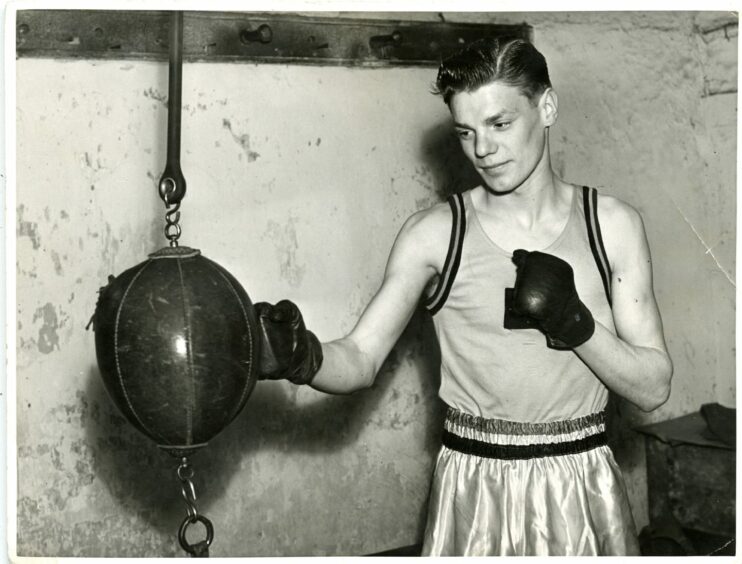

He was nicknamed “Dandy Dick” by the esteemed boxing commentator Harry Carpenter.

And, although it’s a lottle matter of 66 years since a tough-as-teak, but smart-as-paint Dundonian surged to golden glory with a series of memorable performances in the lightweight division at the Melbourne Olympic Games in 1956, there’s still something of the blithe boy about Dick McTaggart.

For many, this character is his city’s greatest-ever sportsman and there are distinct similarities between him and Aberdeen-born Denis Law.

Both emerged from working-class backgrounds and have laboured tirelessly at the grassroots to encourage youngsters to kick a ball or hit a punchbag.

Both have had statues sculpted in their honour, yet remain as down-to-earth and approachable as they were at the height of their powers many moons ago.

And though neither lives in the city with which they are most frequently linked – Denis stays in Manchester and Dick is based in Troon – there won’t be many people in the north-east of Scotland whose eyes don’t twinkle when they reflect on the achievements of these two extraordinary individuals.

The long and winding road to Oz

It was another time, another place when the 21-year-old boxer travelled to Melbourne on his maiden Olympic mission in November 1956.

And it’s little wonder that he was glad to arrive in Australia after a gruelling journey which took five days and included a stop-off in Honolulu which was a place of exotic beauty for the boy from a Dens Road tenement building.

This was long before there was Lottery funding or any semblance of Team GB, but Dick – a gifted pugilist with a style and technique which impressed the cognoscenti – had no intention of simply making up the numbers.

On the contrary, as somebody who had grown up in a family with a flair for the fistic arts, the Scot was desperate to prove his mettle to the world.

He recalled: “People had told us before we left that we should go there and enjoy ourselves, with the Olympic motto being all about taking part.

“But I wasn’t interested in going all that way just to enjoy myself. I wanted to get a medal. I didn’t care what colour it was, as long as I got a medal.”

Soon enough, he was on the charge, bewitching, bewildering and beating opponents and although he was the underdog when he met Harry Kurschat, the reigning European champion from Germany, in the final, Dick ducked and dived and displayed derring-do and lashings of skill to gain the victory.

Another prize was soon awarded

He said later: “I hadn’t known any of the other lads I had fought, but everybody had heard of Kurschat and he was good.

“But I had him down twice in the first round and thought it was all over. However, credit to him, he got up twice and came back strong. But I won it clearly enough in the end and it was just such a fantastic feeling.

“I had collected my gold medal and wanted to go away and celebrate with Terry Spinks, who had also won gold, but I was told by the officials: ‘Do not leave the hall, there might be a wee surprise for you’.

“Then, later on, they announced that I had won the Val Barker Trophy [which was awarded to the most stylish performer in all the weight divisions at the Olympics] and that meant more to the British delegation that any of the other medals and prizes, because no British competitor had ever won it before.

“And I reckon that I must have filled the trophy up with champagne about 150 times that night as everybody celebrated.”

Dick’s exploits gained him instant fame and there were plenty of offers to turn professional, but this shrewd individual has always worked on the basis that he would forge his own career path and trust his instincts.

Besides, he was thrilled when he eventually returned home and discovered that his mum and dad were waiting for him in London and the pride in their eyes at his achievements meant more than any pound signs.

He told The Courier: “They had never been on a plane before, but they had flown down to meet me specially.

“Then, when we got the train back to Dundee, thousands of people in the city turned out on the streets to welcome me home. It brought tears to my eyes.

The party brought Dundee together

“Fellow boxers John McVicar and Peter Cain hoisted me up on their shoulders and carried me up the stairs out of the railway station.

“And then, there were thousands of people who had lined the streets and were cheering. I couldn’t believe this was happening.

“We got in an open top motor and made the journey up to our house at Dens Road. It was unbelievable, but it was the greatest thing in the world.”

It was just a few weeks before Christmas – these Olympics had started in November and he won his gold medal on December 1 – when Dick was acclaimed as the toast of his community and his name became a byword for boxing excellence the length and breadth of Britain, even as he was presented with a Rolex watch by the city fathers in Dundee.

But he wasn’t finished with the Games. Or in meeting legends on his idiosyncratic path to sporting greatness.

Muhammad Ali was the best of all

When Dick ventured to Rome for the 1960 Olympics, plenty of pundits predicted he would defend the title he had secured four years previously.

But these global Games regularly throw up some controversial outcomes, particularly when there are judges involved and he had to be content with a bronze in the Italian capital after losing in the semi-finals to the eventual champion Kazimierz Pazdzior of Poland.

He was pretty stoical. “I felt I won the fight and it was really disappointing. But looking back now, to get a medal of any sort wasn’t bad.”

And it offered him an opportunity to meet and break bread with a young man called Cassius Clay, who was poised to become a superstar in the next decade.

Dick’s reputation as the best amateur on the planet – he was so described by the aforementioned Carpenter – carried a lot of weight in the sport.

So he was welcomed into the US team canteen and gained the chance to find out if the hype about Clay was justified. Yes, it was.

As he said: “The Americans invited me to eat with them in their canteen. I was introduced to Cassius, whom everybody had been talking about, and even then, he was shooting his mouth off and telling everybody he was going to be the heavyweight champion of the world.

“He was great fun to be around, though, he had so much talent and charisma and I thought he should have got the Val Barker trophy at those games.

“He was also a gentleman and, when I watched him fight, it was obvious that he had the ability to back up all the things he was saying.”

When Muhammad Ali finally died in 2016 after suffering from Parkinson’s disease for many years, it was a reminder of the inherent dangers for any boxer who takes sustained blows to the head.

Dick had noticed he was increasingly feeling the pain by the mid-1960s, not long after his third and least successful appearance at the Olympics [in Tokyo]. So he wisely stepped away and transformed himself into a coach, a mentor, a motivator and inspiration for so many youngsters in his homeland.

But he was as star-struck by Ali as anybody else. And, after the American’s death, Dick said: “He was a class apart. You could see it. He was so special!”

Money never came into it

All those years later, the wiry Scot who won 610 of his 634 amateur bouts remains the only man from his country to strike gold in Olympic boxing.

He was thrilled at the reception and has derived a huge amount of satisfaction from the creation of such enduring legacies as the Dick McTaggart Centre in, where else, his beloved Dundee.

There are no regrets about remaining an amateur, even though he was offered £1,000 by one promoter in the 1950s which “was a fortune in these days”.

He said: “I enjoyed boxing, but I never wanted it to become my job. I knew that I didn’t have many brains, but I wanted to keep the ones that I had.”

At 86, it sounds like he made a smart move – as always!

More like this:

Reliving the glory days of Dundee’s Dick McTaggart Centre

How Smokin’ Joe Frazier ended Muhammad Ali’s unbeaten record 50 years ago

Stuart Cosgrove: How Cassius X became Muhammad Ali in the summer of 1963