David Spaven admits that he had picked up the trainspotting bug before he even left primary school.

As a child of the 1950s and early 1960s and somebody in a household without a car, railway trips across Scotland became a cherished part of his family existence as he travelled the length and breadth of the country.

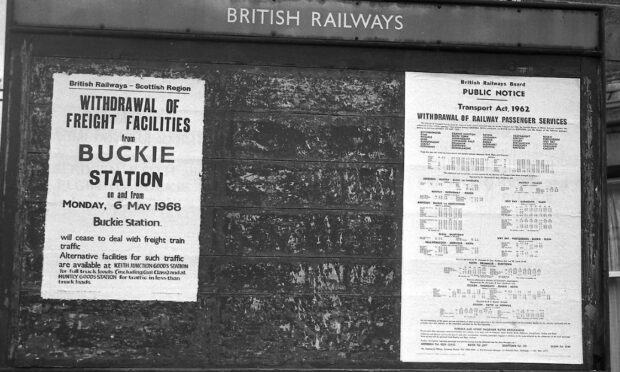

Soon enough, the sweeping closure programme, which followed Dr Beeching’s infamous report, formally titled The Reshaping of British Railways – a euphemistic way of explaining the axe was being taken to unprofitable routes – had a baleful impact on so many services in rural and remote communities.

Within a few years, passengers in myriad places across the north and north-east, who had grown accustomed to letting the train take the strain, were left without access to the vehicles on which so many of them depended.

Just a few years before the discovery of the Forties Field in the North Sea in 1970 and the subsequent explosion in the oil and gas sector, a whole swathe of the old branch lines were scrapped, many of them forever.

Even now, nearly six decades later, it seems as short-sighted as Mr Magoo.

Mr Spaven has highlighted a number of the worst-affected areas and, unsurprisingly, it includes the lack of a rail link between Aberdeen – the oil capital of Europe – and the important towns of Peterhead and Fraserburgh.

The Formartine & Buchan Railway originally opened to the Blue Toon in 1862, striking off from the Aberdeen-Inverness line at Dyce, before heading north to Ellon and Maud, where it turned abruptly eastwards.

The 16-mile “branch” from Maud to Fraserburgh started operations in 1865 and these were significant links for the next century.

Yet they were struggling to cope with increasing car usage and alternative bus services by that stage.

But did that merit them both being closed in such a peremptory fashion?

Mr Spaven said: “Less than four years after the false hopes raised by dieselisation, the front page of the Press & Journal on March 28 1963 was full of reactions to the Beeching Report, with one of the more melodramatic of the many headlines being: New Highland Clearances are Feared.

“Fraserburgh – with its trains to Aberdeen being significantly faster than the bus – had much more to lose than Peterhead with its circuitous rail route.

“Under an editorial page headline Broch Provost – Doom If…, Fraserburgh’s provost Alex Noble commented: ‘We did not expect cuts on this scale.

“We are one of the highest areas of unemployment in the country and this will mean more men out of work unless the railways in their wisdom have alternative work for the men who will be out of a job.”

Predictably, those who were involved in the bus sector in the 1960s were enthusiastic about the prospect of a substantial rise in passengers, but the news was a hammer blow to those who preferred the rail to the road.

Just three months later, a statutory British Rail public notice announced specific closure proposals for the lines to Fraserburgh, Peterhead and St Combs (and no fewer than 23 other stations served by these routes).

Public outrage was matched by prescient warnings from the Peterhead Provost, Robert Forman, who spelled out one of the most important messages about the consequences of the Beeching scythe blighting the region.

He said: “It is the easiest thing under the sun to close down the railways, but it takes a really big man to find a way of maintaining them.”

Or, as the P&J pointed out, once something has shut, it’s hard to bring it back.

Mr Spaven’s new book, Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines: Where Beeching Got It Wrong, isn’t a hatchet job on the man whose name has become notorious.

On the contrary, he has investigated a variety of different decisions which were implemented during the 1960s and concluded that Beeching has been unfairly tagged as the bogeyman of the railway bogies.

He stated: “It is not fashionable to say so but, in some ways, Beeching has had an unfair press.

“His promotion of fast inter-city services, ‘merry-go-round’ coal trains from colliery to power station and the pioneering Freightliner (container-carrying) concept took the railway in the right direction, all proving their worth in subsequent decades and continuing to do so today.”

Many places have been cut off

And yet, for all that many of the cuts made financial sense, the dismantling of giant parts of the former network created problems and hastened glitches in the network which have not been properly resolved in 2022.

As Mr Spaven added: “It was the closures – not intangible concepts, but threats to the life of places where people lived, worked or holidayed – which defined Beeching’s image in the public mind.

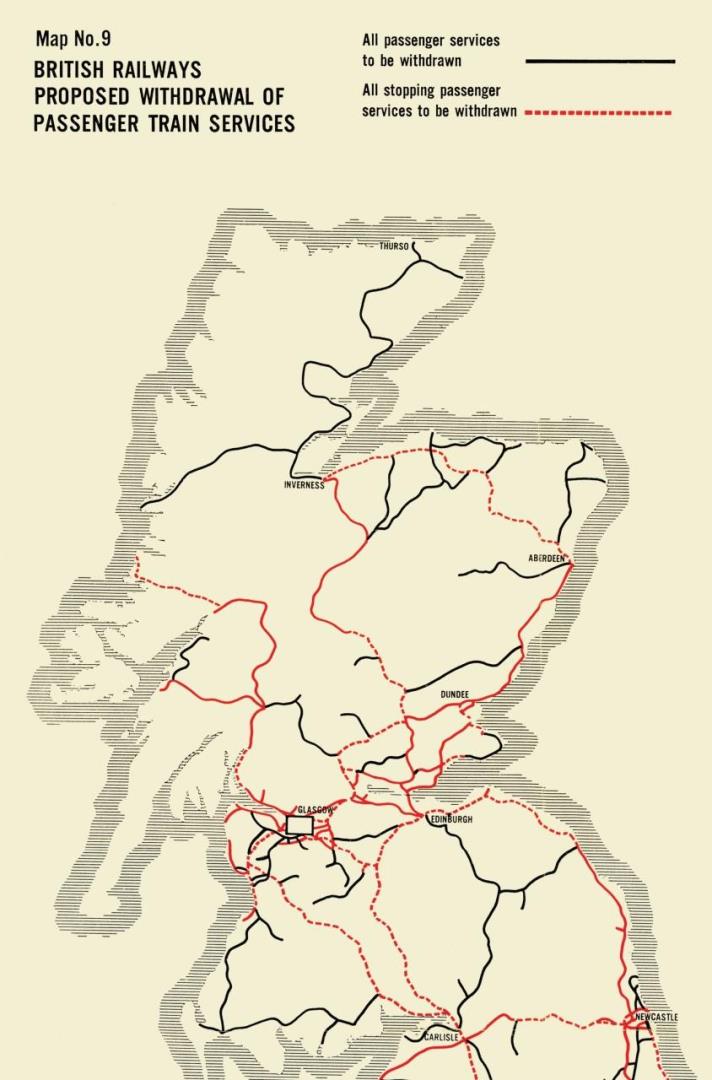

“Of the 40 or so routes slated by Beeching for passenger closure in Scotland, only nine were reprieved (including Inverness to Kyle and Inverness to Wick and Thurso).

“But main lines and/or cross-country routes disappeared in virtually every region of the country.”

These included the former Highland Main Line from Aviemore to Forres, via Grantown-on-Spey and Dava Summit; the Speyside Line, the Moray “Coast Line” and the Keith-Dufftown-Elgin “Glen Line” in the north east; and the prestigious double-track Strathmore Route, where Glasgow-Aberdeen expresses traversed the fastest stretch of railway anywhere in Scotland.

And nowhere has been more badly affected than the north east.

There is still debate around building new rail links between such places as Peterhead and Fraserburgh and Aberdeen, but even before the Covid pandemic, some experts in the transport industry maintained that the finance required to bring any such schemes to fruition would easily surpass the cost of the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route at £745m.

In which light, there seems little possibility of it moving from talk to action and not in a period of rising inflation and budget-tightening.

However, Mr Spaven’s analysis – and he has spent his working life in and around the rail industry – has unearthed strong evidence of a “stitch-up” and exposed how the Beeching Report ignored the scope for sensible economies which would have allowed many of the axed routes to survive and prosper.

And he has even explored a potential renaissance of branch lines, propelled by concerns over road congestion and the climate emergency.

Why not? After all, he has evoked the words of the late, great John Betjeman, who once wrote: “If you want to see and feel the country, travel by train.”

For many people, that’s still as true today as it was 80 years ago – 0r at least when the network is running properly!

- Scotland’s Lost Branch Lines is published by Birlinn at birlinn.co.uk