It began as just another normal day for the pilots and passengers who boarded the Chinook helicopter as the prelude to returning from Shell Expro’s Brent field to Shetland on November 6 1986.

The 47 men – three crew members and 44 passengers – left for their destination at Sumburgh and everything seemed to be progressing smoothly as they ventured towards their destination.

Yet what had seemed like a routine trip rapidly turned into a “Flight to Disaster”, the headline on the front page of the next day’s Press & Journal.

The British International Helicopters Chinook was on its usual approach and the pilot even made his standard “two minutes to landing” call as it descended towards the runway at a height of 500 feet.

But then, suddenly, and with catastrophic speed, the aircraft disappeared from the radar screens in the airport control tower.

The crew on the doomed helicopter did not even have time to send a distress signal before it plummeted into the North Sea, breaking up on impact and sinking beneath the waves.

And, when the emergency services sped to the scene of the disaster, they found scenes of destruction and mayhem, which eventually yielded a grisly death toll of 45.

Two people, almost incredibly, survived the crash.

The accident occurred when transmission failure caused the twin rotor blades to collide, with the helicopter falling 50 metres to the sea.

Pilot Pushp Vaid and passenger Eric Morrans were the only survivors, with the former smashing through a window to escape the stricken helicopter.

Captain Gordon Mitchell was in charge of the coastguard base at Sumburgh at the time of the tragedy, and his helicopter was first on the scene.

I pray for the souls of the people who left us.”

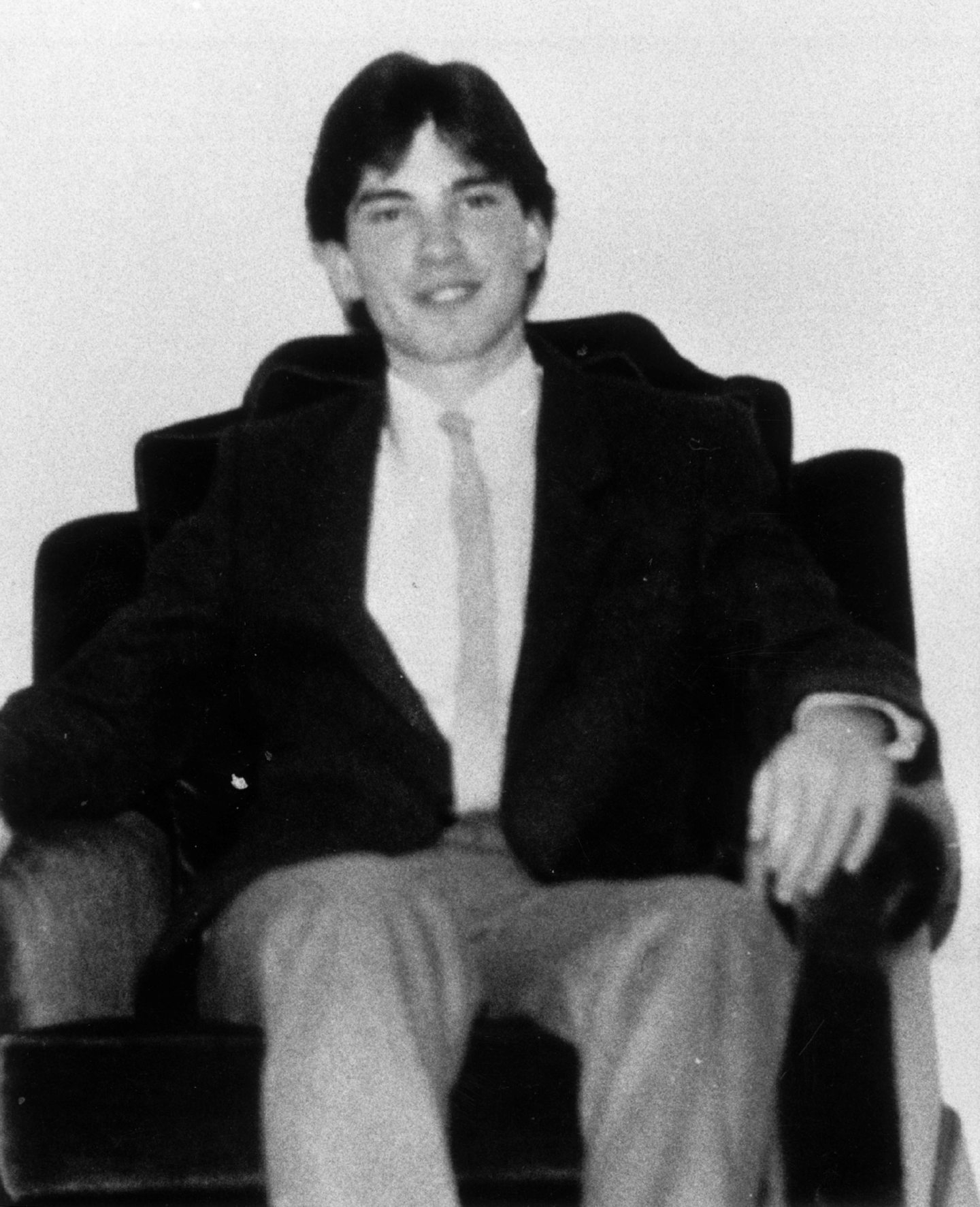

Pilot Pushp Vaid

And while the odds of finding anybody still alive seemed remote at that stage, they located and airlifted Vaid and Morrans from the sea and, in a race against time, flew the two men to Lerwick’s Gilbert Bain Hospital.

As Capt Mitchell later recalled: “We saw wreckage, and then we spotted two survivors. One was hanging on to a dinghy and the other was hanging on to a piece of wreckage.

“We went in and winched them up into the helicopter. It wasn’t difficult conditions for it.”

However, by now, the scale of the devastation had become clear and journalists attended a press conference at Shell’s base in Aberdeen.

But while there was a fresh veil of tears over the industry, which had already suffered a number of fatal air incidents, Joseph Morrans explained how his son had managed to escape from the helicopter.

Speaking at his home in Aberdeen, the relieved 42-year-old, himself an offshore worker, told the Press & Journal: “Eric said that he was sleeping on the Chinook when, apparently, there was a bang and then the helicopter fell.

“The next thing he remembers is being in the water, coming to the surface, and the life raft bobbing up beside him.

“Despite having a broken arm, he still had the presence of mind to entangle himself in the straps around the raft before he fell unconscious. He knew that it would keep him afloat.

“And that’s what saved him – the rescue helicopter pilot saw the (Dayglo) raft and they went down to get him. They just had to cut him from the straps.

“We cannot express how relieved we are that he is alive. But words cannot say anything to the families of those who are still missing.

“It is just dreadful.”

The pain may be more manageable, but there will still be times when the loss is felt deeply by those who lost loved ones.”

Rev Gordon Craig, speaking in 2016

It later emerged that the helicopter was normally based at Aberdeen Airport, but had been at Sumburgh Airport since November 3 to operate a shuttle service from the Brent oilfield in the East Shetland Basin.

On that ill-starred morning of November 6, the first flight was delayed due to an oil leak from an engine gearbox, but that was soon rectified and the aircraft left Sumburgh at 8.58am with 40 passengers on board.

It visited three platforms with exchanges of freight and passengers, then departed from Brent Platform C at 10.22am with 44 passengers on board for return to Sumburgh.

As it approached its destination, it was cleared to descend and the controller granted permission to land on runway 24.

And then… nothing else was heard from the Chinook.

The pilot, Pushp Vaid, continued to express his feelings guilt at escaping where so many others did not when he spoke to the Press & Journal in 2016.

No blame was apportioned to him in the official AAIB report into the crash, but Mr Vaid spoke eloquently of how the tragedy had left him haunted.

He said: “On the way out, we had no problem and on the way back the accident happened, just two minutes before landing basically.

‘There was a huge bang, then we fell’

“Just before there was a whining noise in the cockpit which didn’t sound dangerous. We were not alarmed by it.

“It was just something we had not heard before. It was something myself and my co-pilot were discussing.

“It was the gearbox which was cracking up – and the noise we heard was that – and when the gearbox broke, the rotor blades crashed into each other.

“The back rotor disappeared and parted company from the helicopter and everything just disintegrated after that.

“The accident was instantaneous and, when the rotors hit each other, there was a huge bang and then the helicopter was flying at 100 miles an hour and then it basically, to me, it looked like it was going up but it wasn’t, it was going backwards, towards the sea.

“The cockpit kept on going down and down maybe 30, 40 feet. Then it stopped and the emergency window had fallen off at impact, so the window was open and I swam out.

“It was 11.30 daytime, brilliant sunshine. I could see the sunlight and I found some wreckage (and clung on).”

“I was glad I was alive and just so sad that others didn’t make it.

“I still feel guilty (and think that) maybe I could have done something, but it was mechanical failure, so there was nothing I could have done.

“The gearbox had broken the helicopter and it had broken in mid-air. I pray for the souls of the people who left us.”

The majority of those who perished were from the north-east and their stories were gradually revealed in the days and weeks after the crash.

They included a well-known Aberdeen rugby player, Doug Lowson, 30, who had captained Gordonians the previous season and whose death prompted the club to call off their matches that weekend as a mark of respect.

Others who never came back included Michael Standing, a 37-year-old Telecoms engineer; Aberdeen University graduate Colin Hepburn, 28, who had only recently started work as a planning engineer; Alexander Smith, 57, a chartered mechanical engineer, who had been paying his first visit to an oil platform in about a year; and James Cheyne, 46, a former slaughterman and taxi driver, who had been employed offshore for seven years.

The 45 men who were killed in the worst offshore helicopter accident in Scotland’s history were remembered at a service marking the 30th anniversary of the tragedy at the Kirk of St Nicholas in Aberdeen.

The poignant service in November 2016 included an act of remembrance, where the names of those added to the book of remembrance were read out, followed by a piper’s lament and a minute’s silence.

The Rev Gordon Craig, the chaplain to the oil and gas industry who officiated at the service, said: “It is really important for families to realise their loved ones are still being remembered and respected by the industry.

Their memory will live on

“Thirty years on from the Chinook crash may seem like a long time, but the memories are still vivid for those who lost loved ones suddenly and tragically.

“The pain may be more manageable, but there will still be times when the loss is felt deeply by those who lost loved ones.”

There have been many other fatal helicopter accidents in the North Sea in the intervening three-and-a-half decades.

But none was as grievous as on that beautiful, but grim day in Shetland.