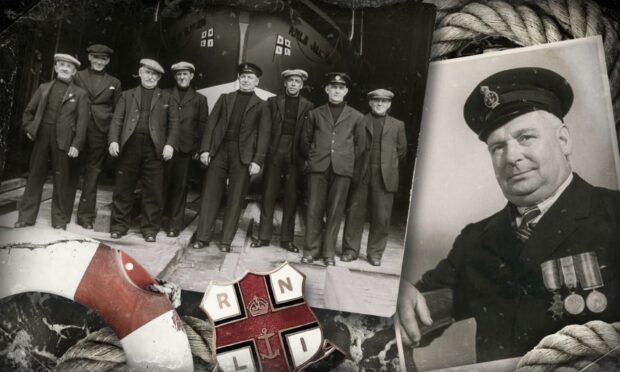

They were the north-east Scots who sailed into the teeth of a gale to save stricken sailors – and then, once they had made their first trip, continued their missions of mercy again and again and again.

A blizzard was raging throughout the repeated efforts of Peterhead’s RNLI volunteers as they faced a series of gruelling challenges from January 23 to 26 1942.

Yet despite the appalling conditions and the storm-tossed seas one of them later described as “a nightmare”, their determination to help those in peril never wavered as more than 100 men were rescued.

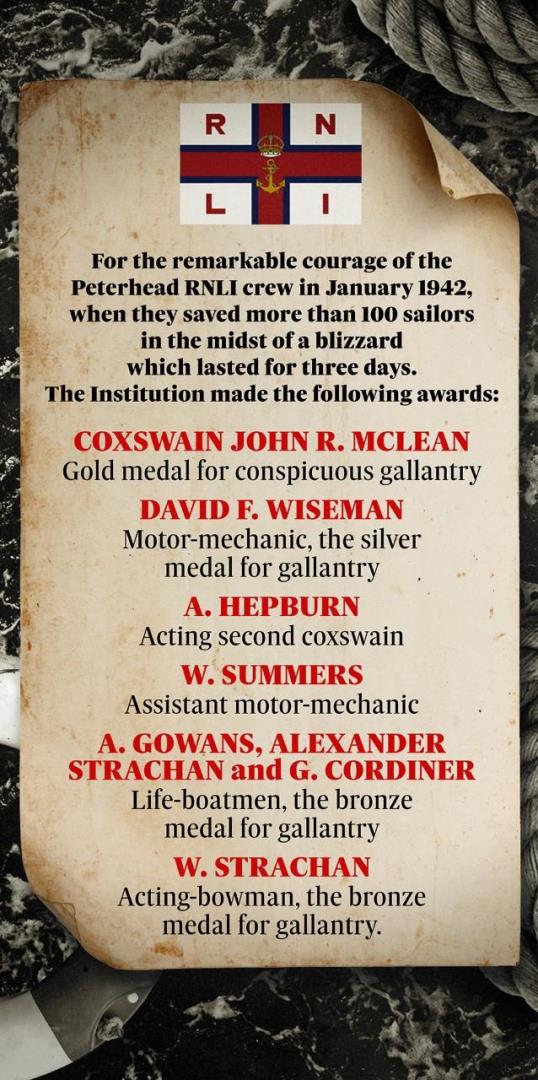

In the aftermath of their labours, coxswain John B McLean was presented with the Lifeboat VC.

It was the first time for 104 years that such an honour had been conferred on a lifeboatman in Scotland.

The Duke of Montrose, who visited the Blue Toon that summer to celebrate the crew who ventured into several desperate situations without any regard for their own safety, said: “It was service by the brave for the brave”.

This was astonishing courage

The drama began at 6.40am on January 23 when a message came from the coastguard that the SS Runswick, of Whitby, had been involved in a collision.

The steamer was struggling eight miles off Peterhead, and the motor lifeboat Julia Park Barry left the port at 7.50am.

The men were confronted by scenes of chaos but the Runswick, which had been severely damaged about the bows, was escorted into Peterhead Bay.

Two other steamers, the SS Saltwick, of Whitby, which had also been damaged, and the SS Fidra, of Glasgow, followed to seek shelter.

They arrived at 12.30pm under the direction of the harbour master.

But with the weather deteriorating, an anxious watch was kept on the three steamers, because if their anchors failed to hold, they would crash into rocks.

For the next 12 hours, the crew stood by. At 12.30am on Saturday, they heard and saw signals of distress and the lifeboat put out at 12.50.

The wind had risen and the temperature had plummeted. It was blowing a gale, with a blinding snow-storm.

As he and his colleagues left the harbour in the darkness, Mr McLean could see no further than the length of his boat.

He made his way across the bay and spotted the Runswick. She was already foundering on the rocks, lying on her port side with the seas breaking over her.

The lifeboat went under her quarter, threw a rope to the crew and hung on with great difficulty in the huge swell.

The rope broke on four occasions and another attempt had to be made.

Mr McLean kept the engines running to relieve the tremendous strain on the ropes but massive waves crashed over the steamer and the lifeboat.

The work was all the more difficult because the men were exhausted, but the whole crew of 44 were rescued.

The lifeboat returned to harbour and arrived back in the early hours on Saturday January 24.

But although the crew had already been on duty for 19 hours and were exhausted from their exertions, there was still plenty more work to do.

In what was now the third day of the gale, the blasts were at their fiercest.

The gusts reached speeds of 105mph and they wreaked havoc.

At 8am on Sunday January 25, the coxswain was once more on watch and, two hours later, a second steamer, the Saltwick, went ashore.

She was close to the harbour, and the coastguard’s life-saving apparatus sped to her assistance.

The vessel’s crew were told to stay on board until the weather improved, but six of them launched a raft in what proved a terrible misjudgement.

It tossed about like a toy craft between the steamer and the shore for an hour and when it touched the beach, the sailors were thrown into the heavy surf.

The battle with the elements raged on

Serving personnel went to their rescue and eventually succeeded in seizing all six and bringing them ashore, but two of them were dead.

This happened in front of the house of the honorary secretary of the lifeboat station, and he and his wife took the men – some of whom were delirious – into their dwelling, provided them with hot baths, food and clothes, and did everything possible for them until they could be taken to hospital.

At 4pm, the third steamer, the Fidra, went ashore and, at 7pm, sounded the SOS call on her siren.

The lifeboat’s crew received a message from the coastguard and the coxswain marched swiftly to observe the vessel from the shore, and make certain of her position before he set sail.

In the darkness, he could just detect the loom of the steamer. But then, a naval signalman was told in a message from her master that she was breaking up and that, unless help came at once, he and his crew would all be dead.

On the brink of tragedy

In such dire straits, the lifeboat was soon on its way. The harbour’s defence searchlight was turned on to help Mr McLean and his confreres and the wind had eased a little, but the weather was still atrocious.

When they reached the Fidra, she was almost submerged and the Peterhead men rushed to her assistance.

As they did so, a heavy swell engulfed them, breaking over the steamer, and nearly swallowing up the lifeboat with it.

Mr McLean despatched a line aboard the steamer’s boat-deck, where the crew of 26 men were huddled.

The rise and fall of the seas was terrible and he recalled: “It was a nightmare to keep her from being flung on to the steamer “.

But he thrived under pressure, and every time the lifeboat swung close, men leapt aboard.

One had sprained his ankle and could not jump, but as the emergency vessel moved towards the steamer, they snatched him to safety.

The lifeboat was alongside for 50 minutes and then, with the whole crew rescued, it returned to harbour. Its entrance lights were switched on and she arrived back at 3.15am.

The crew moored her and went home for dry clothing, but they realised they might be needed again if the Saltwick required assistance.

Men continued their heroics

There was scant respite. At 8.30am, a message came from the senior naval officer, asking the lifeboat to save the Saltwick’s crew from further exposure.

It was now light, and the steamer could be witnessed lying on the beach, on her starboard side.

The only way to approach was between her and the shore and it was a treacherous operation.

The RNLI archive records: “There was a ridge of rock close to it and the lifeboat struck it. Then a great sea came in, lifted her almost out of the water, and flung her on to the rock.

“The sea struck again, washed the second-coxswain from stern to bow, and nearly carried him and several other members overboard.

“The coxswain went full speed astern to clear the rock, and, with the seas striking her at the same time, she was carried round the steamer’s bow to the shoreward side. Here, he found deeper water.

Peterhead lifeboat crew tired and hungry

“Thirty-six of the Saltwick’s crew were rescued, but the master and three officers remained on board. As there appeared to be more water at the steamer’s stern than her bow, the lifeboat came out that way. Twice, she struck rocks, but got clear and came safely into harbour.”

By this stage, it was 11am on Monday, a little matter of 75 hours and 27 minutes since the rescue vessel had originally gone out to the Runswick.

During the previous 27 hours, the crew had eaten very little food and been offered no chance to rest. They were shattered.

Altogether, they had been out in a tempestuous gale and bitter cold three times, twice in pitch darkness and blinding snow, and had rescued 106 lives.

The lifeboat herself had been damaged, first against the Fidra and then, more severely, on the rocks among which the Saltwick lay.

Six feet of her fender had been destroyed, but that could be – and was – repaired.

A huge credit to their community

Ultimately, the crew had risen above and beyond the call of duty and been at the heart of one of the greatest rescues in the RNLI’s history. And their remarkable courage still resonates today.

Jurgs Wahle, the current operations manager at Peterhead Lifeboat Station, told the Press & Journal: “As we approach the 80th anniversary of three extraordinary services where 106 lives were saved, the feat is more extraordinary considering the very basic vessels and equipment of the 1940s.

“When thinking about the horrendous weather and sea state, it is truly humbling that the coxswain and crew showed such bravery and tenacity with little respite or time to rest.

“The willingness of the Peterhead crew to risk everything in their bid to save lives is an inspiration to all of us at the station.

“Eighty years on, we are incredibly proud of their legacy and strive to emulate their bravery, teamwork and seamanship as we crew our lifeboat today.”

More like this:

Oil tanker in peril: When ecological disaster was averted at St Kilda in 1981

A monument to Moray: New book a love letter to Lossiemouth’s fishing past