The man tasked with catching one of the most notorious serial killers this country has ever known came from humble origins in Caithness.

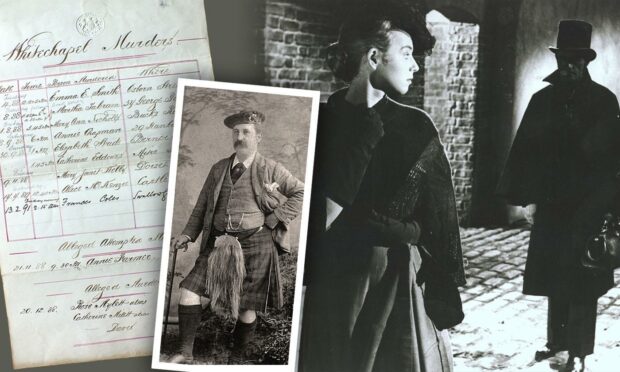

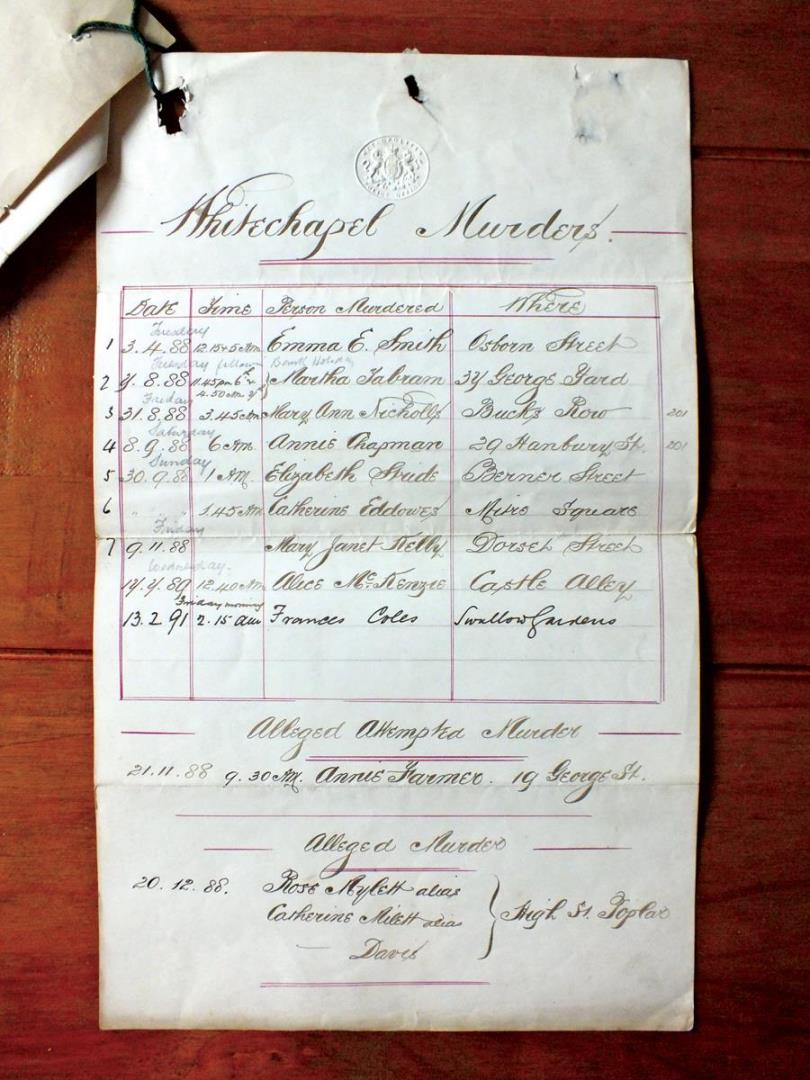

Donald Sutherland Swanson was Jack the Ripper’s nemesis during his reign of terror in London’s seedy underbelly in the late 1880s, when the depraved killer left a trail of possibly 10 mutilated victims, mainly prostitutes.

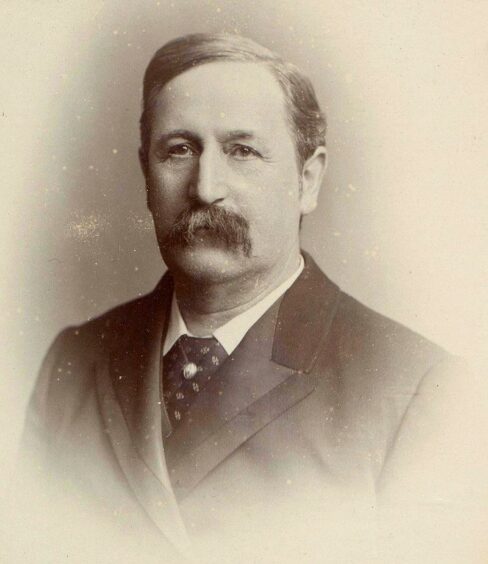

Superintendent Donald Sutherland Swanson from Thurso was pretty sure he knew the Ripper’s identity, and noted it in his famous ‘Swanson Marginalia’- but the suspect was never brought to court due to the fear of a key witness.

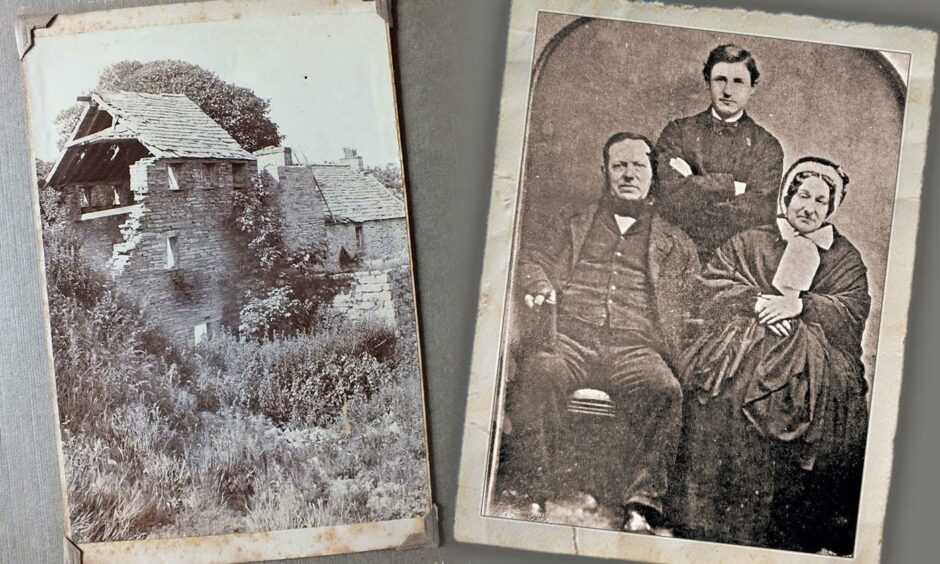

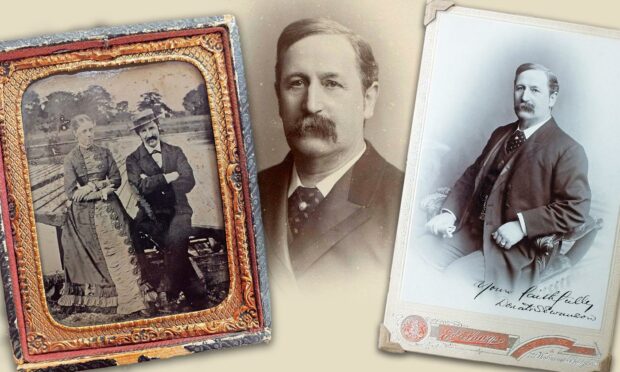

Donald was born in 1848 to John and Mary Swanson in the farmhouse attached to the distillery they ran at Newlands of Geise.

From this tiny hamlet the family moved to 30 Durness Street in Thurso three years later.

Donald’s education began at the Parish School, Market Place, and continued to the Miller Institution in Sinclair Street.

He was something of a star pupil and expected to go into teaching, becoming a pupil-teacher at the Miller.

But Donald decided teaching wasn’t for him, and headed for London where one of his sisters was living.

Although policing was in the family – his older brother John joined the City of London police before going to Edinburgh police force and from there rising to Superintendent of the Aberdeen police – it didn’t appear to be in Donald’s mind at that point.

He took a job as a clerk at the offices of John Meikle in the roaring, stinking morass of Victorian London.

The contrast between the clear air and big skies of Caithness and the literal cesspit of the city at the time must have been a shock to the sensibilities of the young Donald.

But he wasn’t deterred. When John Meikle decided to retire some nine months later, he spotted an ad in the Daily Telegraph and applied to join the Metropolitan Police.

Street bobby

He must have made a good impression, as a few weeks later he was in, trained as a street bobby and sent out to King Street police station in Westminster.

Although he was quickly promoted through the constable ranks, his career wasn’t without blemish at this stage.

Donald rebelled against the rule-bound stuffiness of the Met at this time, and had his knuckles rapped a few times.

He was fined for being in plain clothes without leave; cautioned for receiving a shilling from a prisoner for bail, cautioned for being late on roll call and climbing over the railings to avoid detection.

But his superiors obviously saw something in him, and he continued to climb up through the ranks.

Aged 23, he was police sergeant at Bow Station – with a minor hiccup when he was fined for being outside The Lion public house in Carlton Square with armlet off while on duty – then he became station sergeant at Plaistow station.

Donald turns detective

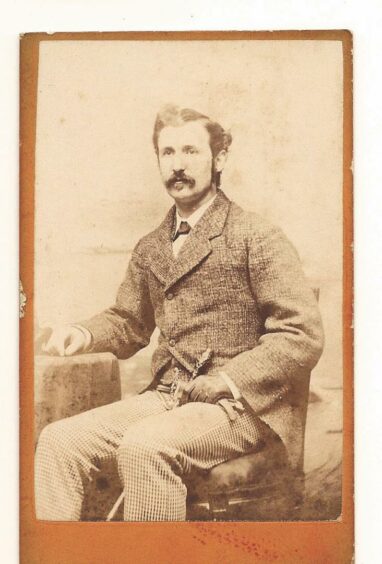

The defining moment in his career came in 1876, when he joined the Detective Department and transferred to Scotland Yard.

Some of his cases sound straight from the pages of Arthur Conan Doyle, involving child kidnapping, bodysnatching, sophisticated frauds by people posing as spiritualists or aristocrats, the theft of a Gainsborough portrait of the Duchess of Devonshire, the case of the Quarter-Million Pound Pearl, the case of the Veiled Lady of Houghton, not to mention a running face-off with the Fenians during their bloody uprisings in the city.

Donald benefited handsomely financially from some of the cases, including the Quarter-Million Pound Pearl robbery, when a grateful Earl of Bective rewarded him with £200 for the recovery of Lady Bective’s jewels.

He cracked a horrific body snatching case – that of the 25th Earl of Crawford – in the ‘Dunecht outrage’ and managed to capture a pseudo-baronet forger who had been conning people in Caithness.

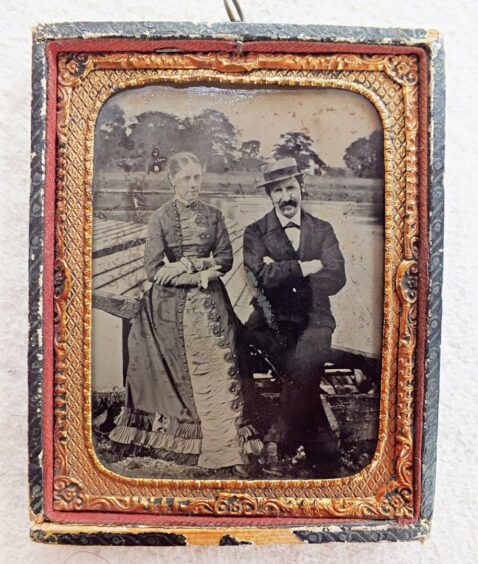

With his career on the up, Donald married Julia Ann Nevill in 1878, and became father to his first son, Donald Nevill, in February 1879.

Now he was a Detective Inspector, and sent abroad in pursuit of dastardly crooks, including to Toronto where he was instrumental in the arrest of notorious bank robber Charles ‘Piano Charley’ Bullard and to New York after a forger.

His biographer, Adam Wood, says his talents were well recognised and he was being groomed for the top job.

“His boss, Detective Chief Constable Frederick ‘Dolly’ Williamson, recognised in Mr Swanson a quite unusual originality of method, and gave him every opportunity of exercising his own special talent.”

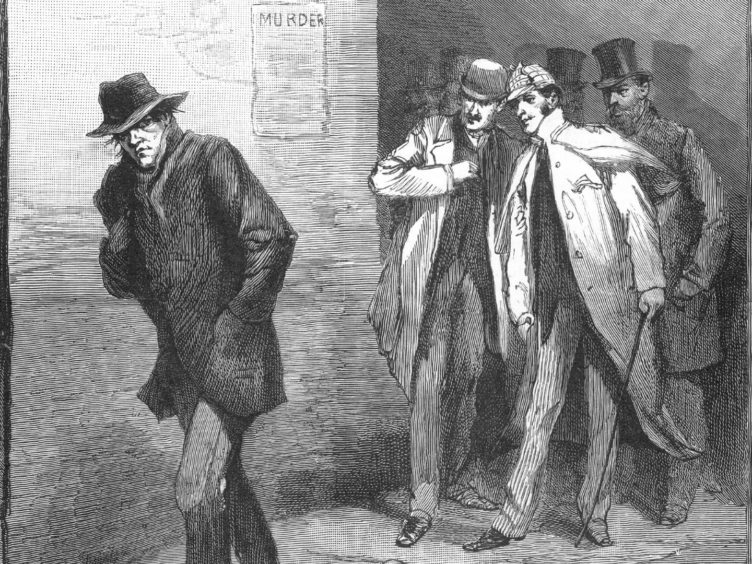

The Ripper’s reign of terror begins

By 1888 Swanson had been 20 years with the Met, and was one of just five Chief Inspectors in CID at Scotland Yard.

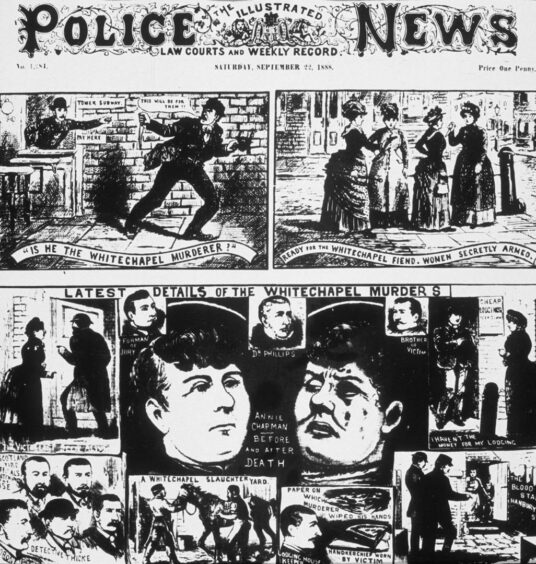

Then came the first Whitechapel murder, marking the start of Jack the Ripper’s reign of terror.

Swanson was assigned to the case, by order of his boss Commissioner Sir Charles Warren.

“I feel therefore the utmost importance to be attached to putting the whole Central Office work in the hands of Chief Inspr. Swanson who must be acquainted with every detail.

“I look upon him for the time being as being as the eyes & ears of the Commissioner in this particular case.

“He must have a room to himself, & every paper, every document, every report every telegram must pass through his hands.

“He must be consulted on every subject. I would not send any directions anywhere on the subject of the murder without consulting him. I give him the whole responsibility.”

Swanson’s burden

The pressure of this responsibility, plus the gruesome nature of the Ripper’s modus operandi, must have placed Swanson and his family under huge strain.

Julia gave birth prematurely to twins on January 2 1889, one of whom died 40 days later.

Adam Wood says little William Alexander Swanson could be seen as an indirect victim of The Ripper.

An insight into the exhaustive police investigation comes from a report by Swanson on October 19, 1888.

“…80,000 pamphlets to occupier were issued and a house to house enquiry made, also Common Lodging Houses were visited & over 2000 lodgers were examined.

“Enquiry was also made as to sailors on board ships in Docks or on the river, about 80 persons have been detained at police stations & their statements taken and verified by police, and enquiry has been made into the movements of a number of persons estimated at upwards of 300, respecting whom communications were received by police & such enquiries are being continued.

“Seventy six Butchers & Slaughterers have been visited & the characters of the men employed enquired into, this embraces all servants who had been employed for the past six months.

“There are 994 Dockets besides police reports.”

Nearly 500 people were being investigated and the subject of written reports, all of them read and processed by Swanson, who therefore knew more about the case than any other police officer.

Swanson’s suspicions

Swanson had strong suspicions about who the Ripper was.

A Polish Jew named Kosminski was under extreme suspicion and surveillance, and Swanson names him in his ‘Marginalia’, but there was not enough evidence to secure a conviction.

The one witness who got a good view of him refused to testify in court, because as Swanson wrote, “the suspect was also a Jew. And because his evidence would convict the suspect, and witness would be the means of murderer being hanged which he did not wish to be left on his mind”.

Scotland Yard had to content themselves with the fact that he was committed to a lunatic asylum, where he died shortly afterwards.

Swanson gave an insight into the stresses of the job in evidence he gave to a the Committee of Enquiry into Police Superannuation in 1889.

“A man may not be, physically or mentally, apparently unfit, but after twenty-five years a man gets so excessively nervous that, if I were to entrust him, as I would have to entrust him, with an important matter, I should feel altogether lost, and prefer to do the thing myself, and therefore I feel sure that, by the time a man had served twenty-five years, he would be so exhausted that he would not be worth his money.”

We learn much about Swanson from contemporary crime journalist Charles Windust, who wrote: “Mr. Swanson is a handsome man of sturdy build, with a quick wit, and a resourceful mind – a thorough man of the world – though not all the criminal experiences of many years have succeeded in altering an iota his kindly disposition.”