It’s never a good time to lose your job, but at Christmas it’s particularly harsh.

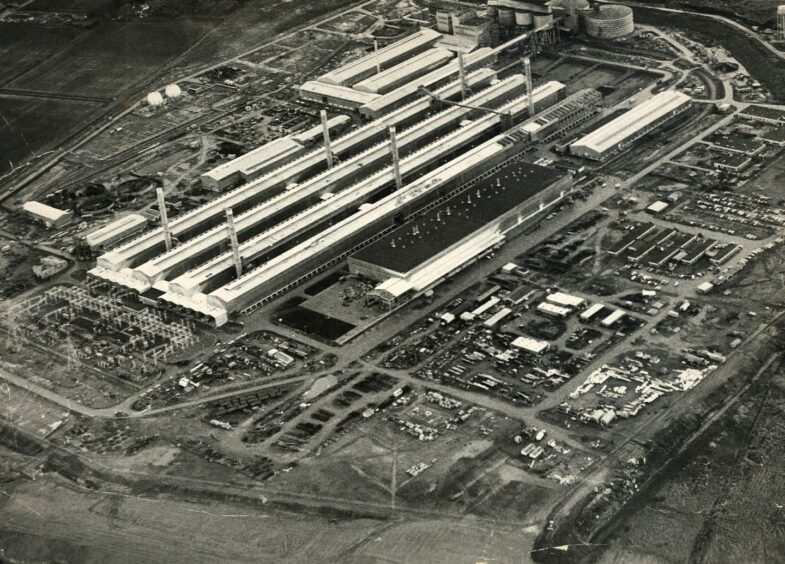

The people of Invergordon and its surrounding area were hit hard 40 years ago when, after months of denial, British Aluminium shut the door on its smelter after a mere decade of production.

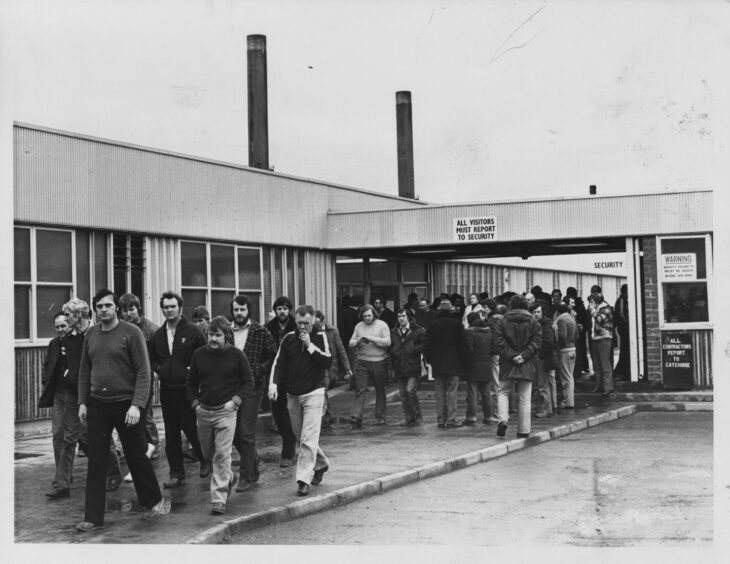

More than 900 people lost their jobs with an impact that still reverberates in the area today.

Neighbouring Alness’s population grew by thousands within months of the smelter opening, and six housing estates were rapidly built in the town to accommodate the incoming workers.

They couldn’t build the houses quickly enough – workers slept on converted cruise liners moored off Invergordon, or in wartime shelters, or even on the beach.

Invergordon smelter closure saw unemployment hit 25%

It was Scotland’s first ‘planned village’ in the new industrial world, scheduled eventually to have 16,000 people, before the rug was pulled out.

More than 600 indirect jobs were also lost and unemployment in the area shot up to 25%.

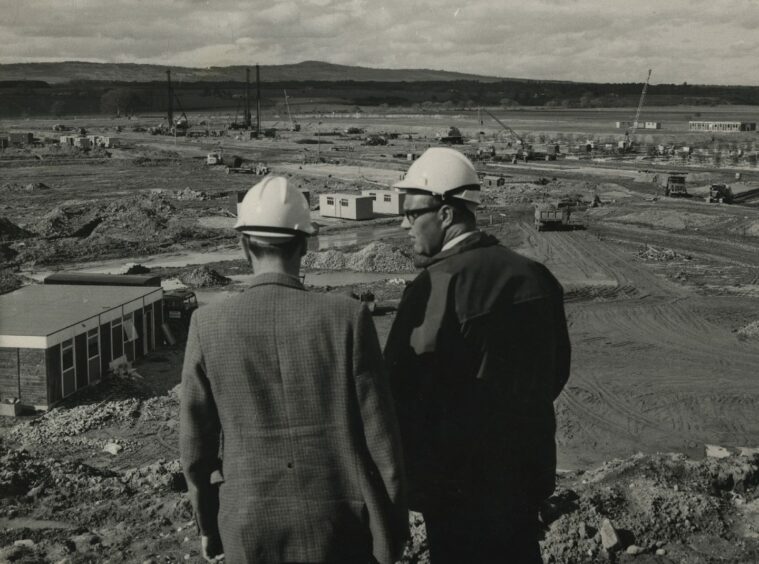

The smelter was born of an attempt by Harold Wilson’s government to cut the UK’s trade deficit.

This was in 1967, an era of cheap energy.

What scuppered it was the situation more than 200 miles away in Ayrshire at Hunterston B nuclear plant, which was supposed to power the smelter at 1.5p per unit.

Delays in the construction of the plant led to major losses, which were subsidised from the public purse by £8 million.

The problem was that British Aluminium needed £14m to stay open.

Margaret Thatcher ‘was for turning’ over smelter shutting

Government officials told then PM Margaret Thatcher on December 10 1981 that an urgent decision had to be taken, to which she replied: “I do not think we can close the Invergordon smelter at present.”

But a week later, ‘the lady was for turning’ with a minute from a Cabinet meeting from Mrs Thatcher on December 18 saying the government “should not accept Baco’s terms for keeping Invergordon” and the smelter’s closure was officially announced on December 31.

The government looked for bidders to take over the plant, but interested parties were seeking a cheap energy deal better than the government’s offer of £20m for five years.

The rescue plan was eventually abandoned on June 22 1982 despite warnings to Mrs Thatcher from Scottish Secretary George Younger that the closure would wipe out Tory support in the north.

He told Mrs Thatcher: “As I feared, this closure has provoked a degree of bitterness unparalleled even in Scotland.

“The implications of this are serious for the Highlands economically; politically they could be disastrous for us as well.”

He proved correct when Hamish Gray, Tory MP for Ross and Cromarty lost his seat the following year to Charles Kennedy.

A comment from former smelter worker Alistair MacKay of Killearnan put the debacle in perspective: “It didn’t really matter who was in power at the time. It was the fact that they had to take the power from the national grid as a condition of opening it. If they had their own power supply it would still be going yet.”

Baco denied closure rumours

Local people favoured Canadian giant Alcan, who prefer to build their own power plant to serve their smelters.

It must have been particularly galling to the families facing financial disaster that Christmas 40 years ago as British Aluminium denied the smelter would close right up to the last minute.

On Tuesday December 22, the Press & Journal reported that Baco denied closure rumours for the second time in four weeks.

A spokesman at the company’s HQ in London said the yard was working at 85% capacity, higher than any other major UK smelter, adding there had been no redundancies at Invergordon, economies had been achieved by “natural wastage”.

He attributed the rumours to the “generally depressed state of the aluminium industry”.

But the writing had been on the wall from the summer, when British Aluminium’s managing director Leslie Charles warned employees of cutbacks due to large losses at the smelter during the first half of the year and no prospect of improvement for the second half.

“Difficult decisions would have to be taken,” he warned.

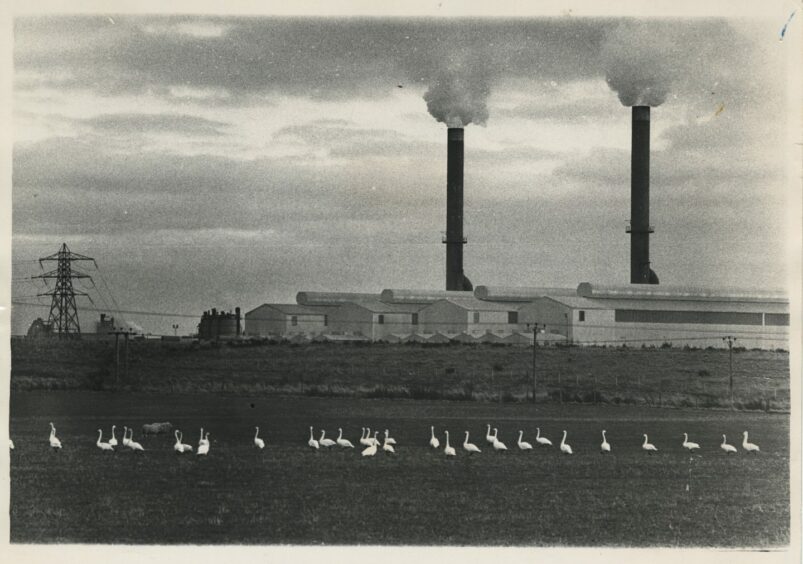

Cold, silent smokestacks of Invergordon

A few years later, the P&J’s Highland news editor Bill MacAllister contemplated the “cold, silent smokestacks of the ill-fated Invergordon smelter”.

He wrote: “Housing estates which did not exist a decade ago now have widespread headaches caused by dole queues and debts, breaking up marriages and families.

“The loss of that continuity of employment and income is still being felt on shops and services in the area.”

This was compounded by massive job losses at the Highland Fabricators yard at Nigg only a couple of years later.

The social work case load rocketed as young families plunged from prosperity to poverty accompanied by deep emotional stress.

The case load of East Ross Citizens’ Advice Bureau also rocketed as families tried to negotiate debt repayment on mortgages, hire purchase and mail order.

Then organiser Phil Durham said: “We are busy trying to persuade the companies that they cannot get blood out of a stone and that reduced payments are better than none.

“Ironically, the people who tried to improve themselves and thus took on most commitments have been worst hit as good, skilled jobs vanished overnight.”

At that point, there were 2,500 men and women unemployed in the Invergordon-Alness-Tain area.

Repercussions without end

The repercussions went on and on.

The courts were busy with repossession and arrears.

Petrol sales slumped.

Alcohol and drug abuse spiralled.

The children of unemployed workers in turn faced unemployment if they didn’t leave.

Local councillor Eileen Wilson said the area was in agony, and people felt forgotten after the spotlight during the boom times.

Nowadays, in normal times, Invergordon still benefits from handling cargo and the berthing of summer cruise liners in its harbour, with distilling, food processing and microelectronics also sources of employment.

But it’s not enough to heal the damage and compensate for the brief glory days of the smelter.