We’ve all heard about the introduction of prohibition in the United States and the subsequent launch of bootleg liquor suppliers, illegal speakeasies and a thriving trade in hooch and moonshine.

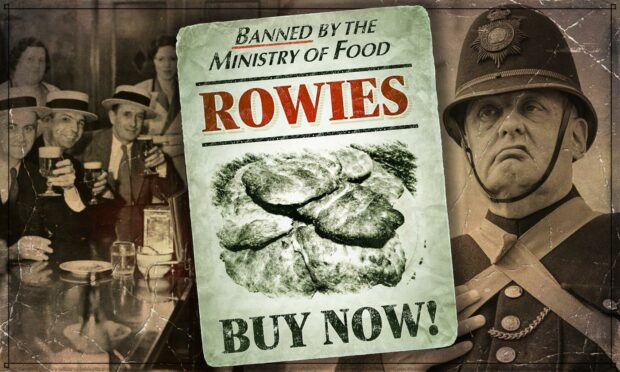

But did you know that Aberdeen experienced its own black market in rowies – or butteries – when they were banned by the Ministry of Food in 1917?

Even as the First World War continued in the trenches, and families in the north-east anxiously awaited news of their loved ones on the Western Front and other scenes of conflict, there was acrimony of a different nature at home, as government inspectors drew up strict regulations on what could and couldn’t be served to customers on their shopping trips.

The newly-baked rowie, beloved by so many people in the Granite City and from Fraserburgh to Forvie and Peterhead to Peterculter, was among the myriad items which faced the axe for nearly two years from 1917 to 1919.

But that didn’t stop a few retailers from maintaining the supply chain – with some of the culprits landing in the dock in the process.

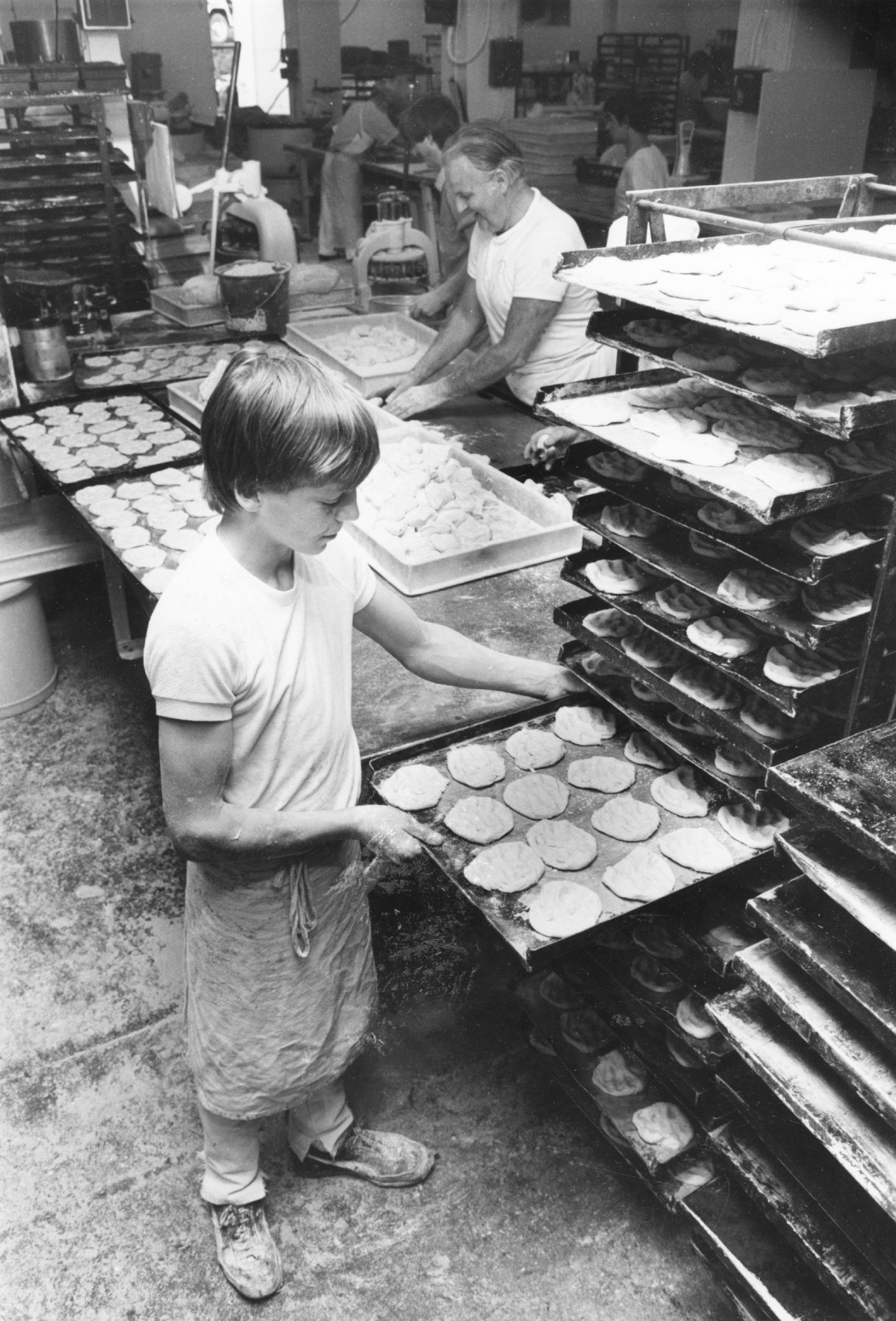

Rowies were originally made for fisherman who needed food that would keep for a fortnight.

This also explains why they are so easily shipped worldwide.

But they are also delicious straight from the baker’s oven and thousands of north-east folk have purchased their supply every morning of the year for as long as anybody can remember.

However, none of that cut any ice with the Ministry of Food, which issued decrees about everything from bread to sugar and herrings to haddock, as Britain suffered increasing food shortages during the global hostilities.

The Press & Journal carried regular news on which foodstuffs were being rationed, banned or put under the microscope by the authorities.

Then, on August 27 1917, came the tidings which many had dreaded.

Delicacy faced the bread bin

Under the headline, “Threat to Aberdeen’s Morning Delicacy”, the paper spelled out why the rowie was being proscribed.

It said: “When the war came and with it a series of regulations and explanations by the Food Controller as to what might and might not be made by the baker, Aberdeen’s morning roll, known locally as the ‘buttery rowie’, was allowed to be baked hot and sold straight from the oven.

“One of its chief ingredients is indicated by its name and it is really more of a plain bun than the bap or morning roll to be had in the south (of Scotland).

“The Aberdeen breakfast speciality was sent to the Food Controller with a representation that it did not come within the category of bread which must not be sold within less than twelve hours of it being baked.

“But now, after a lapse of several months, the bakers have been informed that the buttery roll is to be banned. Its manufacture is an important brand of trade locally, particularly in working-class districts, where breakfast consists of porridge and milk, followed by a cup of tea and a buttery.

“Employers and employees are thus likely to be badly hit by the prohibition and are set to take action to communicate to the Food Controller that such rolls, forming so important a part of the food of the working classes in industrial centres (and fishing communities) should be permitted.”

It might have been a small thing in the midst of the Great War, but sometimes, maintaining morale involves more than singing patriotic songs.

This sparked substantial consternation in the north east and the Aberdeen Trades and Labour Council swiftly approached the local Food Control Committee to mount a defence of their cherished items.

Officials complained that the war committee had no representatives from the working class – the very people who relied on the rowie for sustenance through their daily grind, as well as the bakers who produced them – and vociferously claimed that people in Aberdeen were tired of profiteers.

One report said: “It was argued that while Edinburgh and Glasgow bread rolls had been stopped because of the war, the Aberdeen roll was of a very different order, its high lard content making it more akin to ham and eggs than the bread roll that was made everywhere else, meaning it was breakfast for many poorer people in Aberdeen.

“However, the Ministry of Food declared that no bread could be sold which contained butter, margarine or any sort of fat so the fresh Aberdeen rowie’s days were numbered”.

And the party was over – or for the majority, at least.

However, some bakers responded with a V-sign to the edict and decided they would keep producing rowies for their regulars and damn the consequences.

Given the hours they toiled, starting in the wee small hours of the morning, they reckoned they could defy the draconian diktat if they were smart.

Doubtless, some of these bootleg buttery merchants were never rumbled and carried on regardless, selling their wares to customers.

But there were others who ended up in court and faced serious penalties.

They had to shell out a lot of dough

On July 1 1919 the Press & Journal carried details of the fate of two Aberdeen retailers whose illicit buttery production had landed them in hot water.

Under the headline: “Fined for selling new buttery rowies”, the paper reported on how the authorities had clamped down on these devilish miscreants.

Curiously enough, if they had let their goods lie in the back of the shop for a couple of days, they wouldn’t have faced any punishment.

But rules were rules and the judiciary was determined to make an example of them.

The item said: “Two cases of interest to bakers throughout Scotland were heard at Aberdeen Sheriff Court yesterday before Hon Sheriff-Substitute Mackinnon. They related to the sale of new morning buttery rolls.

“The first case was that of Peter Main, of Aberdeen, who pleaded guilty to having, on two occasions, sold halfpenny butteries, which were not made at least 12 hours previously.

“Mr T McLennan, procurator-fiscal, stated that the accused had been selling the new rolls for more than two months, because he was unable to sell old ones. It was not fair for one or two others to take advantage over others.

“Matthew Mitchell of Summerhill Farm, Aberdeen, admitted having sold four halfpenny buttery rolls in his shop in George Street and also admitted a previous conviction for a similar offence.

“The Sheriff, in imposing a fine of 20s (£1 on both men), said the baking trade must realise that, while these orders were in force, they must be obeyed.”

The monetary penalties may sound modest in today’s terms. But they amounted to the price of 480 rowies – which is a lot of dough for any baker.

Finally there was a reprieve

In 1919 an appeal was sent by officials in Aberdeen to the Ministry of Food, requesting permission to produce buttery rowies again.

At first, their request was denied and the controversy continued for months, leaving many bakers and customers angry and baffled as to the reasons behind the stalemate.

One P&J letter writer asked in May: “Our soldiers fought bravely in the war, while workers kept the home fires burning. They surely deserve to be given some decent provisions and have their buttery rowies back.”

And finally, in August, and to much delight across the region, the unpopular order was revoked and hot buttery rowies were on the menu again.

Yet that didn’t stop another battle being waged: the conflict between those who insist a rowie should be called a rowie and emphatically not a buttery.

Now, there’s one battle that might never see a ceasefire!

You might also like:

Dare you read the new story about the ghost in Aberdeen pub Ma Cameron’s?

Toasting the greats: A look at classic Aberdeen pubs both past and present