Alistair MacLean never had any pretensions about his literary talent even though many of his books became international blockbusters.

As he said: “I don’t write for myself. Many authors, if I can dignify myself and others with that term, write for themselves. I don’t. I write for my public.”

It was an attitude which served him well while he created such works as HMS Ulysses, Ice Station Zebra, Where Eagles Dare and The Guns Of Navarone.

But then, the prolific MacLean was able to draw on his myriad personal experiences when he started putting pen to paper.

After all, he was among the Allied servicemen who fought in the Arctic Convoys and helped liberate the Changi camp at the climax of the Far East campaign in the Second World War.

Arriving in a MacLean tartan kilt to begin school at Daviot Primary School, near Inverness, Alistair didn’t have a word of English in his vocabulary.

But, following the death of his Church of Scotland minister father at just 49, the family moved to Glasgow, where the young MacLean enlisted in the Royal Navy in 1941, where his searing memories of the convoys formed the basis for his visceral and atmospheric debut novel HMS Ulysses.

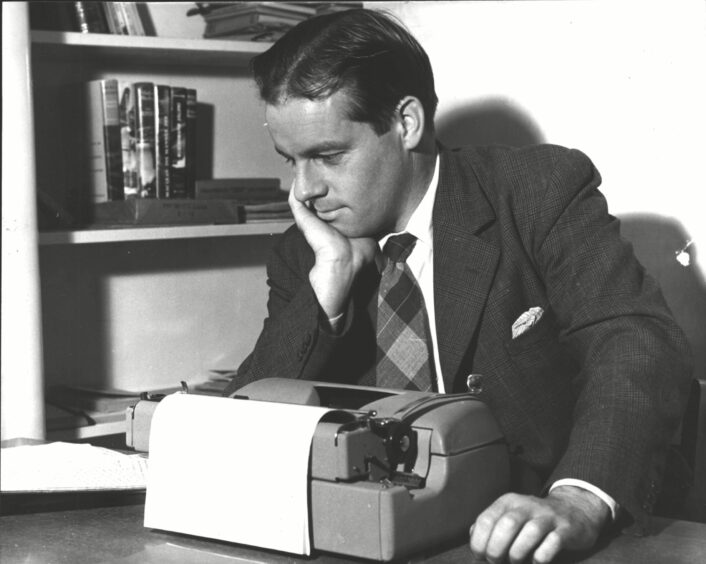

Yet he had no great impulse to start writing after becoming a teacher.

Fate, though, had other plans as he launched a new career in the 1950s.

He harboured no grand literary ambitions, but decided to enter a short story competition in the Glasgow Herald.

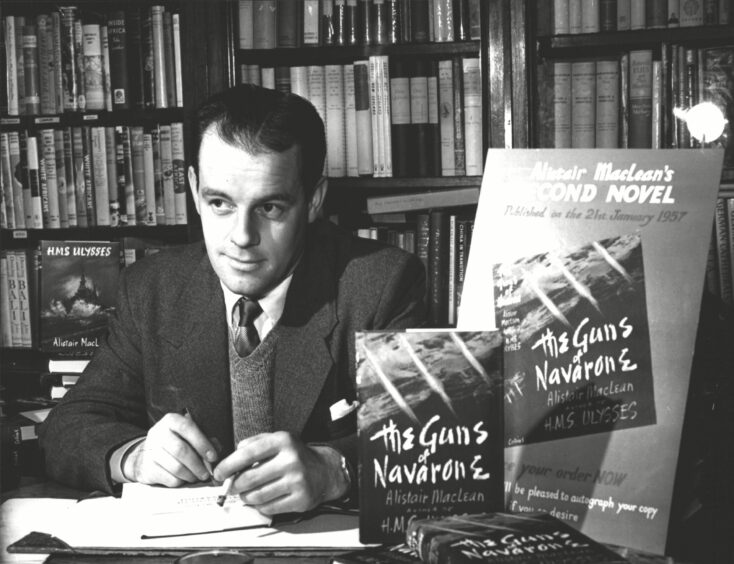

And then, from 1,000 entries, the winning tale by Alistair was published in the paper in March 1954, by which time Ian and Marjory Chapman were both editors at the Collins Books headquarters in Glasgow’s Cathedral Street.

After reading his successful submission, they were so impressed that they made contact with the author to suggest he should write a novel for their company.

But this idea was not immediately attractive to him, as explained in his official biography by the north-east journalist Jack Webster.

‘Make what you will of my book’

He recalled: “Over dinner in the city’s Royal Restaurant, the rather dour Highlander expressed little interest in writing novels, insisting that he was content with the odd short story.

“He did, however, mention his wartime experiences on the convoys to Russia, which prompted the Chapmans to enthuse about that as a subject for a book. But MacLean still showed little interest and they did not hold out much hope.

“Yet, less than 10 weeks later, they received a phone call with the message: ‘Do you want to come and collect this thing?’

“This thing. Yes, Alistair MacLean had written his book, so Ian Chapman hot-footed it to the furnished rooms at 343 King’s Park Avenue, where Alistair and his German wife, Gisela, had just had their first child.

“In the midst of a downpour of rain, Chapman was left standing on the doorstep, viewing an array of nappies while MacLean went and collected the manuscript. But then, once he was back home, he peeled open the sodden package on his kitchen table – and there was the title page of HMS Ulysses, which was destined to become one of the biggest best-sellers of all time.”

It was the beginning of a remarkable period in MacLean’s life where everything he touched turned to literary – and often cinematic – gold.

When he discovered that HMS Ulysses was being printed across the world, he wondered whether it would earn him enough money to enable him to put down a deposit on a new house at Hillend Road in Clarkston.

A few million book sales later, it was the last thing he had to worry about.

Soon there were plenty houses for him

A new BBC Alba documentary, to be screened on December 28, has examined his astonishing story, which could come straight out of a novel both in terms of his belief he was a better writer in Gaelic than English and the often tempestuous nature of his personal life away from the typewriter.

For instance, Where Eagles Dare was turned into a smash-hit movie, starring Clint Eastwood and Richard Burton, but he and the Welshman did not always see eye to eye, which led to a spectacular punch-up between the duo.

The setting was the Dorchester Hotel in London’s Park Lane. And although Burton, on screen, was accustomed to shoving his weight around, it was a different matter when he squared up to Alistair during a drunken brawl.

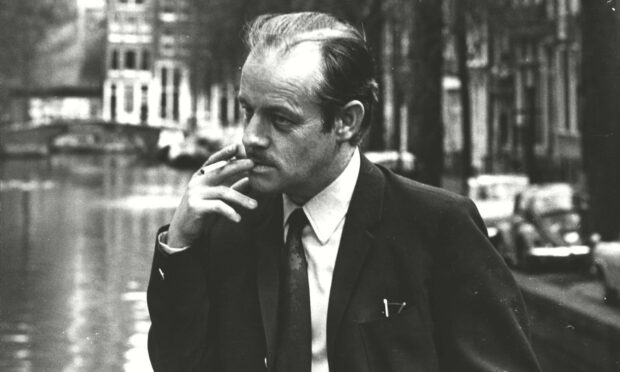

The peripatetic author, who lived in different parts of Europe throughout his life, may have been slightly-built, but he landed a powerful right hook to Burton’s nose, sending him sprawling into unconsciousness.

There was a poignant epitaph to that acrimonious encounter when after the death of both men, MacLean aged 64 in 1987 and Burton at 58 just three years earlier, the duo were buried at the same cemetery in Switzerland.

Jack Webster travelled to Celigny to meet Gisela, and that was the prelude to an evocative afternoon for the pair.

He later recalled: “She asked me if I would like to see Alistair’s grave. So we wandered along to the cemetery, an unpretentious little place where the first grave on the left might well have belonged to a local labourer, except for the fact that the headstone told a different story: Richard Burton.

“Across the narrow pathway, just a few yards away, we came upon that other stone, marking the last resting place of the warm, wayward, fallible human being: Alistair MacLean.

“And there they lie in peace forever, near a waterfall which tumbles down a little ravine like a sparkling Highland burn.”

MacLean was a keen yachtsman who explored the west coast of Scotland and celebrated his Highland heritage in his 1965 novel When Eight Bells Toll.

The film of the book starred Anthony Hopkins and was dramatically shot in and around the Clan MacLean stronghold of Duart Castle on Mull.

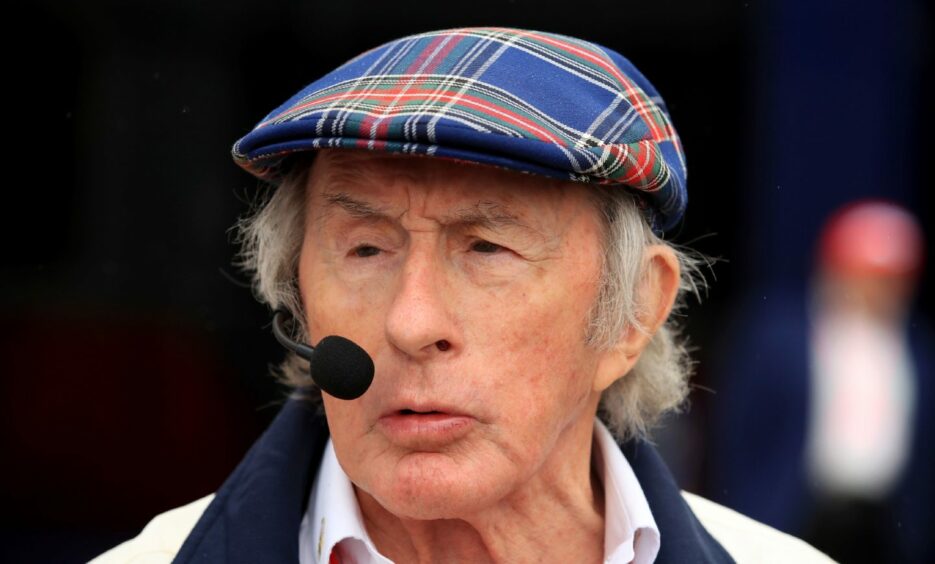

The programme features archive film which records a meeting between the writer and three-time F1 motor racing world champion Jackie Stewart about a movie which Alistair was planning with his compatriot as the star.

But sadly, the project never came to fruition, and a MacLean movie with Stewart in the lead role is one of the great ‘what ifs?’ of Scottish cinema.

The documentary’s director, Les Wilson, has delved into the many different strands of one of Scotland’s greatest page-turners.

He told me: “I was a huge fan of MacLean’s books and films as a teenager but had really forgotten about him for decades.

“It has been a delight rediscovering him for this production. A wet Sunday afternoon or a winter evening is well-spent in his company.

“He is a master story-teller and, as we discovered while we were researching his life, a fascinating man with a very interesting story of his own.”

Alistair’s niece, Shona MacLean, herself a successful author, appears in the new programme and has spoken about her memories of her uncle.

She said: “From these early visits, I remember a small, quiet man who dressed just like my dad and who seemed out of place with the paraphernalia and fuss around him.

“It was as a teenager that I got to know him better. He seemed to come home to Scotland more often in the last decade of his life, and we went on holidays to visit him in Cannes and then Dubrovnik.

“There would be large dinners at night – I distinctly remember being struck, at about 17 early in a holiday in Dubrovnik, that people around the table were talking about food as if it were art or great literature, rather than ‘very nice’, ‘too salty’ or ‘a bit dry’.

“I had never heard people talk about food this way before.”

She continued: “On one occasion, my sister and I had had to smuggle two pounds of mince from our local butcher for him, and a packet of pork sausages, into Yugoslavia in our suitcases.

“Uncle Alistair’s friend Avdo, a former hotel manager whom he employed to look after everything and whose house overlooked a beautiful inlet of the Adriatic where he lived, ensured that everything went smoothly at the airport.

He offered some invaluable advice

“However, being summoned to be interrogated was daunting. When my parents brandished my school report at him one year, when I had done very well in English, he asked me if I wanted to be a writer.

“He then gave me one of the best pieces of advice I’ve had – ‘If you write something and an editor tells you to change it, you change it. I never change anything, but that’s because I’m me – you change it’.

“My uncle died years before I eventually started to write, but when I was working on my own first book, I wondered what kind of readership I was writing for. And I realised I was writing something that I hoped my father and his brothers, who had been brought up on Walter Scott, John Buchan and Robert Louis Stevenson, would have liked.”

The Adventures of Alistair MacLean is on BBC Alba on December 28 at 9pm.

More like this:

John Buchan walked The Thirty-Nine Steps to the Freedom of Perth

Alastair Sim: The many faces of the Scot who remains the screen’s finest Scrooge

Die Hard: Is iconic action hero John McClane really from Scotland?