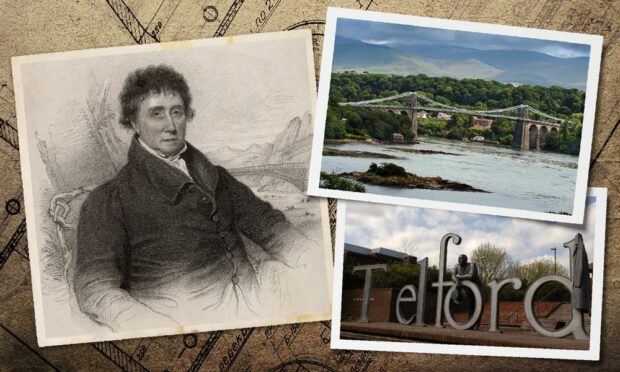

He was one of the great Victorian engineers of the industrial revolution.

Much of the infrastructure of the Highlands we take for granted today is thanks to the work of this pre-eminent Scottish civil engineer.

Thomas Telford’s work is of such national importance that he is buried in Westminster Abbey- but what was he like? Who was he? We don’t give him much thought these days.

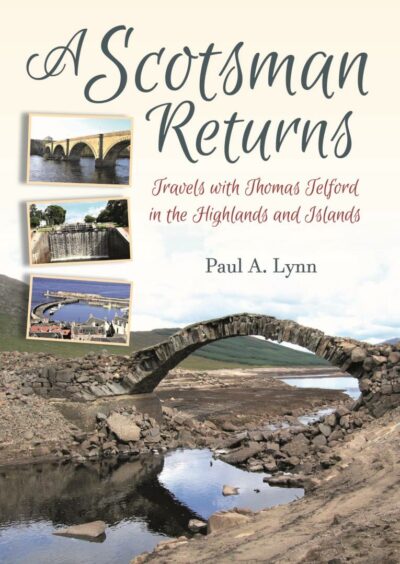

A new book by chartered engineer and author Paul A Lynn shines a new light on Thomas Telford the man, rather than the workaholic engineer who died still in the harness aged 77.

A Scotsman Returns, Travels with Thomas Telford in the Highlands and Islands reveals Telford as a kindly, compassionate individual with a sense of fun and wonder, and happy nature which never left him.

In Britain, you’re never far from a Telford construction.

Telford spent 2o years in England and Wales designing and building canals, bridges, aqueducts, roads, harbour improvements and churches.

Most of his Scottish work is in the Highlands and his influence here is enormous and unmistakable.

The Caledonian Canal is one of his major achievements.

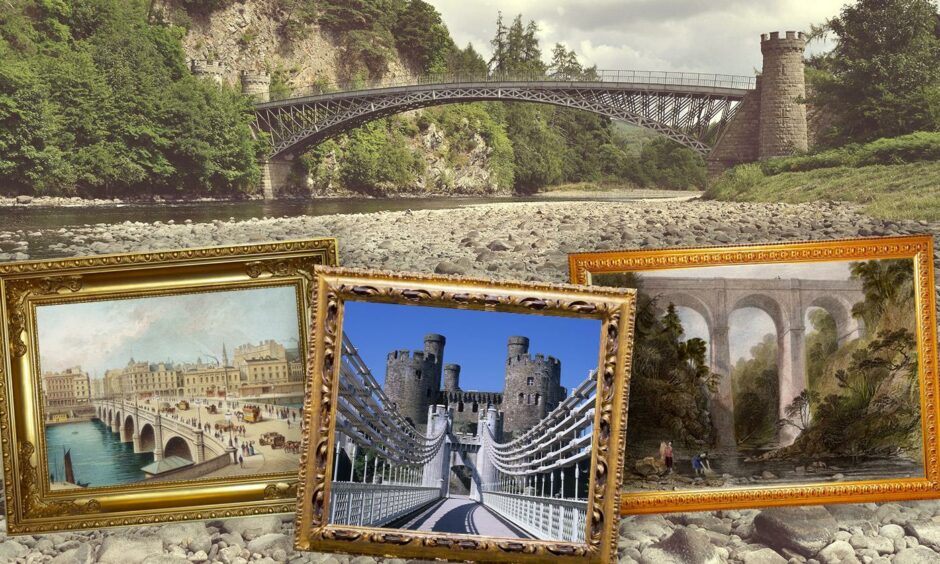

Then there are the bridges and aqueducts, such as Glen Loy aqueduct, Helmsdale Bridge, Bonar Bridge, the Telford Bridge at Invermoriston, Craigellachie Bridge, Sligachan Old Bridge to name but a few.

Not to mention the 32 Parliamentary Churches, many harbours, jetties and roads.

Rattling these off barely touches the surface of the achievements of a man born in a lowly shepherd’s hut in Eskdale, Dumfries and Galloway.

Poverty

Telford grew up in great poverty, yet how he beat his humble beginnings to become a man with a towns and colleges named after him is testament not only to his talents, but also to his amiable personality.

Telford and his mother Janet, widowed only months after he was born, confronted their abject poverty with hard graft and cheerfulness.

So much so that Thomas was known as Laughing Tam, a popular figure wherever he went.

He stayed with neighbours, who also gave his mother employment when they could, milking sheep, hay-making, harvest shearing, ‘contriving not only to live but to be cheerful’.

Full of fun, young Tam herded sheep and ran errands in exchange for food, clothes and clogs.

He thirsted for education and with the help of relatives, he was able to attend Westerkirk parish school.

Self-educated

He continued to educate himself for the rest of his days, insatiably reading and learning about all the latest innovations and advances in science.

Nevertheless, it’s a big leap to rise to pre-eminence from such humble beginnings.

Telford and his particular set of skills came into the world at the right time.

The first career move Thomas made was going to Langholm as an apprentice stonemason.

The village was little more than a collection of mud hovels at the time, but landowner the Duke of Buccleuch was about to embark on a programme of improvements.

There the young Thomas worked on paving tracks, bridging fords, building stone houses and even hewing gravestones and ornamental doorways.

To this day you can see his own mason’s mark on stones below the western arch of Langholm Bridge at low water.

He went from there to Edinburgh in 1780 as the New Town was being built, but Auld Reekie’s grandeur couldn’t hold him for long.

Heads for London

He set off for London 18 months later armed only with his mallet, chisels and leather apron.

Through Langholm connections he obtained an introduction to Sir William Chambers, architect of the grandest construction project of the time, Somerset House, where he was employed as a first class mason.

Thus began his trajectory towards becoming one of the most respected civil engineers of his age.

Paul Lynn relates that he continued his self-education with dedication, going a bit chemistry-mad at this point.

He went to the theatre and took a shine to a famous actress known as Mrs Jordan — but she was spoken for, by among others William IV by whom she had ten children.

He attended concerts, but discovered that he didn’t really enjoy music.

Mr Lynn thinks he may have been tone-deaf.

Telford became a man of the world, powdering his hair, and putting on a clean shirt three times a week.

He also continued to write faithfully to his mother, in capital letters that she could easily read by her fireside.

He penned poetry, mainly privately, as a form of relaxation, though one of his works, a poem about his home village of Eskdale, was published.

This love of verse brought him into contact with the poet Robert Southey, whom he met for the first time in Edinburgh in 1819 to embark together on a journey the length and breadth of Scotland.

Like kindred spirits, the two clicked immediately.

By this time Telford was 62 and engaged in dozens of Highland infrastructure projects, not the least of which was the Caledonian Canal.

Southey was 45, and the reigning poet laureate.

His privileged background—Westminster School, Balliol College Oxford—couldn’t have been more different from Telford’s.

It was a good thing they got on so well, for during their six week journey, the pair often had to share a room.

Southey was bothered by a ‘volcano’ on his head, a suppurating tumour which had frequently to be cleaned and dressed— Telford even proved equal to doing this for his new friend.

Southey kept a journal of the tour, and records his first impressions of Telford.

“There is so much intelligence in his countenance, so much frankness, kindness and hilarity about him, flowing from the never-failing well-spring of a happy nature, that I was upon cordial terms with him in five minutes.”

In a horse-drawn landau and accompanied by another family, their route took them to Sitrling and the Trossachs, Perth, Dundee, Montrose to Aberdeen, then west to Banff, Elgin and Grantown-on-Spey.

Thence along the Moray coast to Forres, Nairn and Inverness.

Venturing on, they took in Dingwall, Bonar Bridge and Dornoch before heading down the Great Glen to Fort William, Glencoe and Inverary, finishing in Glasgow.

They visited many of Telford’s works along the way leaving Southey in ever-increasing awe of the great engineer.

Six weeks touring in close proximity under sometimes trying circumstances failed to break the bond of friendship between Telford and Southey, who wrote of his melancholy at their parting: “A man more heartily to be liked, more worthy to be esteemed and admired, I have never fallen in with.”

It was Southey who coined the nickname ‘Colossus of Roads’ for the friend who made improvements to more than 1,000 miles of roads, many of them in the Highlands.

Mr Lynn said: “One of the main aims of my book is to present Telford as a man of the Scottish Enlightenment, whose engineering had profound social consequences.

” For example his harbour works were crucial to the fishing industry.

“His bridge design at Craigellachie was a wonderful blend of science and art.

“He was also a man of compassion and kindness who made many friends.”