He was an actor who never signed autographs, refused to indulge in press interviews, loathed all gossip, turned down a knighthood and objected so much to his voice being used in advertisements that he once sued Heinz in a notorious court case.

That brief resume might indicate that Alastair Sim was the ideal fellow to play the title character (Ebenezer) Scrooge in the classic 1951 film version of the Charles Dickens novel A Christmas Carol; his performance serving as the benchmark against which all others are set.

But Sim, who was born to Isabella, a Gaelic speaker from the Isle of Eigg, and Alexander, a successful tailor in Edinburgh in 1900, was a mass of contradictions during his career on the stage and the silver screen.

After starting a degree course in analytical chemistry, he suddenly told his parents he intended to become an actor and the announcement was so badly received that he left home under a cloud and spent a year “off grid” in the Scottish Highlands with a group of itinerant jobbing workers.

It was the sort of spur-of-the-moment decision that could have ended in calamity but, instead, he went on to become one of the greatest and best-loved performers of his generation in a string of hit films, including The Happiest Days Of Your Life, Laughter In Paradise, The Belles Of St Trinian’s and An Inspector Calls.

And, of course, he also brought the world’s most famous miser to life.

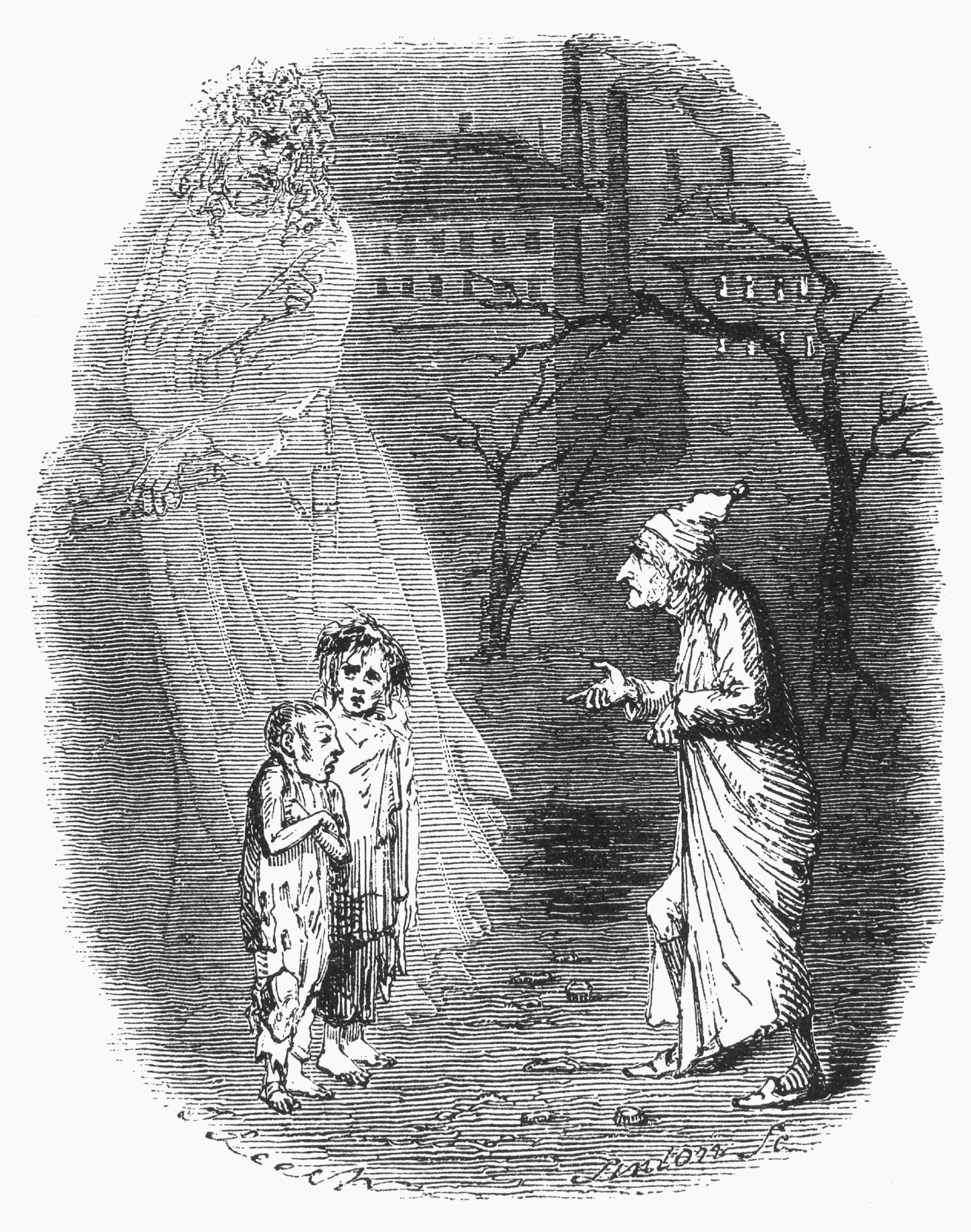

The Scot’s portrayal of Scrooge managed to convey both the miserable, morose tightwad who is famously prone to uttering “Bah Humbug” in the early part of the proceedings and his transformation into an affable eccentric who recognises what an old fool he has been in the closing pages.

Sim, who had previously rejected a part in Whisky Galore, because he had no interest in becoming “a professional Scotsman”, brought comedy, terror, sadness, pathos and quirkiness to the movie as nobody had done before.

Stephen Fry is among those who was enchanted by his performance and said in matter-of-fact fashion: “He is the perfect Dickensian character.”

The film struck a chord with audiences across the world and, 70 years later, it has lost none of its magic spell and haunting qualities.

The New York Times responded: “Tall, bald and pouch‐eyed, with a velvet voice, a droll wit and the face of a cunning bloodhound, Alastair Sim was one of the masters of British stage and screen comedy, a performer who made audiences twitter and roar with subtle ease.

“His (Scrooge) exposes much more than the grief and despair of a nasty old man. He exposes a sort of wretchedness of the soul – a hollow‐eyed horror of the void that is not only before him, but on all sides because of his longtime indifference to affectionate association with other men and women.”

Edinburgh’s link to Sim and Scrooge

Away from the camera, though, Sim was an avuncular individual who loved helping others – and particularly youngsters in search of guidance.

He and his wife Naomi Plaskitt – they met when he was 26 and she was 12 and were married for 44 years until his death in 1976 – actively promoted and encouraged young acting talent for several decades.

Among their proteges was George Cole, who later memorably played Flash Harry in the St Trinian’s canon and Arthur Daley in the ’80s series Minder, and stayed with them at their shady woodland retreat, Forrigan, from 1940, when he was 15, until 1952 when he married and bought a house nearby.

In 1948, Sim was elected Rector of Edinburgh University and held the post until 1951, when his involvement in so many different film projects meant that he could no longer concentrate his full energies to the role.

But, while he was in the Scottish capital, the avid reader and polymath was aware of one of the gravestones in Canongate Kirkyard, commemorating a certain Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie – the cousin of the economist Adam Smith, who was known as a carousing, often scandalous figure in high society.

And just as Dickens changed the name slightly and created one of literature’s most famous figures, so Sim breathed unforgettable life into the part.

Yet, if the critics raved about the depth and complexity of Sim’s portrayal of a sinner-turned-saint who finds redemption at Christmas in one of the most hilarious and life-affirming sequences in celluloid history, he left them to write the tributes and explained why he didn’t talk about his work.

In a rare interview with the magazine Focus on Film, he said: “I stand or fall in my profession by the public’s judgment of my performances.

“No amount of publicity can dampen a good one or gloss over a bad one.”

And that, for him, was the end of the matter.

However, it was a measure of how seriously Sim regarded acting that he was horrified at the thought of touting products in TV commercials.

And this led to him taking action when the American food company H J Heinz started airing a series of adverts – for baked beans – that featured a voice that was remarkably similar to that of Sim (although it was, in fact, Ron Moody, who subsequently starred in another Dickens adaptation, Oliver).

The actor’s biographer, Mark Simpson, said: “Alastair was extremely annoyed.

“His first reaction was to try to stop the commercial but, of course, it was too late – it had already begun airing on television.

“Even worse, from his point of view, the adverts were very successful, so much so that he was quickly becoming the butt of many a baked bean joke.

“When Alastair entered the restaurant Simpson’s (in London), the manager came up to him and said: ‘Ah Mr Sim, I know what you want. You don’t want roast beef. You want baked beans”.

Sadly, from Sim’s perspective, the whole matter unravelled during protracted discussions over legal niceties at the High Court of Justice.

In scenes which could have come straight from an Ealing comedy, Professor Fry, an expert in “Experimental Phonetics” at London University, stated, as if he had swallowed a dictionary, that the voice (in the Heinz commercial) “had a greater preponderance of low frequencies arising from a pronounced pharyngal resonance”, whereas the voice of the plaintiff (Sim) “had more high frequency components produced by greater head resonance”.

Unsurprisingly, Lord Justice Wilmer looked perplexed at this gobbledygook and enquired of the court: “Do you know what all that means?”

He was derided as a pretentious pseud

There was a serious principle at stake here – Sim was striving to protect his acting reputation, which was most powerfully defined by his voice.

But, the next day, the court dismissed the case and he had lost.

Worse still, from his perspective, the press painted him as a precious, pompous poseur and he found himself on the receiving end of many jokes at his expense.

Heinz eventually announced that they would use a different voice in their future ad campaigns “in order that we do not step on Mr Sim’s toes”.

Sadly, the damage had been done. At the dawn of the 1960s, he found himself out of favour as social realism and kitchen-sink dramas took over the cinema.

Sim, who spent most of the 1960s working in the theatre, made several further appearances, in films such as Royal Flash and Rogue Male, but his golden era had passed – as indeed did he, from lung cancer in 1976.

Yet, for as long as people are celebrating the spirit of Christmas and revelling in the works of Dickens, they will marvel at the fashion in which this contrary Scot epitomised Scrooge. And the movies are there in perpetuity.

As one of his obituaries said: “With his general gait and gangling lope, his vast dome of a head wobbling uneasily and his sunken eyes swivelling wildly, he was the very model of a mad professor in a children’s comic.”

Yes, he was. And his gift for acting added up to considerably more than a hill of (Heinz) beans!