“Acres of blindingly yellow gorse or broom in the spring, azure blue sea and sky in the summer and architecturally amazing snow drifts in the winter… honeyed aromas from heather and bog myrtle, bike runs in the warm, apricot glow of the setting sun.”

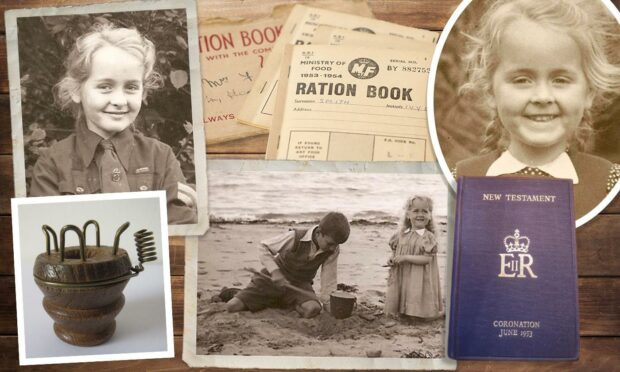

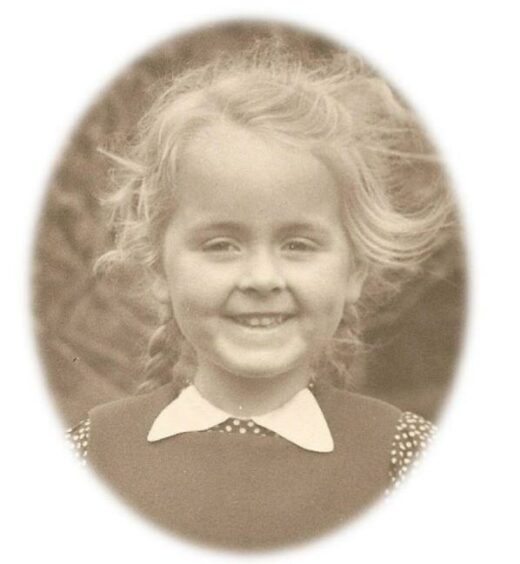

A flavour of Marjorie Kelman’s (nee Fulton) new book, which reminisces on her post-war childhood as a daughter of the manse in Helmsdale, Sutherland.

Marjorie has captured her enchanting memories in a little book which will resonate with anyone who grew up in the Highlands in the late ’40s and ’50s.

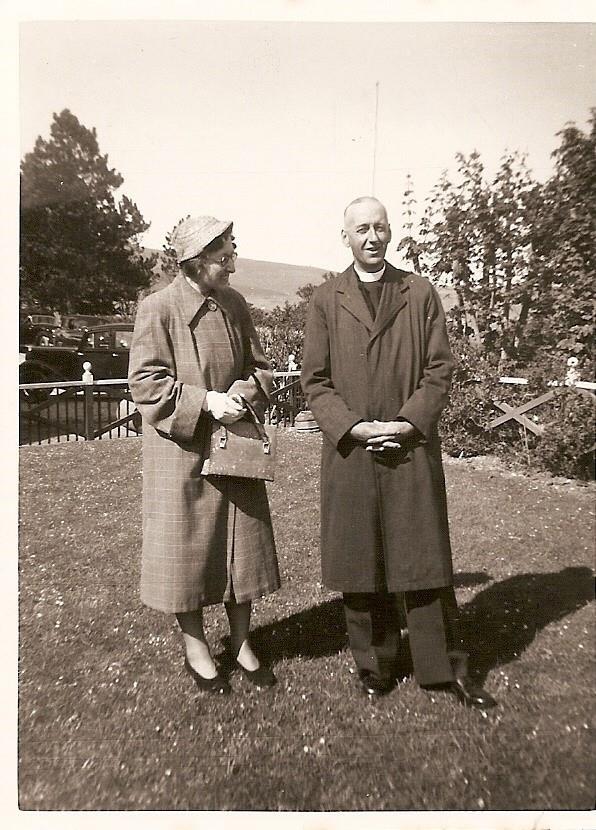

Her father John was a Church of Scotland minister, serving in Arran when Marjorie was born, then in Clarkston, Glasgow until she was five, in 1948.

Then came the move to Helmsdale, where Rev Fulton became the minister in Kildonan and Loth.

This was familiar territory for Marjorie’s mother Peg, who had been born in Thurso, with Macpherson forebears from the remote Kildonan parish of Griamachary.

The young Marjorie found much to get used to in her new life.

There was no electricity, so as in all Highland and island homes of the time, Tilley lamps, with their comforting hiss, illuminated her evenings.

“Getting a Tilley to work involved having a jar of methylated spirits in which a small gadget would soak before being attached to the lamp below the mantle, pressure had to be pumped and and in due course the most brilliant white light emanated from the glass globe,” writes Marjorie.

A Rayburn made the kitchen the only warm room in the house and the hub of the household.

“It is where we sat for meals, where the sewing machine chugged through miles of cloth, where the ironing was done, meals prepared, baking produced, fish filleted, mounds of summer fruits cleaned and weighed, and homework studied.”

Marjorie found Helmsdale school ‘old, dingy and very old-fashioned’ after her bright modern school in Glasgow.

She remembers tiered desks with slots for slates and a groove for pencils.

The three Rs

Mrs Chisholm worked the class hard, with much chanting of times tables, spelling by rote and complicated arithmetic.

When Marjorie was in Primary 7, the school moved into a new building.

She remembers: “It smelt of paint, polish and new flooring, had showers off the gym hall and a fully furnished flat for the use of the domestic science department, teaching girls how to look after a home!”

No more slates, now writing was done with pens dipped in ink: “The teacher first had to pour a little ink into the individual inkwells from a big glass jar with a spout.

“More often than not the ink would be spilt and the teacher’s resulting bad mood made us all extra anxious and therefore more likely to make a mess in our jotters.

“These pens scratched and scraped, the nibs were often past their best and somehow we would get blots of ink everywhere, no matter how hard we tried.”

There were visits from the nit nurse, and checks for impetigo which was treated with eye-catching gentian violet.

Blessed with a good singing voice, Marjorie was the visiting teacher’s pet.

“Our teacher used to get violently angry when the other children just could not understand what he was trying to teach, and frequently would throw a wooden-backed blackboard duster across the room in rage. It never hit anyone!”

Rude words

The P7 encyclopaedias were scribbled on with ‘the rudest words imaginable.’

“I often wondered if the teacher knew these were there and decided just to ignore them or whether she was completely unaware of their existence,” said Marjorie.

In 1955, Helmsdale hit the headlines when the north suffered two intense snowstorms in January and February.

Marjorie remembers how Operation Snowdrop swung into action, involving the armed forces, police and health service.

“Helicopters came to the fore, with pilots looking out for giant letters marked out in the snow, for example: D for medical help, F for food and C for cattle fodder, a large H was also used as a signal for aid.

“What a thrill we had when a helicopter landed in the Castle Park close to our house. We had never seen one before.”

Notable visitors to Helmsdale

Memorable visitors included the Prime Minster of Canada, John Diefenbaker in 1958, causing much excitement, especially when he and his entourage attended Marjorie’s father’s Bunillidh Church.

“His forebears had originally come from the Strath of Kildonan where whole families were ruthlessly evicted in 1813 so that the land could be used solely for sheep.”

Marjorie remembers her father reciting part of The Canadian Boat Song, “a very few lines which reflect the dreadful sadness of those who were so cruelly hounded out of their homes, which were then set on fire before their eyes.”

A frequent visitor to the church was the then Princess Royal, Countess of Harewood, aunt to the present Queen.

“She was very unassuming and blended insignificantly into the normal congregation,” Marjorie remembers.

Marjorie was a Brownie and Girl Guide, and particularly thrilled by one special visitor, World Chief Guide Lady Olave Baden-Powell.

“This was an amazing visit for she was outstandingly famous. Just imagine her coming to Helmsdale!”

Marjorie’s vivid memories look back at a time when people had less money, and kindness, resourcefulness and ingenuity were the backbone of her happy childhood.

Copies of Memories Of A 1950s Childhood In Helmsdale by Marjorie Kelman are priced at £7.50, and can be bought from Timespan in Helmsdale, the Clyne Heritage Society in Brora, the Dornoch Bookshop, or directly from Marjorie.

She can be contacted by email (marjorie.kelman@googlemail.com) or on 01224 321633 and is happy to pack and post at £10 per book.

You might also like: