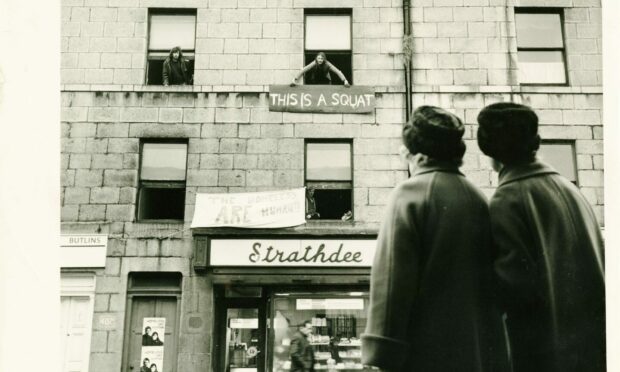

It was a protest in Aberdeen that spoke to the anger many people had about the state of housing in the city 50 years ago.

A banner was hung outside a window in George Street in 1973 bearing the words “This is a Squat” as illegal occupiers complained about the lack of new houses and the plight of the homeless in the north east’s biggest community.

In common with many other parts of Britain, devastated by the Second World War, there were large areas of slum tenements which were no longer habitable, while the wreckage caused by concerted German bombing raids on Aberdeen had left many cavernous craters to be rebuilt from scratch.

A large construction programme was carried out in the late 1940s and 1950s but, even so, problems remained in providing new homes for those who required them – and one of the controversial solutions to the issue was the creation of brutalist high-rises which remain a part of the landscape.

Most of those who left the dilapidated tenements were glad to be offered the chance of enhanced accommodation – they had lived long enough in the cramped, confined, insanitary dwellings described in Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s novel, Grey Granite, to relish a new beginning not far from their roots – but many harboured reservations over moving to the sprawling concrete jungle.

And, six decades later, housing is still a vexed question for Aberdonians who can’t afford expensive mortgages or access to affordable properties.

Tenement life was hard, but often brought people closer.

One account of the situation in Aberdeen from the 1930s pinpointed signs of endemic poverty and mothers – whose husbands were frequently away at sea for long periods – being forced to make precious little basic food supplies go a very long way.

And yet, whether in examining Grassic Gibbon, or reading accounts of visitors to the city, such as Margaret Learmonth from Sydney in 1934, there were communal qualities which meant neighbours looked out for each other and did whatever they could to assist those who needed it.

Miss Learmonth, who was employed as a nurse in the city, wrote in the Aberdeen Journal: “I was worried about the spread of sickness and disease when I first went into the tenements because so many people were living in such close proximity that, if somebody fell ill, others must surely follow.

“However, the women who were in charge of the households worked tirelessly to keep their homes clean and their children warm.

“Milk and bread were precious commodities, but these women shared what they had with others.

“There seemed to be a common attitude that everybody had to pull together.”

In the aftermath of the war, there was a general realisation that a major housebuilding programme was urgently required in the Granite City.

Yet given the dearth of basic resources available to construction companies, arguments continued about the best way of bringing it to fruition.

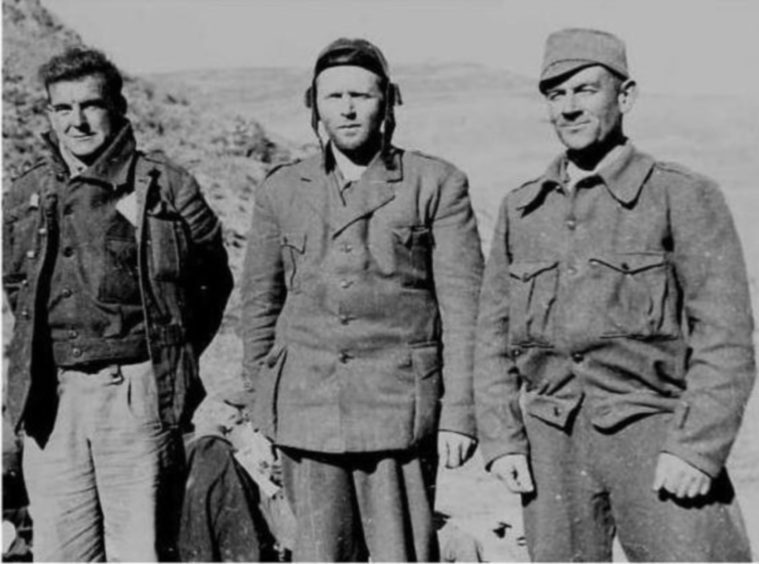

Prior to the 1950 general election in Britain, the scale of the malaise was debated by the various candidates, including the Communist Party’s Bob Cooney, who had previously fought in the Spanish Civil War.

He pointed at many of the tenements and stated: “Are these the homes fit for heroes which the politicians promised in 1945? Or are they another sign that the promises weren’t worth the paper they were printed on?”

The Aberdeen Journal reported at that time: “The gloves are off for a hard-hitting finish to the (election) campaign in North Aberdeen.

“National interest may have switched to momentous issues like peace talks with Stalin and the H-Bomb, but here, local matters are holding their place.

“Nowhere, for instance, is the housing issue being raised more sharply than in this constituency, where the majority of Aberdeen’s industrial workers live.

“The city’s waiting list for homes – estimated at anything from 15,000 to 18,000 – is an ever-recurring point. And, on this subject, Mr Hector Hughes (Labour), who is defending his seat in a four-cornered contest, finds himself being assailed from both the Left and the Right.”

As the piece added: “Mr Robert Cooney proclaims himself in his election address as the ‘only candidate the Tories really fear’.

“On another page, he joins with the Conservatives in flaying the socialists for their housing record, declaring that the present rate of building is enough to house only one out of every three newly-married couples.

“This, he says, is leading to a crisis which has yet to be addressed.”

Were high-rises pie in the sky?

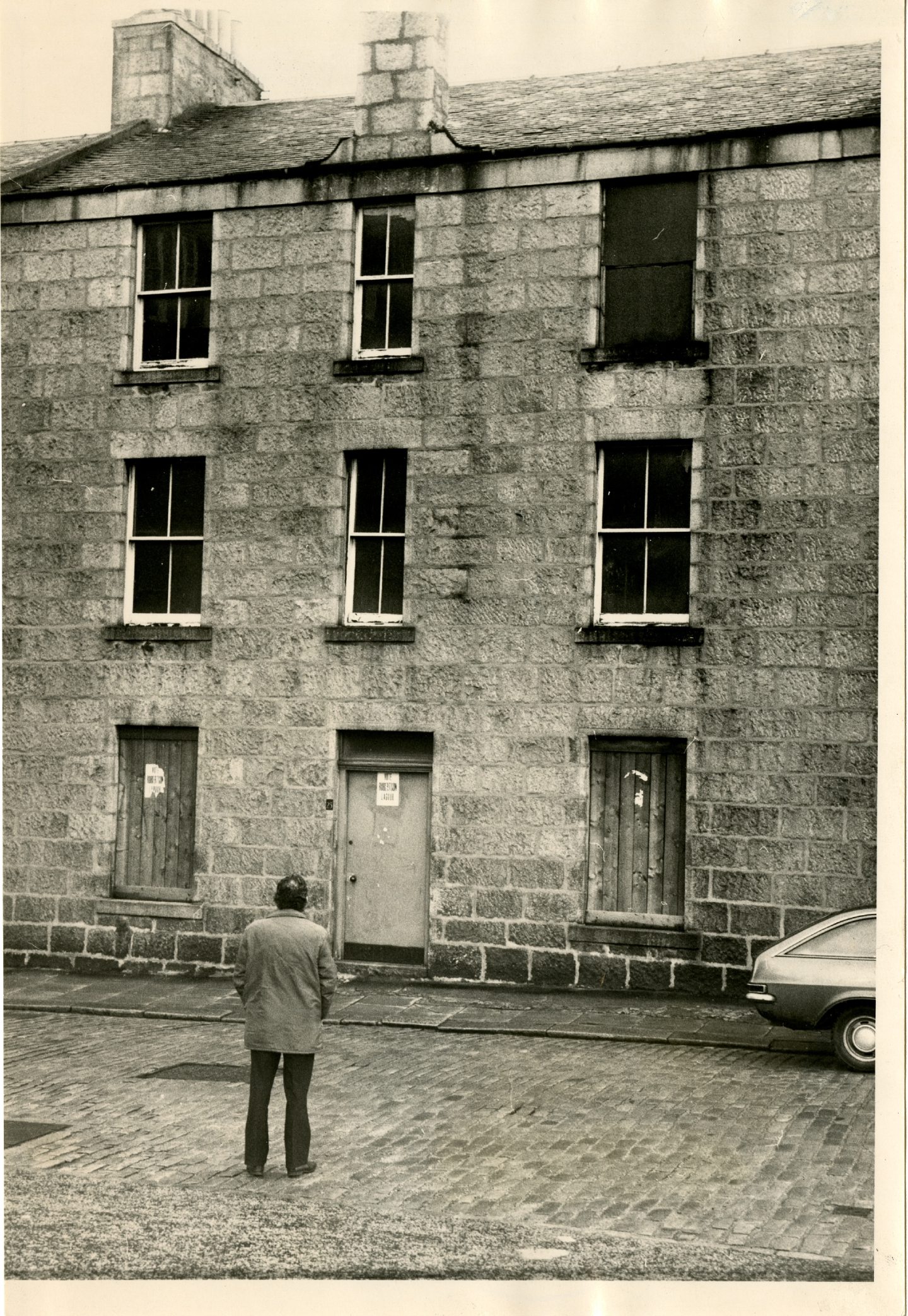

In many instances, politicians from across the divide acknowledged that the tenements’ day was done.

But the subsequent proposals to construct a high-rise “road to the sky” was not universally admired.

It was initially billed as a proper pathway to future prosperity for families and their children in new communal flats with indoor toilets and heating.

But, right from the outset, the plans had their detractors, who wondered why modern-style tenements couldn’t be erected as an alternative to flats.

John Corral, a former city councillor, can still recall his feelings when the authorities decided that the old dilapidated tenements should be flattened.

It was promoted as the launch pad for innovation and improvement yet he believes many mistakes were made as the city was transformed.

He said: “Houses were single glazed and my first flat, in Walker Road, had a shared lavatory on the stairs and a cast-iron sink with only cold water inside.

“Bearing in mind the hardships that people had suffered, the prospect of demolishing extensive slum areas and moving into self-contained, roomy flats was eagerly awaited.

“Gone, however, also went the closeness and the social interaction that living in these old street buildings offered.”

And, when many of the tenements were replaced with high-rises, initial optimism soon gave way to disappointment for many of the residents.

In 1950 Baillie Frank McGee, the city’s housing convenor, announced he was determined to eradicate the “appalling slums” which still existed.

You saw places being boarded up and the caretakers weren’t around any more to deal with the troublemakers.”

It was the catalyst for a major new venture which, in 1952, led to the local authority approving Aberdeen’s first ‘multi’ building – a nine-storey block in Ashgrove Road which opened in 1961 – and proved the template for the subsequent creation of many high-rise structures in the adjoining areas.

Graham Sherriffs was among the residents whose initial positivity about the high rises was gradually replaced by a sinking feeling.

He said: “We loved living at Seamount Court and our two children were brought up in what was a great community spirit and good mix of age groups.

“There was a real sense of pride from the residents with communal cleaning being done on a regular basis and both Seamount and Porthill had caretakers, which helped a lot.

“The surrounding areas were also much better maintained but, sadly, by the time we moved across the road, an influx of undesirable tenants had started to move in.

“I believe that bad choices by the council allowed this to happen and, around the same time, the introduction of contract cleaners and dismissal of resident caretakers contributed to the falling standards.”

Reality was sinking in for those in the giant tower blocks: this was no brave new world, but a short-lived escape into a noisy, intrusive environment, where you were at the mercy of who was living upstairs or next door.

It seems remarkable that a bitter battle has been waged in 2021 and 2022 between Aberdeen City Council and Historic Environment Scotland over the latter’s decision to give listed-building status to eight of the relics from the ’60s: those at Gilcomstoun Land, Porthill Court, Seamount Court, Virginia Court, Marischal Court, Thistle Court, Hutcheon Court, and Greig Court.

A little Aberdeen sunshine for you…recording the inner-city multis back in July 2019. Now category A listed.https://t.co/O04IljY1ox pic.twitter.com/W4XqjgtxTT

— Dawn McDowell (@DawnieMcD12) February 19, 2021

Last month, in response to criticism from the local authority, the Scottish Government’s planning and environmental appeals division ruled that the last three of these buildings should not be included in the listing.

But just as the old tenements served their purpose, so have these flats – or, at least, that’s the belief of some who formerly lived in them.

Ian Young and his wife, Marilyn, moved into Hutcheon Court in the mid-1970s and shared Mr Sherriffs’ opinion of their initial positive aspects.

He said: “We moved up to the city from the central belt to study and didn’t have a lot of money, so we were thrilled when we ended up in the high rise.

“We kept in touch with the older members in the building and there was a really upbeat atmosphere.

“It wasn’t like The Waltons – one or two of the lads liked a drink and you’d sometimes hear them singing at the top of their voices.

“But we got our hands dirty to do some cleaning and a few of the younger folk bought the messages for the senior citizens when the weather was bad.

“Eventually, though, things changed for the worse.

“A lot of people were unemployed in the 1980s and things got so bad that people ended up just bailing out with their stuff and leaving their homes empty.

“Then you saw places being boarded up and the caretakers weren’t around any more to deal with the troublemakers.

Time for a new strategy in Aberdeen

“I’m still glad we stayed there (for eight years) but things had definitely deteriorated and I can’t understand this listed buildings news.

“The high rises were good for us in the 1960s and the 1970s but it’s surely time new houses were built to replace them.”

That’s a debate that is already under way in Aberdeen.