In 1940, three German spies were dumped in the Moray Firth tasked with making their way to London – but they were no match for Buckie’s bobbies.

The hapless trio – spiv businessman Karl Drucke, weedy Werner Walti and enigmatic beauty Vera Eriksen – were invasion spies.

They were tasked with travelling to London carrying vital equipment ahead of a perceived German invasion on British shores.

But their plan was rumbled by suspicious locals and they found themselves on death row.

Condemned men

On a warm day in early August 1941, two condemned men sat in adjacent cells in Wandsworth Prison, London.

Drucke and Walti were to be hanged the next morning.

Famous hangman Albert Pierrepoint had already sized them up; their weight and build would decide ‘the drop’.

They would be executed together, convicted by separate juries of being German spies for their actions in 1940.

Section one of the Treachery Act 1940 made it clear: any attempts to assist the enemy or impede His Majesty’s Forces would be punishable by death.

The pair had been caught in possession of weapons and wireless equipment.

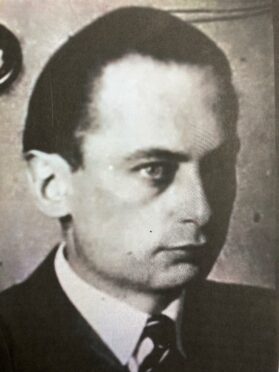

An odd pair, Drucke was 35, claimed to be Belgian but had been educated in Germany and spoke French.

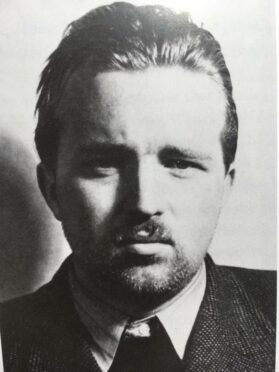

Slow-witted Walti was in his 20s, claimed to be Swiss but spent most of his life in Germany.

They hardly knew each other but were low-level intelligence gatherers, part of a vast web of spies and chancers that operated across German-occupied territory.

They had given little away during interrogation because they had nothing of value to give.

It must have dawned on them that they had been sacrificed – betrayed by their masters and they must have wondered what happened to their team leader, Vera Eriksen.

Femme fatale

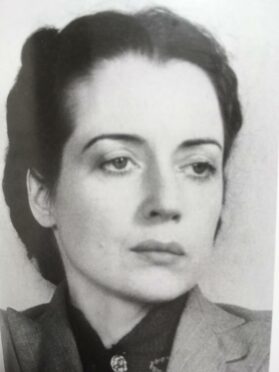

Where was Eriksen, Drucke’s lover, the enigmatic beauty with all the connections?

Following their arrest, she had simply disappeared.

If Drucke and Walti were hapless, their missing leader was anything but.

Alluring beauty Eriksen, a 28-year-old Dane born in Russia where her father was a diplomat, was trained as a ballet dancer at the Bolshoi.

Her dancer’s poise added lustre to her beauty. She lived in London before the war, where she had mixed with the remnants of the old European aristocracy.

Eriksen was also a spy, supporting her lifestyle by passing snippets of gossip to German and British Intelligence – MI5.

While the Germans knew nothing of her MI5 contacts, the British were well aware of her German connections.

Many ‘casual’ intelligence officers operated in London and as war approached, most fled, Eriksen among them. Those foolish enough to stay were quickly interned on the outbreak of war.

This was catastrophic for German military intelligence, the Abwehr.

Back in Germany, Eriksen’s tangled love life took a turn when she fell in with a senior German intelligence officer, Captain Hans Dierks.

It was a fateful union at the beginning of a remarkable chapter in the history of the secret intelligence battle that was fought in the shadows during the length of the war.

Plan hatched for invasion spies

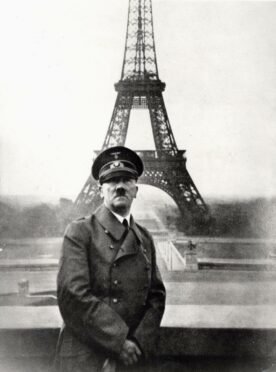

It began with unexpected success. Hitler’s plan for Europe estimated that it would take all of 1940 to subdue France, with the invasion of Britain to follow in 1941.

But the battle of France went better than planned and by June 1940 the invasion of Britain (Operation Sea Lion) was brought forward.

Chief of German intelligence, Admiral Canaris, was instructed to prioritise Britain, but the Abwehr were badly placed; they had lost most of their agents.

The scene was set for one of the most bizarre chapters in the history of espionage.

Putting deep cover agents in enemy territory is a complex business, but there was no time. Something quicker was required so the plan for ‘invasion spies’ was hatched.

It was a cheap and cheerful solution. The Abwehr would flood Britain with dozens of basically-trained spies tasked with simple sabotage and intelligence gathering.

Most would not survive for long, but that didn’t matter. Anyway, since the invasion of Britain was imminent, agents would only need to survive a few weeks.

But behind the bravado it was such an obvious ‘one-way ticket’ that few selected as invasion spies were actually German.

Why sacrifice good Germans when there were so many expendables in the French and Dutch prisons under control of the Gestapo?

The prisons of occupied countries were ‘combed out’. Some inmates were executed, others were given an ultimatum – spy or die.

Spy or die

Most invasion spies were not volunteers, but were forced by fear or obligation.

Drucke and Walti were both recruited from prisons. The prospect of freedom was worth the risk – surely anything was better than a Nazi prison?

Neither spoke fluent English but that didn’t matter. They were transported to Hamburg, the co-ordinating centre for invasion spies, and given basic training.

There they were joined by Eriksen and Captain Dierks.

Eriksen and Drucke knew each other from pre-war Paris. They had been lovers and their passion was rekindled.

Captain Dierks found himself in a quandary; he was part of a love triangle with two of the three agents he was compelled to send to Britain.

They were a motley crew but the pressure was on.

Eyes and ears were needed on the ground; the three agents would be landed in Britain as soon as possible.

Captain Dierks could not take part himself; he knew too much to risk capture. Eriksen, Drucke and Walti would undertake the mission.

Norway to the north-east

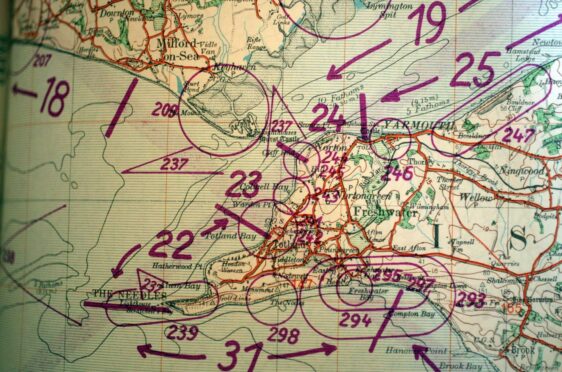

Because of the high invasion alert in the south of England, it was decided to land the group in north-east Scotland.

The route hadn’t been used before, but there were German bases in Norway a short trip across the North Sea.

The training for invasion spies was inadequate, as was their equipment.

Poorly forged identity papers and badly counterfeited English bank notes were issued.

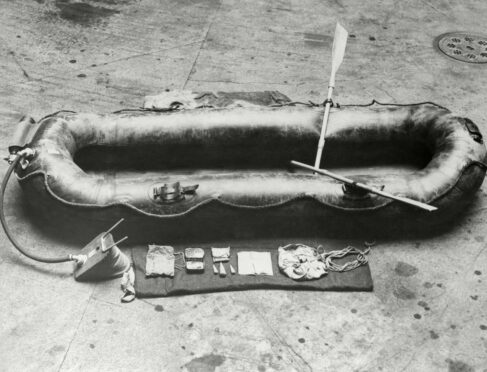

The two men were given a small automatic pistol, a knife and a radio along with code discs – all of obvious German manufacture.

The plan was simple. On landing, the group would split up.

Eriksen and Drucke were to travel to London where she had contacts.

Walti was to make his way south alone, observing aerodromes and harbours en route, reporting back by radio.

The method of transport for their secret mission was to be three English bicycles, looted from the British embassy in Oslo.

The prospect of peddling 600 miles to London, in possession of German spying equipment, must have struck the naïve agents as nothing short of a suicide mission.

Little wonder that the group decided on a night out in Hamburg before leaving for Norway.

Futile mission

Perhaps drowning their sorrows, the three agents and Dierks enjoyed a night of heavy drinking before he drove them back to their quarters.

It was then that things started to go badly wrong. Dierks crashed the car, killing himself and injuring the others.

With the chief planner dead and the others injured, the operation should have been cancelled – but no.

Battered, bruised and with Eriksen as unofficial leader, the three were bundled aboard a boat to Norway the next day.

They were a sullen and dispirited group; Eriksen was terribly conflicted by Dierks’ death. She also believed she was pregnant by him – or perhaps by Drucke.

For Drucke and Walti, a Nazi prison may have seemed an appealing prospect after all.

Unbeknown to all involved, their mission was unnecessary.

Operation Sea Lion had been postponed, the Battle of Britain had been lost.

There would be no invasion of Britain in 1940 – but no one thought to inform Hamburg.

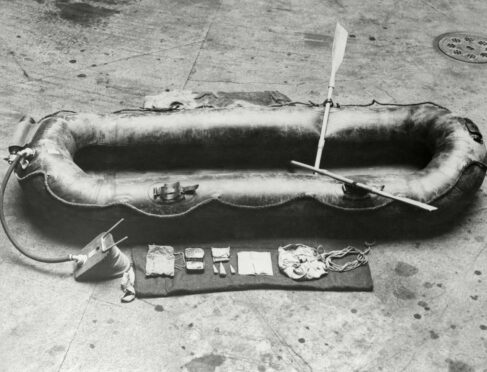

It was all too late. In the early hours of September 30 1940, a Heinkel seaplane landed in rough seas a mile offshore in the Moray Firth.

Suspicious characters

The tide was against them and it took four hours of hard paddling to reach the shore.

It immediately became apparent that their 10ft rubber dinghy could not be paddled with three bikes aboard.

The bikes were ditched into the sea and the mission was unravelling before it had begun.

At 8am the exhausted and bedraggled agents stumbled up the beach near Buckie.

They immediately split up – they would travel by train.

Walti headed for Buckpool Station and the line to Edinburgh; Eriksen and Drucke to Portgordon and the London train.

Walti soon caught his train, but sitting in the quiet waiting room at Portgordon Station, Eriksen and Drucke soon began to arouse suspicion.

They believed they would blend in with the crowd of Poles exiled in Scotland.

There were large numbers of Polish soldiers and refugees, but none near the quiet fishing towns of Moray.

The pair stuck out like sore thumbs and the station master’s suspicions were further aroused when Drucke took a large knife from his pocket and cut off a piece of German sausage.

Cover blown

The sausage was proof positive, local constable Robert Grieve was summoned, and he detained the pair and asked to examine their documents.

The sharp-eyed policeman, who hailed from Oldmeldrum, noticed both identity cards lacked immigration entry stamps and the handwriting was in ‘continental style’.

Their mission failed after less than an hour ashore. The pair were arrested and taken to Portgordon police station.

Eriksen carried no luggage but had six passports, all in her name, and a large amount of money.

When Drucke’s luggage was searched, his radio and code cards, pistol, ammunition, knife and the remnants of sausage were found.

His decision to leave his gun in his case demonstrated his lack of training.

Shortly after the arrests, the deflated rubber dinghy was found near the beach and it was reported that a third foreign-looking man had earlier caught a train to Edinburgh.

Edinburgh City Police were contacted and the Detective Superintendent Willie Merrilees took charge.

Inept enterprise revealed

Checking the left luggage at Waverley Station, Merilees found Walti’s case of equipment.

Disguised as a station porter Merrilees and several burly colleagues lay in wait. The hapless Walti was arrested as he returned for his case.

The mission was blown, within hours the three bungling spies were in the hands of MI5.

The two men told identical tales – that they were refugees forced into delivering radio equipment to unknown contacts in London.

Eriksen said little but admitted to being an agent and asked to speak to her contact in MI5, who she knew by a code name.

At first MI5 couldn’t believe the three agents had been sent on such an inept enterprise.

In the words of one senior MI5 officer, they were “thrown into battle in numbers, in the hope that some would get through”.

Drucke and Walti had nothing to offer as double agents.

An example had to be set – there would be no mercy.

Eriksen had been careful not to be in possession of incriminating evidence, but Drucke and Walti had been caught red-handed.

Went to deaths quietly

On July 13 1941 they were tried, convicted and sentenced to death at the Old Bailey, their appeal dismissed on July 21.

During the trial no mention was made of Eriksen other than to say she would not be present in court.

At 8am on August 6 1941, Drucke and Walti were hanged. They went to their deaths quietly, perhaps still believing that they would be reprieved at the last minute.

But in their hearts they must have suspected betrayal.

Ironically, just five years later at Nuremberg, Pierrepoint would hang many of the Nazi leaders who were ultimately responsible for the doomed mission.

Drucke said he and Walti, like most other invasion spies, were like “a beast being taken to the slaughter”.

No happy ending

As for Eriksen, many myths grew around her. Rumours spread that she was living in luxury on the Isle of Wight or London’s West End.

The truth was less glamorous. With her cover blown, she was no use as a double agent.

She was sent to an internment camp for foreign nationals on the Isle of Man to spy on fellow detainees.

A complex character making full use of her charms, she had successfully played a game of duplicity all her adult life.

She was clever, manipulative and exploited by powerful men, in turn exploiting them.

But she was no master spy; she gained little from espionage. Like her tragic companions, she did what she had to do to survive in turbulent times.

And there was no happy ending.

After the war, being of no further use to MI5, she was deported back to Germany.

She never recovered from her time in the internment camps where she contracted tuberculosis, and was dead by the end of 1946.

We have been brought up on the legend of German superiority, but in the secret intelligence war, Britain was always a step ahead – their victory overwhelming.

The tragic comedy of errors that was the case of the three German spies in Scotland was but one bizarre episode in that secret battle.

Tom Wood is a writer and former Deputy Chief Constable of Lothian and Borders Police. He is a member of The Edinburgh, Lothian and Borders Police Historical Society. Story originally featured in 1919magazine.co.uk

If you enjoyed this, you might like: