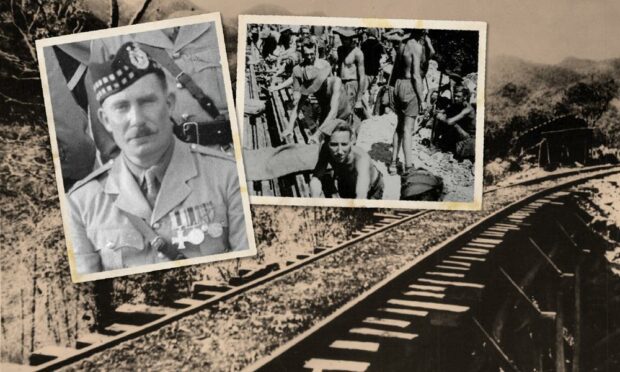

A mere six weeks after Japan was defeated in the Second World War, a senior officer of the Gordon Highlanders gave a devastating interview to the Evening Express about his experiences as a POW on the infamous Burma railway.

Lt Col John (Jack) Heslop Stitt pulled no punches in describing the vicious cruelty of his captors and the gruelling ordeal meted out to the POWs.

He described physical beatings, psychological cruelty, primitive sanitation, poor food and sickness, including cholera.

Stitt had been serving with the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders in Malaya when his battalion became prisoners of war after the fall of Singapore.

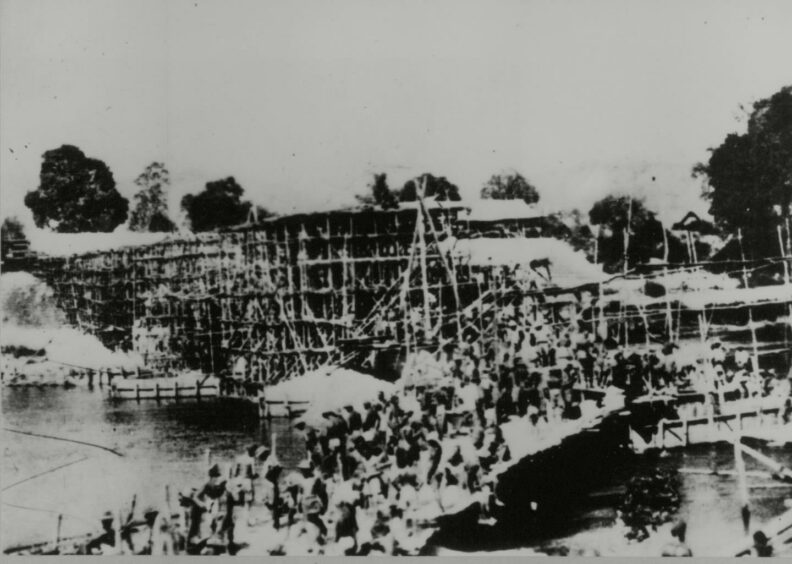

The Burma railway – also known as the Death Railway – began construction in 1942, to take troops and supplies from Siam – now known as Thailand — to the Burma war front.

The terrain was harsh, hilly jungle, already rejected as too difficult for a railway by British-ruled Burma in 1885.

But the Japanese decided that it had to be done to avoid a dangerous 2,000-mile sea journey round the Malay peninsula, through the Strait of Malacca and Andaman Sea.

The route was from Thanbyuzayat in Burma 69 miles to the Thai border, and 189 miles through Thailand to Ban Pong.

Work began at both ends in late 1942 and was completed – in what is an astonishing feat – a year later.

Up to 250,000 civilian labourers worked on it, along with 60,000 POWs.

The rate of attrition was massive — 90,000 civilian labourers died, and more than 12,000 POWs.

The experiences of the POWs who worked on it are immortalised in the 1957 eight times Oscar-winning epic, Bridge On The River Kwai.

But despite the undisputed power of this film, there’s something strikingly raw in Col. Stitt’s account, given not long after he reached home turf in October 1945.

Jack was made of strong stuff, having been through the First World War and come out with a Military Cross.

He had joined the Gordon Highlanders 7th Battalion early in 1917, and earned his MC at the Battle of Arras that April for taking a number of prisoners.

He was wounded a few days later and invalided back to Britain, ending his war.

In the inter-war years he continued his military service, climbing through the ranks and serving in different battalions throughout the world.

In January 1939 he returned to the 2nd Battalion, now in Singapore, as second-in-command.

Command position building Death Railway

He took over command of this battalion in December 1941 shortly after the outbreak of the war with the Japanese.

The Gordon Highlanders were part of the Singapore Fortress Garrison so were not deployed to fight the Japanese Army until January 25 1942.

But three weeks later came Singapore’s surrender, and the whole battalion became POWs.

Jack was languishing in Changi jail in Singapore when he was put in charge of a battalion of POWs comprising Gordons, Manchesters and Loyals, and sent to Siam.

They were to construct the Nonpladook to Tan Baziat section of the railway, building four and a half miles of embankment and several bridges.

“In our first camp at Chundkai, where we arrived on October 30 1942, there were about 5,000 men,” Col. Stitt said.

And in stiff-upper-lip-style understatement, he went on: “Conditions were not too good.

“Sanitation was primitive, food was poor and we were all working very hard; out before daylight, and back after dark.

“Quite a lot of men went sick.”

Medical attention came at a cost.

“If the doctor examined a man and pronounced him unfit for duty, he promptly received several hefty blows on the side of the head from a Japanese officer, and then (was) taken off to work.”

Once they started hitting you they go mad and don’t seem able to stop.”

Jack Stitt

In parties of 100 men, the task was to excavate two thirds of a mile each week.

It fell to Col. Stitt, as the officer in charge, to go out with the Japanese engineer officer to measure the ground.

“If the amount was finished in six days they had the seventh day off.

“If it wasn’t the men were chased to hell and I and the chaps in charge of sub-units were given a beating.

“Consequently in an effort to get the day’s holiday, many men over-worked themselves during the week and in their weakened condition (malaria and other sicknesses) the strain killed a lot of them.”

They moved camp in January to Barnkow, doing the same sort of work.

Here, conditions were even more brutal, with commanding officers like Stitt frequently beaten up in front of their men.

“Once they started hitting you they go mad and don’t seem able to stop,” he said.

Once that phase was finished, they marched 108 miles to another camp, where the treatment got even worse.

“There was no proper accommodation at all in this ‘camp’, just a few old tattered tents and the rest of us were out in the open to fend for ourselves.

Monsoon misery

“The monsoon was on and it was raining every day so we made huts for ourselves.”

The men were in a bad state by this time.

“There were no washing facilities at the camp,” Col. Stitt went on.

“Our clothes had worn out and the Japanese would not issue us with replacements.

“Most of us were wearing a garment that rather resembled a G string.

“We called them ‘Jap nappies’.”

In June cholera broke out, and with few medical supplies 100 out of 800 men died in their camp.

There was a highlight in August 1943 when the men received their first letters from home.

It would be another nine months before they received any more mail.

“We had so far been allowed to send two printed postcards home,” said Col. Stitt.

“There were the usual things — My health is (A) excellent, (B) fair and (C) poor.

“There was no coercion from the Japanese as to which two words you crossed out, but I’ve never come across anyone who’s health was not ‘excellent’ even when the men were at death’s door with cholera.”

The treatment of sick men in hospital camps was vicious, with the Japanese medical officers bartering treatment for wrist watches.

The railway was finished in November 1943, with a great ceremony and the driving in of a solid gold last stake.

“It was probably solid brass,” Col. Stitt said.

After his stint on the railway, Col. Stitt went to Kanchanaburi Camp in Thailand between August 1944 and August 1945.

The men were ordered to change camp again, and taken by train to Bangkok, segregated this time, with the officers supposed to go to a different, new camp.

“We arrived at Bangkok and the officers were met by a Japanese officer who told us the war was over.

“The news spread like lightning and for a moment we were all stunned.

“Then, spontaneously, 200 British officers sang God Save The King on Bangkok station with thousands of Japanese soldiers staring at us sullenly with despair written on their faces.

“It had been a tough year in Siam but I think, for the most of us, that moment made up for a lot.”

From the outbreak of hostilities until the Japanese surrender, in August 1945, 380 men of the battalion lost their lives, approximately 40%.

History doesn’t record Jack’s state of health or mental well-being on his release, but his ordeal wasn’t going to hold him down.

He went almost immediately to the vaults of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in Singapore where he was able to recover the 2nd Battalion colours and silver which had been lodged there in 1941.

He returned to the UK with both aboard HMS Nelson.

For Jack, one of the greatest tragedies of the Death Railway was how many men ended up maimed and crippled for life through lack of medical supplies.

“In that country if you even got a slight scratch from a bamboo thorn it turned into a septic ulcer before you realised it.

“I’ve seen men with ulcers that had spread right round their feet and not an inch of bandage to wrap it up with.

“Altogether, over 200 men had legs amputated in Siam.”

Prisoners, either taking them or being one, were a marked theme of his military career, for, on his return home, Jack was put in charge of a POW Camp 63 at Balhary estate, Perthshire.

He retired from the Army late in 1948.

Afterwards, Jack ran a popular alpine nursery in Blairgowrie, becoming a well-known local figure.

He died in 1988 and his ashes are interred in Aboyne cemetery alongside his wife and parents-in-law.