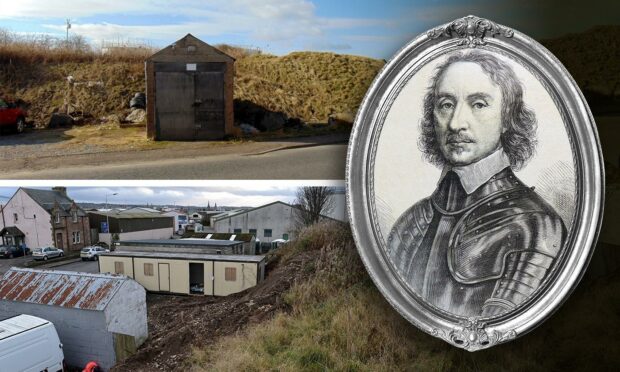

It may just look like a large mound of earth by the river’s edge in Inverness, but it’s a large mound of earth of national importance.

The massive overgrown heap by Lotland Road in Inverness holds centuries of history as the last remaining evidence of Oliver Cromwell’s ‘citadel’, built in 1652 to house a garrison of men ready to subdue uprisings by the Royalist armies of the Highlands.

Recently a section of it was gouged out by a local business unaware of its significance, prompting a temporary stop notice by Historic Environment Scotland (HES).

HES staff have visited the monument as part of their investigations into the incident.

A spokeswoman from the organisation said: “The earthen bastion and ramparts next to Lotland Road in Inverness are all that remain of a once-large and imposing fort positioned on the banks of the River Ness.

“The fort was one of five massive citadels constructed by Oliver Cromwell during the English Commonwealth’s occupation of Scotland in the 1650s.

“It was constructed from masonry taken from Greyfriars Church and St Mary’s Chapel in Inverness, and the monasteries of Beauly and Kinross, as well as the episcopal castle of Chanonry, all of which Cromwell demolished for that purpose.

“In recognition of its national importance to Scotland’s heritage, the remains of the fort are protected as a scheduled monument under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979.”

The gouging of the rampart is just the latest in a series of incursions into the huge bank over the years by local businesses trying to eke out more space away from the busy road mere feet away.

Local history enthusiasts George Glaister, Dave Conner and Adrian Harvey of Inverness Local History Forum (ILHF) went to have a look at the damage.

Adrian described the damage as ‘dispiriting’ while George said until fairly recently there used to be three such ramparts still in existence.

“They were very similar to the ones in Fort George, and over the years they’ve been cannibalised and only this one remains.

“If it was strimmed and landscaped with an information panel it might have prevented this from happening.”

Adrian added: “People need to know it’s not just a slag heap or an industrial mound but of historical significance.”

Dave Conner said many in Inverness were unaware of the Cromwell’s citadel, even though there was a Citadel football club and a Citadel bar at one time in the area.

“Over the years the site has been eroded for all sorts of purposes, but this part has been left for a long time, so it’s a shame to see this damage.

“It’s part of the history of Inverness, and a shame we’re not marking that by showing folk what the history is.”

HES said Cromwell’s Citadel is in private ownership and although a scheduled monument, doesn’t require the owners to maintain it, provide interpretation or open up access.

“However, such an important monument would benefit from greater recognition and we regularly provide advice to owners about promoting positive management of scheduled monuments.

“HES would support any potential proposals for signage highlighting the monument’s significance.”

Attacks from the sea

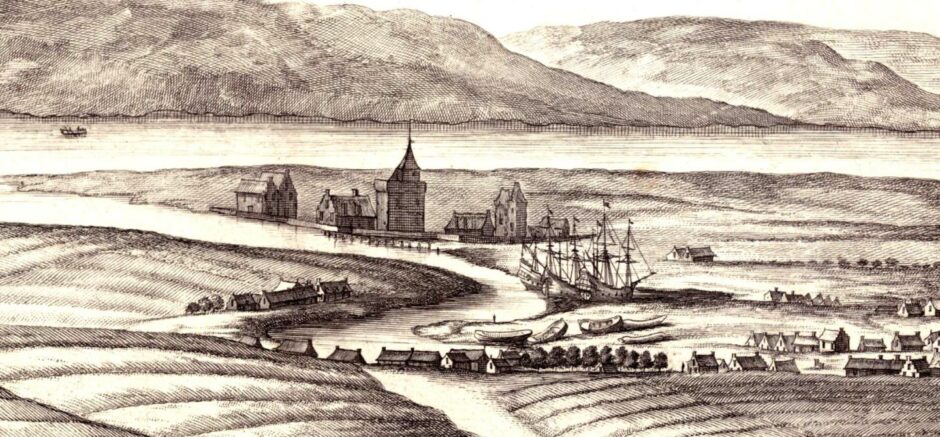

Cromwell was strategic in his placing of the fortress, knowing Royalist attacks would come from the sea.

The structure was five-sided, built back from the river bank and with access for ships at high tide.

It was a mammoth construction.

The walls were three storeys high, built of hewn stone lined with a brick wall, with watch houses on each of the five corners.

On the town side was a ‘sally-port’ or controlled entrance, and on the north side was the main gate with an oak drawbridge, known as the blue bridge.

‘A most stately sconce’

In his Wardlaw manuscript of 1674, James Fraser details how Cromwell’s government bought the land, called Carse Land, from the Burghers of Inverness for the fort, ‘a most stately sconce’.

“The entry from the bridge into the Citadel was a stately vault about 70ft long with seats on each side and a row of iron hooks for picks and drums to hang on.

“In the centre of the Citadel stood a great four square building of hewn stone called the magazine and granary; in the third storey was the church, well furnished with a stately pulpit and seats; a wide bartizan (overhanging corner turret) at the top and a brave great clock with four large gilded dials and a curious bell.”

The fort cost a pretty penny – £80,000 – and with wages at a shilling a day, many willing country folk turned up for the work.

But the massive structure wasn’t in use for long.

The garrison was withdrawn by popular demand after the 1660 Restoration, the buildings pulled down and the site abandoned.

Stone was taken from the site in the 1680s to build the old seven-arch Ness Bridge, washed away in 1849, and also for a previous version of Inverness Castle.

You might also enjoy:

Cromwell and the dangerous streets of Inverness