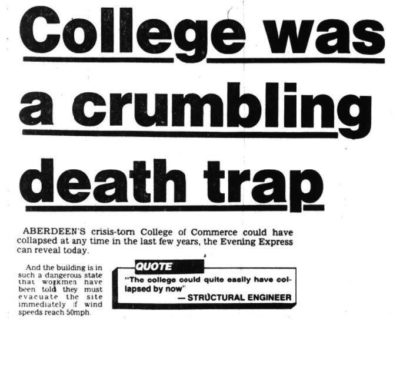

A report released in 1988 costing £65,000 revealed that the building “could have collapsed at any time” in previous years.

And workmen on the site were advised to evacuate the premises if windspeeds reached 50mph.

Testing showed that parts of the 22-year old building were “severely overstressed” with structural engineers claiming to be “astonished the building was still standing”.

Inspections found the problems were caused by a combination of construction and design faults.

Concrete cast did not compact properly and in turn allowed exposed metal to corrode.

Walter Scott, director of the council’s architectural services at time, said: “The building now contains an unacceptable degree of risk.

“It is conceivable wall panels could be sucked off by hurricane-force winds”.

It was also revealed that an investigation had been carried out as early as 1979 surveying main floor spans, corridors, wind loading and heated ceilings.

The protesting students of the 1970s were finally vindicated.

Speaking in 1987, retired principal Mr Edwards said he had never been shown the outcome of the report, but added: “I know it showed certain defects.

“At the college we always felt a greater investigation should have been carried out.

“There were faults before I left which caused considerable disquiet, but we were assured there was no danger.”

English teacher Mr Dunsmuir, who had taught at the College of Commerce for 16 years, said cracks had appeared in interior classroom walls that were “big enough to put your hand into”.

While another staff member said cracks were “repaired” by stuffing paper into them.

‘Building must be demolished’

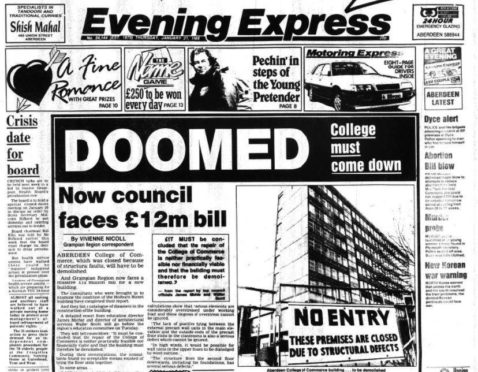

The council’s architectural services’ report found serious defects and that “no acceptable means existed of tying floor units together”.

While “vital ties holding the building together did not conform with drawings” and “reinforcing ties were not properly bent out from the wall units and offered no tie”.

Essential cement grouting was found to be missing, and storey height columns were “inadequately reinforced”.

With the prospect of a £12 million repair bill, the report put to councillors concluded: “The repair of the College of Commerce is neither practically feasible nor financially viable and the building must therefore be demolished.”

But the empty, eyesore building was still standing in 1990, much to the disdain of city councillors.

A legal wrangle had arisen over conflicting engineers’ reports and it was feared the College of Commerce saga would end up in court.

Ironically, it would be another nine years before the condemned blot on the landscape was finally flattened and in its place, energy company headquarters Talisman House was erected.

Despite its relatively short existence, Aberdeen College of Commerce was considered an esteemed and forward-thinking seat of learning in Scotland.

The College of Commerce amalgamated with Aberdeen Technical College and Clinterty Agricultural College to form Aberdeen College where scholars of all ages continue to broaden their horizons.

See more like this: