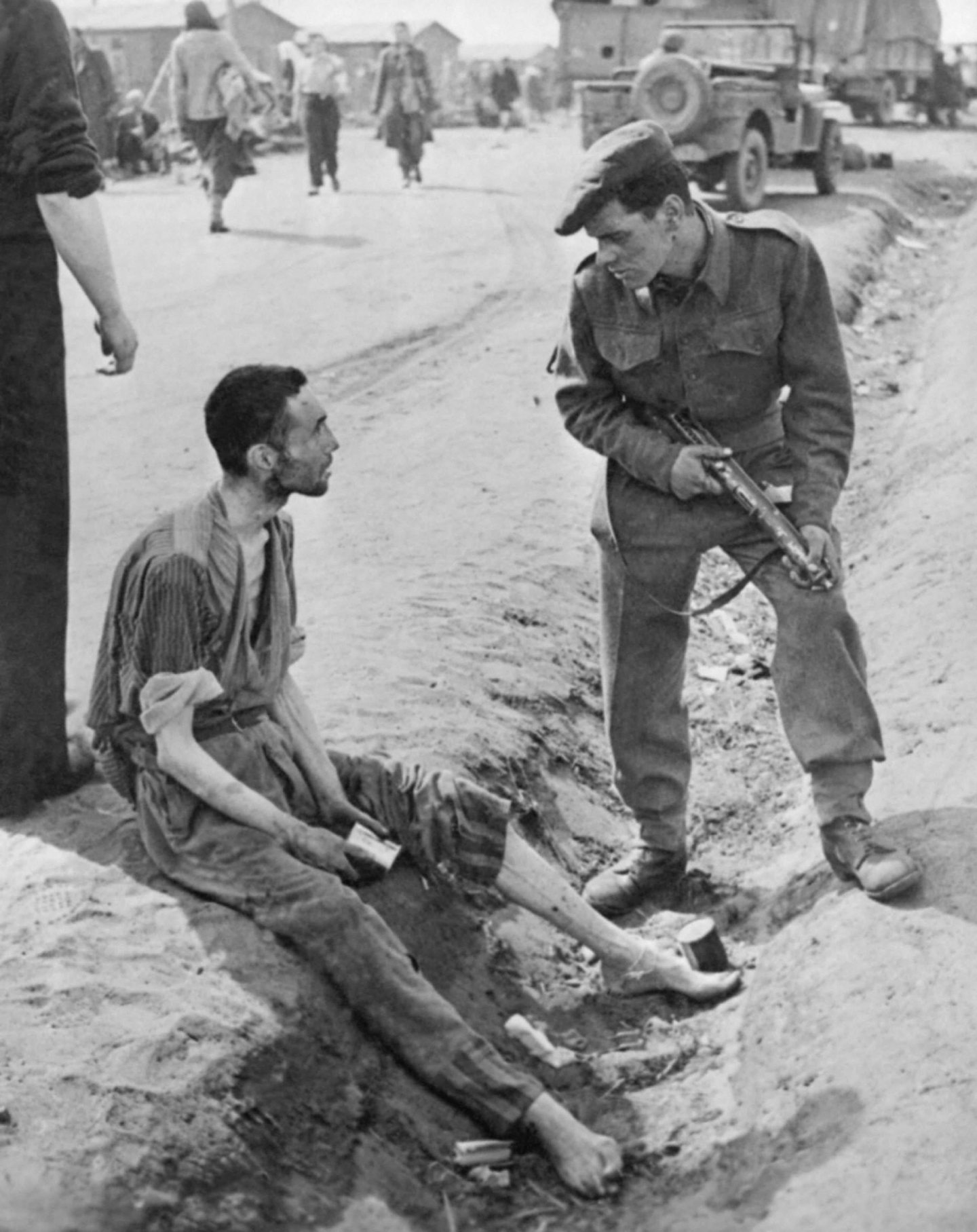

Mere words can never adequately describe the scale of atrocities committed at places such as Belsen during the Second World War.

Dr Alexander Michie, from Durris on Deeside, was the first British medical officer to enter the infamous camp in April 1945 and the scenes of squalor, death and degradation he witnessed rendered him mute on what he saw there for many years.

How could he portray the visceral horror, the sickening smell, the rampant disease and emaciated despair of a place that has become synonymous with man’s inhumanity to man, woman and child, and where tens of thousands of people perished at the hands of their Nazi captors?

Yet shortly before his death in 1995, Dr Michie sat down with his son, Alistair, and recorded his thoughts and memories of walking into the real-life equivalent of a Dore painting of hell and reacting to a scale of malignity, malnutrition and misery which no human should ever have to endure.

We have been given a transcript of the lengthy conversation Alistair shared with his late father and are honoured to reproduce parts of the contents in the build-up to World Holocaust Day on January 27.

BBC broadcaster Richard Dimbleby described the almost unimaginable horror that greeted him as he toured the Nazi concentration camp shortly after it had been liberated by the British in April 1945.

Bergen-Belsen was originally created as a prisoner of war camp but was used by the SS for Jewish inmates from 1943 onwards.

It is estimated that between 70,000 and 80,000 people died there in the space of two years.

Dimbleby was the first broadcaster to enter the site and, understandably overcome by emotion, broke down several times while he was making his report, which is all the more ghastly because of his clipped, civilised tones.

The BBC initially refused to screen it, as they could not believe the carnage he had described, and it was only aired after Dimbleby threatened to resign.

But, behind the scenes, Dr Michie was involved in the thankless task of trying to bring relief to people beyond help and find food, medicines and clean water in an environment where they simply didn’t exist, and where, if he couldn’t assist in some of the worst cases, at least ease their torment.

He recalled: “The finding of food wasn’t my business, that was the business of the supply people, but I had the job to try and recommend a sort of gruel, which was a pretty low-calorie mix with as much milk in it as we could get and wheatmeal, oatmeal, whatever we could find.

“And then I recommended to this committee that we must get the bulldozers in because the only way to get rid of these bodies were graves, and they were brought in and they were filled up just as they were being opened up.

There were no words to describe what we experienced and saw.”

Dr Alexander Michie

“There were many thousands (of bodies). I don’t think that I exaggerate if I say there were six to eight thousand bodies lying in huts and around the huts.

“They were so desperate for food; I remember there was a huge pile of boots and shoes and that sort of thing which had been taken off prisoners.

“I can remember half a dozen people (in a room) chewing the soles of boots, to see if they could get any nourishment out of them.

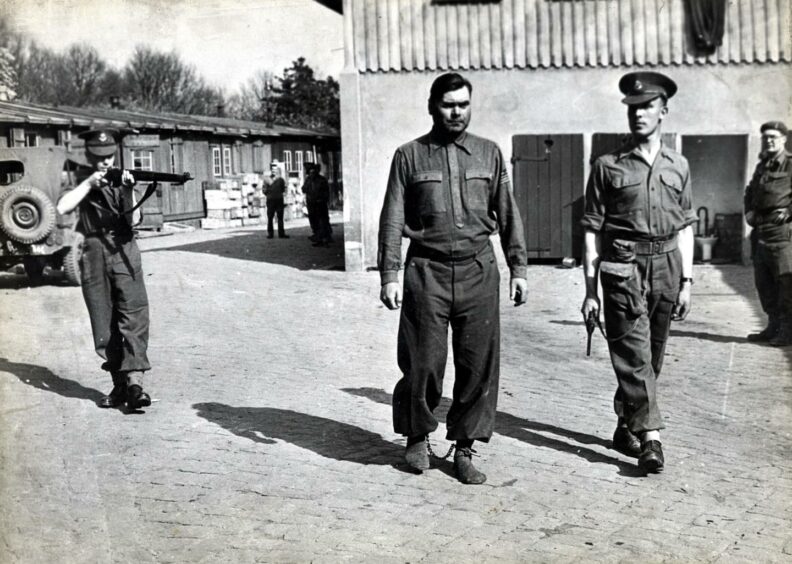

The German guards had to help

“I can very clearly see one of these British gunner boys, an officer, who was in charge of some trucks with SS guards, loading the bodies on to the trucks.

“And one SS fellow downright refused to have anything further to do with this, and he started to run away from the British gunner who had his gun; and he shot him right through the head.

“That settled the Germans completely.”

Dr Michie strove to improve the ghastly situation and it’s obvious that he made a positive difference, once April moved into May and thence to the summer, when he and his colleagues were bolstered by fresh supplies arriving, as the enormity of the crimes committed against the prisoners was laid bare.

But it took its toll. By the stage he returned to the north-east of Scotland to be married in August 1945, his fiancee Nora could hardly believe how much he had changed and thought that he looked “like an old man”.

There already was a tragic backdrop in his personal life.

In 1940 Dr Michie had married Margaret Stewart but he was given compassionate leave to return home when his wife developed Hodgkin’s disease.

She died aged 31 in September 1943, six months after giving birth to Alistair’s sister, Sheila.

The doctor was distraught and threw himself into the preparations for D-Day, starting at Catterick Camp, as the prelude to landing in Normandy, where his public health skills won him a military OBE.

His task was to advise on how to keep a Corps in action while it was crossing the Seine in the midst of a typhoid outbreak among the troops.

He was an expert in his field. But nothing could have prepared him for Belsen.

As Dr Michie said: “We had to get them (the surviving prisoners) fed, we had to get the dead buried, we had to try and prevent disease spreading.

“We had to de-louse the people because typhus was rife, and the (Allied) troops were at very great risk.

“In fact, we powdered all the troops with DDT, which today would be regarded as the wrong thing, but it was the right thing at that time and I don’t think we had many secondary cases of typhus.

“But I remember the mayor of Celle (a town just a few miles from Belsen) coming to the camp.

“He was brought up and taken round and I can still see that man in a jeep with the tears streaming down his face.

“I don’t think that he really realised just what things (had been happening at the camp) and what was going on.

“And they told me what he was saying was: ‘The shame of it, the shame of it’.”

Nobody was immune from the devastating impact of Belsen.

As Dr Michie told his son, even battle-hardened brigadiers and generals who had seen death and destruction on a massive scale through their years of service were shocked to the core by the fashion in which thousands of people had either been systematically exterminated or left to succumb to starvation or illness.

He said: “(There was) this brigadier who came up one day and I had to take him around and show him what was what.

“And this fellow, with disease all around him, was scared to tears, and here was a fellow who could take the shells, who could take the gunfire, he knew what he was doing in that sort of thing, but this was a strange world for him.”

Not everybody could handle the obscenity of state-sanctioned murder that confronted them.

Dr Michie was angry with the Germans in the camp, but there was nothing to be gained from harbouring grudges.

He realised that justice would be meted out by the Allies elsewhere, as it was to the likes of the Belsen commandant Josef Kramer, who was hanged on the gallows in December 1945 for his participation in multiple acts of genocide.

One of the most revealing parts of the interview came when Alistair asked his father how he managed to retain his sanity in such circumstances.

Dr Michie replied: “Well, we didn’t know anything about counselling at that time, so there was no counselling.

“You have so much to do, so much to think about, that you somehow disassociate yourself from it all. You have got to, otherwise you would have gone totally insane.

“But I remember a lady MP who came out in the first 10 days who was shown round Belsen, went back to Somerset, and committed suicide.

“The fellow, Richard Dimbleby from the BBC, saw Belsen in the first week and he described it very well, but I don’t think words could give you the picture.

“There were no words to describe what we experienced and saw.”

After the war, Sandy and Nora, and their daughter Sheila returned to Aberdeen in September 1946. Alistair was born in June the following year.

Dr Michie, one of four members of his family to study at Aberdeen University, accepted the post of Medical Superintendent at Woodend Hospital in the city and was given wider responsibilities when hospitals were amalgamated amid the creation of the NHS.

Eventually, this meant he was responsible for the administration of the North East of Scotland Hospital Board.

In 1974 he retired and moved with his wife to a house they had built in

Banchory.

During this part of his life, he derived much pleasure from playing golf and fishing and was also an ambitious “market gardener”, who created huge plots of vegetables and fruit of every kind in Deeside.

He was also an active Rotarian and an elder of Craigiebuckler Parish Church in Aberdeen for many years.

He might have witnessed the worst of human behaviour but it didn’t prevent him from finding the best in others.