He survived 40 perilous bombing raids and had five left to do until he completed his tour of duty.

But on the night of October 23 1944, something strange happened aboard William Shepherd’s Lancaster as they flew over Germany.

Bill’s bravery during the incident would earn him a George Medal but it abruptly ended his career as an air gunner in the Second World War.

Bill, of Bridge of Don, was disappointed at that.

He was determined to finish what he had volunteered to do, 45 missions, even at a time when life expectancy for bomber air crew was a matter of days.

The strange incident turned out to be sabotage.

Bill said: “At the time I felt it was a disgrace; I would rather have gone down in flames but I had no choice.”

By then Bill was 21, but he was 16 when the war broke out, and he was determined to join up.

He’d left school at 15, and took odd jobs until he became old enough to join the RAF at 17 years and six months old.

Six months later he was in the thick of it, at a time when Hitler seemed ready to invade British shores any day.

Bill had passed gruelling medicals and physicals, but the air force at that point had enough pilots, navigators and bomb aimers, so Bill became an air gunner.

Night after night he squatted in the mid upper turret of a Lancaster flying out over Europe on deadly bombing raids, his job to shoot down any enemy aircraft coming to take their plane out.

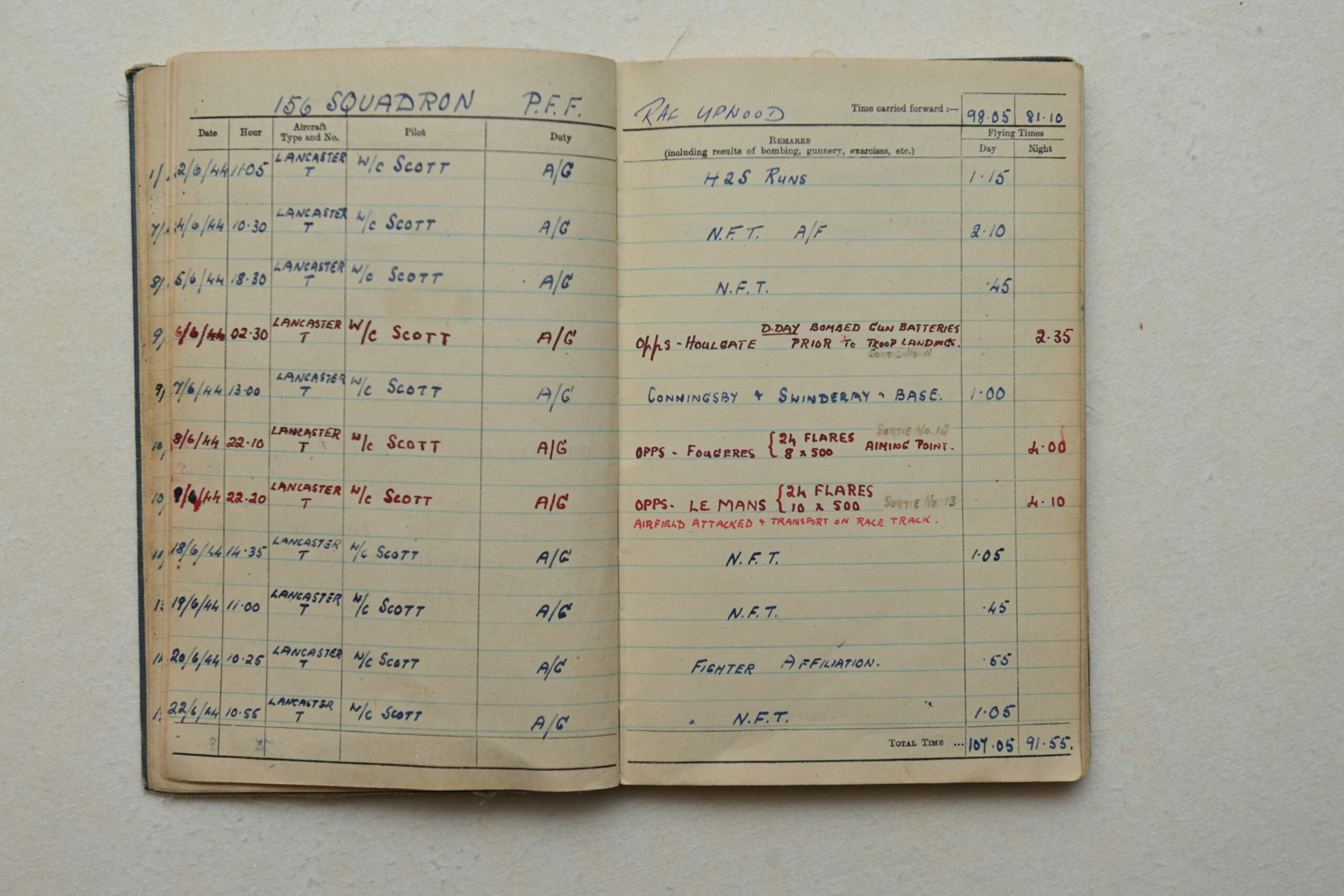

He joined the elite 156 Squadron The Pathfinders force, the RAF’s best crews who flew ahead of the main bombers.

It was their job to brave tracer bullets, flak and enemy fighter planes to guide the bombers to their target, lighting it with flares.

Gunners had nothing but rifles to defend their aircraft, albeit it rifles with superior firepower.

Bill, now 98, lives in a rest home in Forres.

His memories of his war years are crystal clear, and he has many tales to tell.

On D-Day – June 6 1944 – 156 Squadron was on a mission to bomb the array of big guns at Houlgate on the French coast.

Bill said: “They were about five or six miles inland, and in front of them was the Wehrmacht (the armed forces of the Third Reich), they were all lined up there with machine guns so we took out 10 of the biggest guns.

“We knew where they were, as the Maquis (French Resistance) had told us, and we also knew there were women and children there but the Maquis took them to safety.”

Bill had a bird’s-eye view of the biggest seaborne invasion in history.

“It was a lovely sight to see going in in the moonlight, it was about half a moon; looking down, I could see all the bow waves, the Channel from one side to the other was full of boats and ships.

“It was really amazing.”

Another incident saw Bill’s plane on fire after being strafed by bullets and flak.

With the luck that seemed to be on Bill’s side through the war, the Lancaster made it home, but the danger didn’t stop there.

The two massive, 1,000lb American bombs on board had to be taken out once they landed, and five or six armourers flocked round to unload the deadly cargo, bombs now grooved from close encounters with bullets.

Bill decided to head for the crew bus and go and clean his guns when he heard a monumental explosion.

The bombs had gone off, pulverising the air crew, damaging many other planes and taking the leg off Bill’s fellow crewmate, Norman Piercy.

Norman survived and the two remained pals for years afterwards.

On the night of October 23 1944 Bill was on his 40th mission, and not flying with his regular aircraft or crew.

He had volunteered to take the place of another gunner, who was off sick.

The squadron was heading towards Essen, to take out the Krupps arms factory.

The visibility was poor, but they had learned that the weather would clear just before the target.

Bill said: “It did clear and I could see the flames coming from Essen, way in the distance where we were heading.

I could see his fuselage all red, a reflection of the fire at the Krupps works 30,000ft below.”

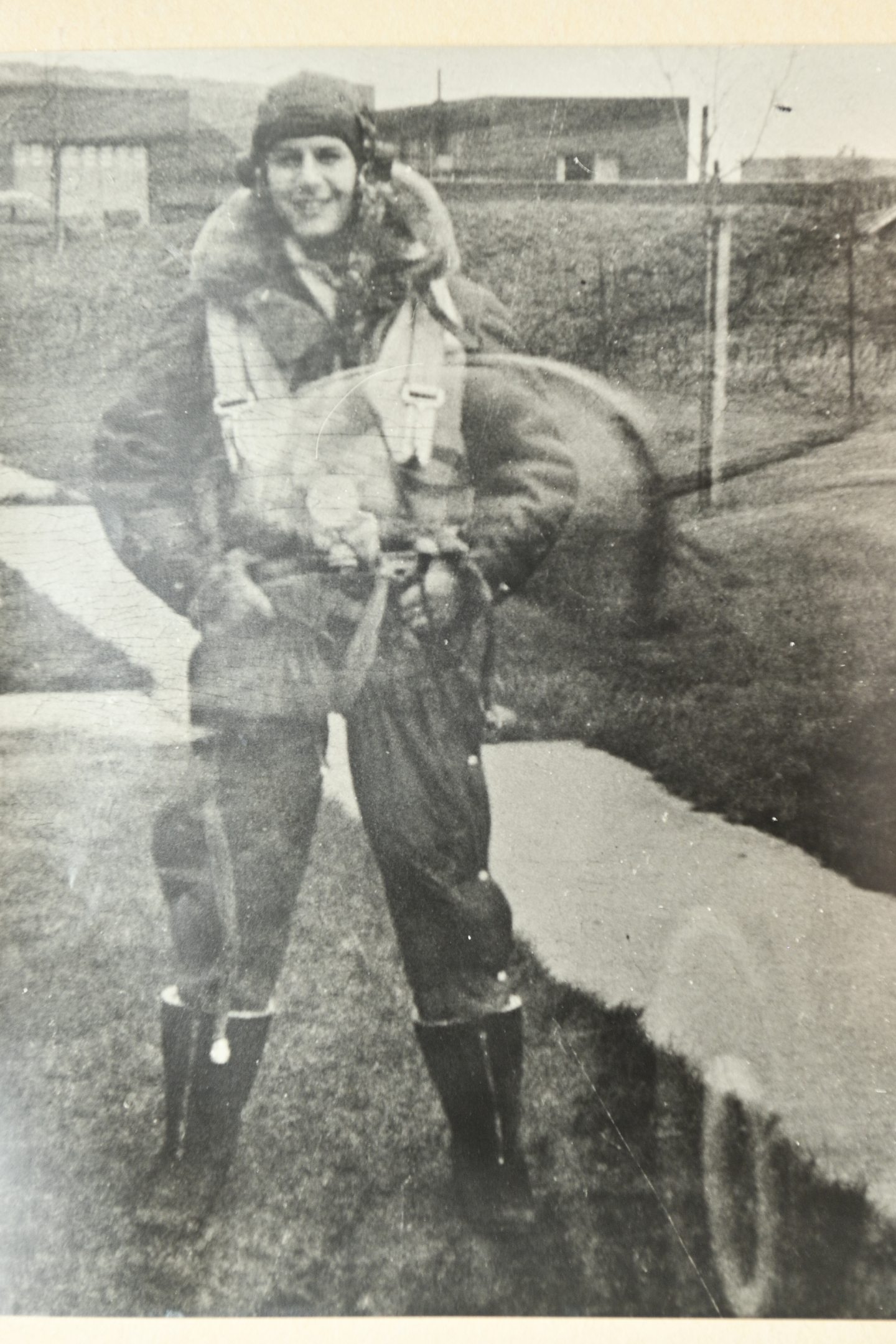

Bill Shepherd.

“I thought it was funny that the crew had gone quiet, no-one answered when I called them up.

“I called the pilot, no answer. I kept trying, nothing.

“It turned out they were all asleep from lack of oxygen, and we’d been completely out of control for 20 to 25 minutes.

“Eventually I roused the pilot and told him to turn the oxygen as high as he could, but he was just mumbling.

“Then I said ‘look at 10 o clock; you’ll see two bombers going a different course from us’.

“That woke him up. We were going back instead of forward.

“A German fighter was watching us, but for some reason didn’t attack.

“I could see his fuselage all red, a reflection of the fire at the Krupps works 30,000ft below.”

The crew ditched their bombs and headed for home.

The next day Bill was sent home for 14 days on survivor’s leave and when he returned, to his disgust, he was told he was to become an instructor, no more missions.

Piecing together the events afterwards, Bill realised the lack of oxygen must have been due to sabotage.

“Two ground crew lads said something was queer about a labourer hanging around the planes, but didn’t report it to our wing commander because he was a bit distant and always busy.”

Bill was awarded the George Medal for his bravery that night but it didn’t arrive until two years later, after Bill wrote off for it.

He said: “I was being treated for TB at the time. A tiny box arrived with the medal in it, wrapped in a crumpled letter from the Air Ministry. There was no band or ribbon.

“I wondered it it had gone to the wrong person.

“Anyway, I was disgusted and chucked it into the back of the wardrobe.”

Meanwhile, Bill entered the grain trade, needing an outdoor life to be able to cope with his tuberculosis.

“By 1959 I was north-east store manager in Inverness. I did well, they were good times.”

Meanwhile, he gave his George Medal to his son in Australia, who tragically died two years ago.

The medal went to his grandson, who, not understanding its true meaning, sold it.

Bill said: “It didn’t bother me. It was the blokes who didn’t come back who should have got the medals.”

What got Bill through the dangers he and countless other airmen faced night after night during those years?

Bill said: “In 1941 it was a hell of a mess. Any day now the Germans would be ashore, that’s what was in our minds.”

He has written some reminiscences in the back of his log book.

“Once our wheels left the runway we were on our own. We had our orders and target, seven of us, bonded together on a gun and bomb platform with four engines.

“All the top brass could do was sit and wait for us to make a success or failure of the mission.

“This was the only time of my life that I would feel complete indifference.

“There was no past, no future.

“My existence was only from one heartbeat to the next.

“When it was all over life would never be the same again.

“Only those who participated in the great air battles over the Third Reich could understand what it was all about.

“Even if you escaped the great reaper, you would spend the rest of your life wondering, why?”

You might enjoy: