Many people will fondly remember the palatial post office headquarters on Aberdeen’s Crown Street – one of the city’s centre’s finest buildings.

But before the sophisticated and automated systems in use today, post was a lot slower in reaching Aberdeen.

During the 1700s, it took three days for mail to get to Edinburgh from Aberdeen’s post office on Shiprow via courier.

But the introduction of a mail coach in 1778 – nicknamed The Fly – sped up the process slightly to a mere 32-hour delivery time.

The improvement of roads, and additional stops with fresh relays of horses available, saw a huge advance in the efficiency of Aberdeen’s postal system.

A new time record was set on July 31 1798 when four horses were dispatched with a coach at 9pm in Edinburgh, arriving in Aberdeen at 6am the next morning.

And by 1811, daily postal and passenger services were running from Dempster’s Hotel on Union Street in Aberdeen to Inverness.

In 1818, four postmen were employed to cover Aberdeen and district, but they weren’t paid by the post office – instead they were paid by those who received the letters.

The growing postal economy saw the location of Aberdeen’s post office – and postmaster Alexander Dingwall – move from various premises in Netherkirkgate to Castle Street, to 40 Union Street and back to Netherkirkgate.

Aberdeen’s first standalone post office opened on Market Street in 1841, and the penny post and adhesive stamps – invented by James Chalmers of Dundee – were brought to the masses.

Aberdonians were also encouraged to “cut slits in doors” – letterboxes – for the delivery of mail.

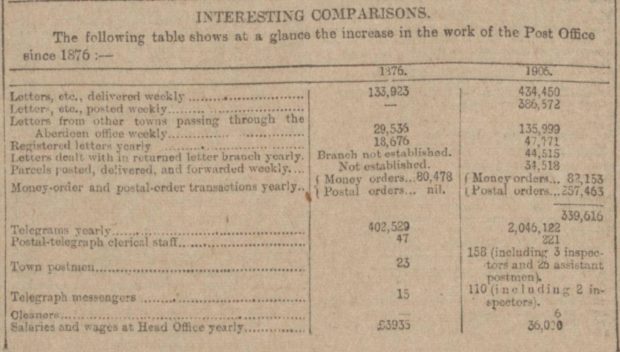

By 1850, 27,000 letters were delivered weekly in Aberdeen, the city had a number of sub-post offices and, within a decade, mail trains replaced mail coaches.

In the late 1800s another site at the bottom of Market Street was acquired to establish a bigger post office to keep up with demand, but even this was not adequate.

Postmen were having to sort mail in their Shiprow apartments, and a building that could meet the demands of telegraph was needed.

Grand opening

The post office struggled to find a site big enough that was still near the station, harbour and city centre.

But a stretch of housing was identified between Crown Street and Dee Street – and duly demolished.

And in 1907, after five-and-a-half years of construction, a grand new post office with towers, battlements, parapets, stepped gables and gargoyles was unveiled.

The £50,000 three-storey structure, built from dressed Kemnay and Rubislaw granite, featured an ornate entrance on Crown Street.

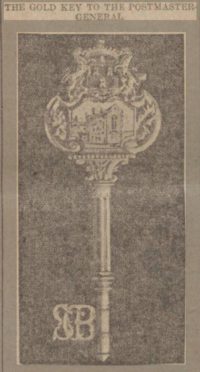

Upon the occasion of its opening, Britain’s postmaster-general Sydney C Buxton, an MP, was presented with a gold key.

Handmade by city jewellers James Hardy and Co, it featured an enameled view of the building, his initials and the city motto ‘Bon Accord’.

The inside of the post office was befitting of the exterior grandeur, and the pomp and circumstance of its opening ceremony.

A 50ft long public office had marble-lined walls, marble pillars that reached up to a lofty ceiling, and underfoot, there was exquisite mosaic flooring.

As well as electric lighting and electric lifts, there was a telephone office where the public could make calls to other towns and cities.

And, unlike the cramped Shiprow flats, the sorting room could accommodate 90 postmen at once who sat at large mahogany tables with attached seating.

There was even a raised superintendents’ room with a glass frontage where the official had “an unobstructed view of men employed under him”.

The telegraph instrument room featured the latest technology: telegrams were sent down a pneumatic tube which would discharge onto a counter.

Telegram boys waited patiently for their messages and were handed a token of a certain value along with each telegram.

At the end of the day the tokens were handed back in, the total determining how much each boy would earn daily.

Meanwhile a cycle room had a mechanic employed to service the bikes constantly in use by postmen and telegram messengers.

First-class facilities

The post office was built with the welfare of its workforce in mind.

A popular facility was the first floor dining club, a large-scale canteen which provided postal staff with government-subsidised hot meals.

There was a recreation room for messenger boys when off duty and in pre-NHS days there was even an on-site medical office where a doctor was available to employees.

The postmaster’s room was not the biggest or grandest, but contained the ‘master clock’.

In an industry where timing and efficiency was king, the master clock regulated all the other clocks in the building.

The second floor housed the telegraph school, where male and female learners were taught the intricacies of operating telegraph instruments, switchboards and transcribing morse scripts.

A busy communication headquarters, The Great Northern Company’s telegraph cables were laid from Norway to Peterhead and on to the Crown Street Post Office.

Over the North Sea cables, messages were sent from Aberdeen to Russia, Romania, China, the Philippines, New Zealand and beyond.

By the time the Crown Street Post Office opened, Aberdeen was handling more than 2,000,000 telegrams a year.

War and peace

Just a few years later, the post office made the headlines when it was targeted by suffragettes.

On June 29 1912, a co-ordinated attack on post offices across the country was launched by women campaigning for equal voting rights.

Branches in London, Manchester, Edinburgh and Dundee were among dozens hit.

At Crown Street Post Office, two large windows by the main entrance were smashed.

Two small hammers with inscriptions attached demanding the release of imprisoned suffragists and ‘Votes for Women’ were found at the scene.

As the years rolled on, the post office was busier than ever when war broke out in 1914.

Every male employee of the Post Office was sent a letter encouraging him to enlist, and by December that year 28,000 staff had signed up across Britain.

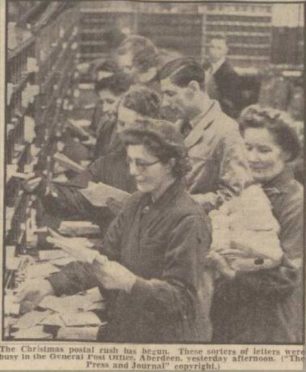

Women were drafted in to fill the vacancies left behind, and in Aberdeen teenage schoolboys were employed too, to cope with the increasing demand on services.

During the conflict around 12 million letters a week were delivered to soldiers, many on the front line.

But in return, many families received devastating telegrams informing them that their sons would never come home.

In the post-war years, the post office continued to go from strength to strength.

In 1938, a pioneering ‘mobile post office’ – in the form of a red tractor and trailer – visited Aberdeen.

The idea behind the post office on wheels was that it could be parked at open-air events and people could send letters and postcards home.

But away from the fun and folly of day trips, hard times were just around the corner.

Upon the outbreak of war in 1939, many male members of staff again answered the call for King and Country.

The Crown Street Post Office keenly felt the losses of war once again, with several staff members killed or taken as prisoners of war.

Challenging times ahead

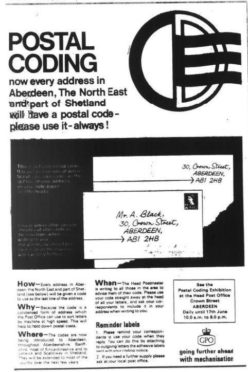

The 1960s also saw a revolution in the postal system in Aberdeen: the introduction of postcodes.

Glasgow had had its own system in place since the 1920s, but Aberdeen was the first city in Scotland to officially roll-out the postcode system in 1967.

But as modern technology progressed, other postal services became outdated.

As most homes had their own phones, there was no longer the same demand for telegrams.

The 1960s saw a significant drop in the number of telegrams sent, and in 1977, the post office decided to drop the service.

They continued for a few years under British Telecom, but the final telegram was sent in the UK in September 1982.

The 1970s and 80s brought their own challenges for the post office.

Britain’s first-ever national postal strike took place in 1971 when workers walked out for seven weeks after demands for a 15-20% pay rise were refused.

Later in the decade, there were more serious concerns.

Sub-post offices became the target of stealthy killer Donald Neilson, nicknamed the ‘black panther’.

Closer to home, there was shock over the murder of New Pitsligo post mistress Dorothy Park in 1981, which to this day remains unsolved.

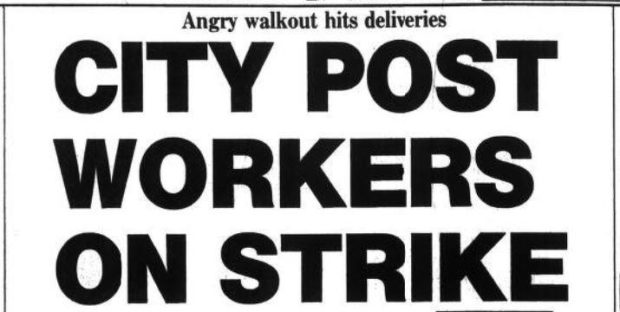

Industrial action returned in the 1980s – in Aberdeen, workers walked out with no warning in a lightning strike on August 7 1986.

More than 400 postal workers stopped virtually all deliveries in Aberdeen, and the wider post office made a plea urging the public not to post any more items that day.

The unofficial 24-hour stoppage was triggered by management’s refusal to allow a mass meeting at 6am.

Staff had previously raised concerns about ‘efficiency measures’ that had been introduced the previous year, the use of casual labour and communications issues.

Angry workers instead marched out of Crown Street Post Office and held their meeting in a nearby car park in the rain.

A series of bitter strikes continued to flare up in Aberdeen over the following weeks causing severe disruption.

Two years later, nationwide industrial action again took place.

Members of the Union of Communication Workers walked out in 1988 to protest bonuses being paid to new recruits in London.

It was the first national postal strike in 17 years and crippled services – Scotland alone had a backlog of 4,000,000 million letters.

Disruption continued in December when staff at Aberdeen’s four main post offices walk out over the closure or downgrading of sub-post office branches.

A new century

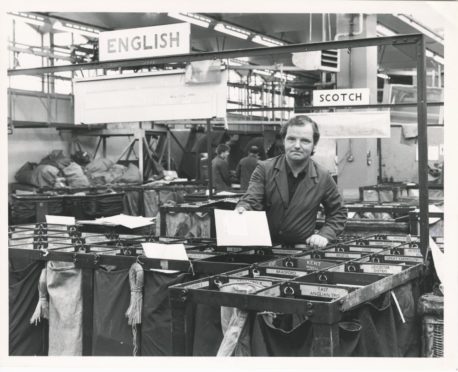

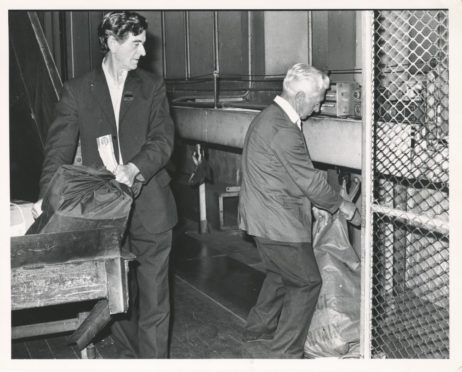

By the 1990s, the day to day role of the post office had radically changed from 1907.

And nearly 90 years after it opened, the listed, Edwardian headquarters on Crown Street was no longer fit for purpose.

An extension had already been added to cope with the introduction of mechanisation, but the building could not cope with growing automation and machinery.

A new £10 million base was built at Altens and staff had vacated Crown Street by October.

At the time, area manager Nicola Scrivings said: “Everyone will look back nostalgically to Crown Street – so many of our staff have spent many years working there.

“The office has a lot of character and history.”

The building was sold for £1.5 million and after years of back and forth, plans were granted to transform the building into 26 flats with a further 64 built on the site of the modern extension.

During the conversion work, old tunnels were unearthed and a vault containing 100 old posties’ bikes was discovered.

The building couldn’t carry the changing post office into the 21st century, but the new development – complete with a residents’ sauna, gym and underground car park – opened in 2001, renamed New Century House.

See more like this: