It’s one of the great feats in exploration history; the survival of Ernest Shackleton and his crew members on the Endurance after they were trapped in pack ice in the Antarctic more than 100 years ago.

After setting off in August 1914, just a few days before the outbreak of the First World War, these men weaved a treacherous path through the Weddell Sea and were within just 85 miles of their destination when they found themselves trapped in the midst of a frozen white nightmare.

Soon enough, Shackleton and his comrades were stranded in desperate straits.

They subsequently spent 20 months there, and were engaged in two near-fatal attempts to escape by open boat, before being rescued.

Yet while the captain’s name has been preserved for posterity, Alexander Macklin, one of the ship’s surgeons on the voyage, surely deserves greater recognition, not only for the qualities he demonstrated throughout his privations in the frozen south, but his courage and resilience with the medical corps in France, Italy and Russia during his service in the Great War.

Macklin, an adopted Aberdonian, was given the Military Cross for tending wounded soldiers under fire.

A celebration of this remarkable character and his links to the Granite City in war and peace is overdue.

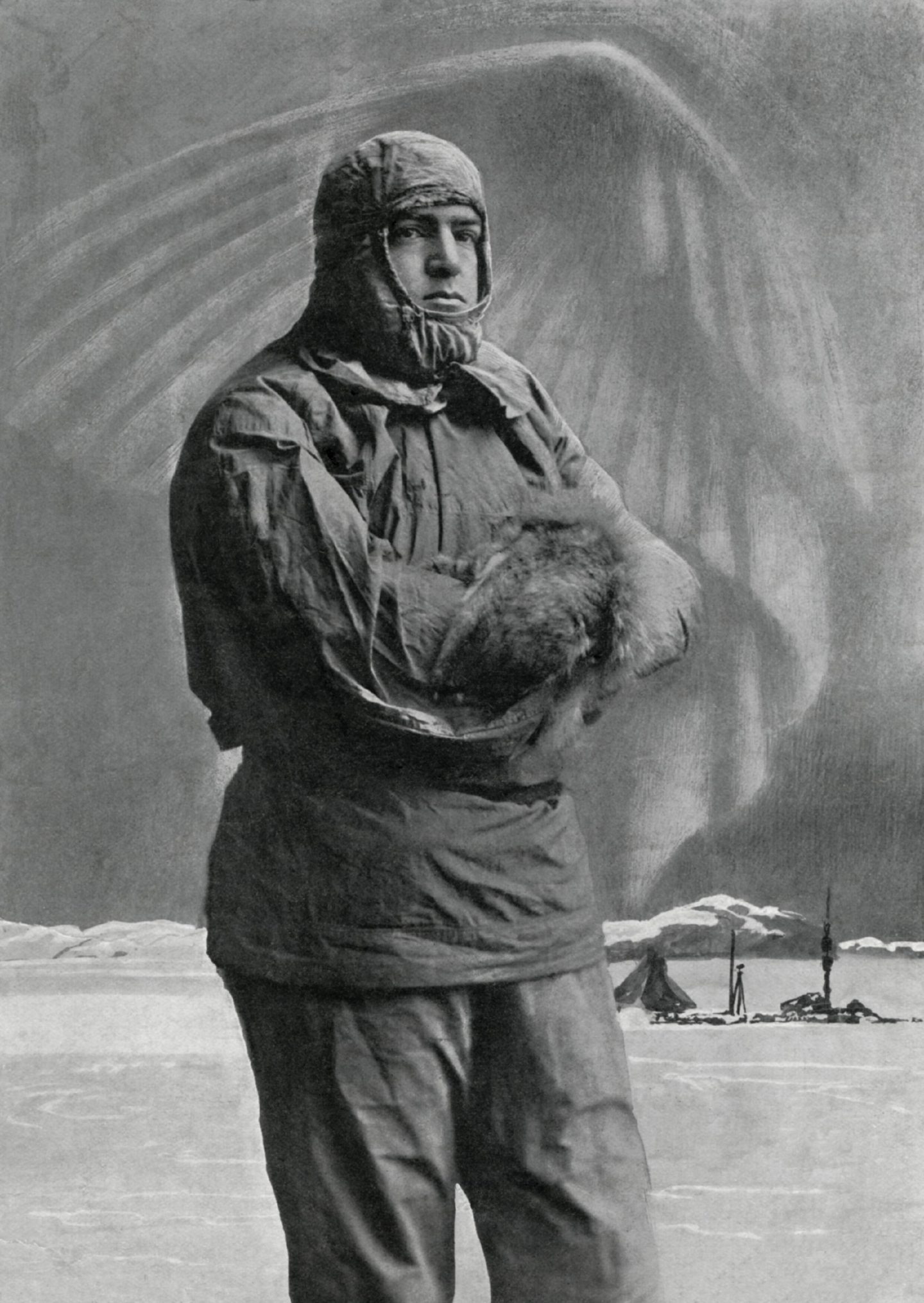

When Shackleton embarked on his Imperial Trans-Antarctic expedition at the age of 40, he was already widely regarded as a national hero, although his life was a story of close shaves and what-might-have-beens.

When he was selecting the crew to carry out the mission, he was fully aware of the fate suffered by his former colleague, Robert Falcon Scott, who had perished along with several of his companions two years earlier in their ill-fated bid to reach the South Pole ahead of Norwegian Roald Amundsen.

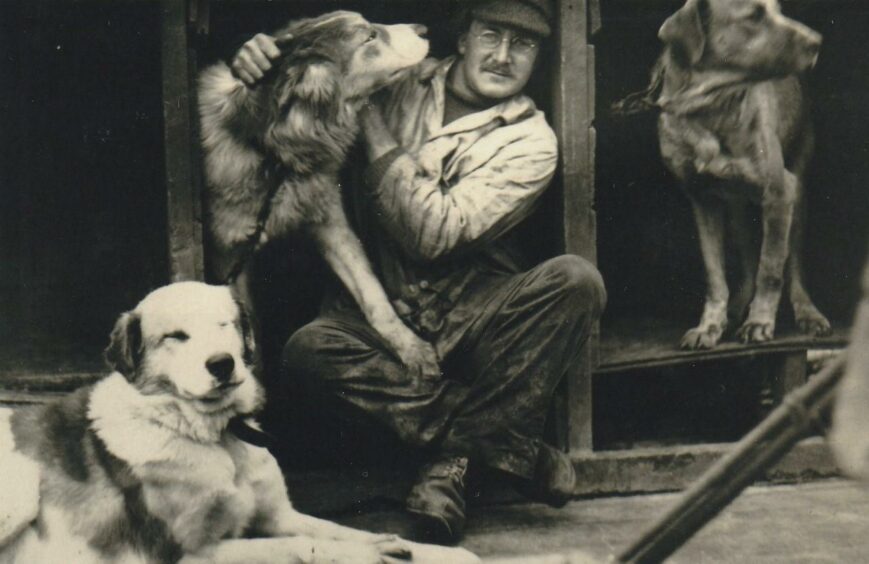

But he was a canny judge of character and soon forged a close bond with Macklin, who was prepared to participate with his medical duties as well as scrubbing the decks and looking after the dogs on Endurance.

The crew were given a rapturous ovation as they left Britain, but the outbreak of war overshadowed much of their later travails.

For the first few months, they negotiated their way through often treacherous conditions and, after battling resolutely past a daunting 1,000 miles of pack ice in the first six weeks of 1915, it seemed they would succeed in their objective.

However, the closer they advanced, the harder it became and, on February 24, Shackleton ordered the cessation of the ship’s route and his vessel officially became a “winter station”; something that frustrated all the men on board.

‘He showed sparks of real greatness’

Macklin wrote in his diary: “It was more than tantalising, it was maddening because we knew we were within a single day’s journey to the landing base.

“Shackleton, at this time, showed one of his sparks of real greatness. He did not rage at all, or show outwardly the slightest sign of disappointment.

“He told us, simply and calmly, that we must winter in the Pack; explained its dangers and possibilities; never lost his optimism and prepared for winter.”

In the following weeks, Shackleton worked tirelessly to prevent his men from cabin fever or slipping into despair.

There were sing-songs, seal-scouting trips, exploratory hikes and lantern slide lectures – and even an impromptu football match – but on Mayday, the sun disappeared entirely and was not seen again for the next four months.

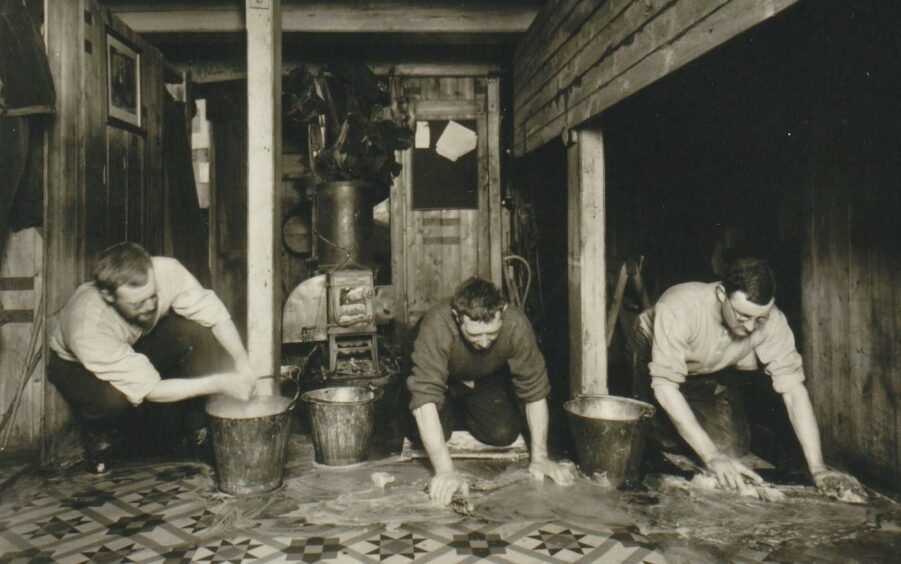

They were isolated from everything and two of the Scots, Macklin and Robert Clark – another Aberdonian, who later played cricket for Scotland and was an excellent footballer – volunteered for what were regarded as disagreeable jobs.

The zoologist, Clark, shovelled coal, worked on the dredging nets and continued with his scientific duties, which included skinning penguins.

Macklin, meanwhile, was kept occupied with the dogs and was appointed as a sledging team driver, which suited his relish for fresh challenges.

However, as time passed and the horror of their situation became all too clear, tensions mounted.

There was the constant risk of catastrophe, the fear that the men would succumb to the chill environment that imprisoned them.

As 1915 turned into 1916, they were stuck on the precipice, the group separated into two parties and Macklin was one of those marooned on Elephant Island, at the mercy of the blizzards which enveloped them.

He wrote: “Everything was deeply snowed over, our footwear was frozen so stiff that we could only put it on by degrees, and there was not a dry or warm pair of gloves amongst us.

“I think I spent this morning the most unhappy hour of my life – all attempts (at escape) seemed hopeless and Fate seemed determined to thwart us.

“Men sat and cursed, not loudly, but with an intenseness that showed their hatred of this island on which we had sought shelter.”

Yet, if the party was being tested to the limits of their capability, they never surrendered or succumbed to misery – and Macklin, a tough-as-teak individual, was among those whose courage in adversity still shines in his log.

The Endurance was eventually destroyed by the packed ice and the crew were left to survive on their wits and with Shackleton striving to maintain morale.

But they never buckled and Macklin was one of the key individuals in maintaining the belief they would find a means of escaping from their plight.

His part in the expedition has been highlighted by Aberdeen history enthusiast Bill Halliday, who is convinced that any “Hall of Heroes” created in the city should recognise the achievements of this formidable figure.

And he has made a compelling case.

He said: “Whilst Shackleton rightly deserves the credit for the leadership which he demonstrated in bringing all the members of the party safely back home, following the loss of the ship to ice, in a harrowing tale of hardship and outstanding feats of seamanship and mountaineering, he was the first to acknowledge the vital part played by Alexander Macklin OBE.

“We can be sure that, without his care, some of the party would not have survived the rigours of the extreme conditions faced after the loss of their ‘home’ and the months of suffering they endured on Elephant Island supported by the most basic shelter and diet.

“He was seen stripped to the waist in freezing conditions as he carried out life-saving surgery and he almost ended his stay there in a similar condition as he raced to the look-out spot to tie his much-repaired jacket to the rudimentary flagpole in order to alert the rescuing ship.

“His arrival back from one severe challenge was immediately followed by another as he volunteered to serve in the medical corps in the First World War, which took him to France, Italy and the Eastern front in Russia where again he was to face frozen conditions (and tanks) which he described as “tame” compared to Antarctica.

“At the conclusion of hostilities, he continued to provide his surgical skills, (initially by setting up a practice in Dundee in 1926 and serving in the medical corps in the Second World War) and, for many years, worked at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, even continuing in a volunteering capacity after his retirement. (He died in 1967, aged 78).

“It is a source of extreme jealousy on my part that my sister, June, had the benefit of working with Dr Macklin at the hospital, where she described him as most unassuming and caring and a true gentleman, whereas I have had to rely on books to learn of his qualities and inspiring life.”

There was a poignant conclusion to their relationship when Shackleton invited Macklin to join him on an expedition in 1922 on board the Quest.

The ship was plagued by engine trouble and diverted to Rio de Janeiro before repairs were carried out and it travelled onwards to South Georgia.

But Shackleton was ailing badly by this stage and author Caroline Alexander wrote about his demise: “Macklin sat with him quietly for some minutes and took the opportunity to suggest that he might take things easy in the future.

He carried out the great man’s autopsy

“The Boss replied: ‘You are always wanting me to give up something. What do you want me to give up now?’

“These were Shackleton’s last words. A massive heart attack took him suddenly and he died at 2.50am.”

It was a massive shock but Macklin was as unflappable in these sad circumstances as he had been on Elephant Island and carried out the autopsy on his fabled commander, traveller – and friend.

One journey had ended, but this redoubtable Scot still had much more to do.

More like this:

From Trafalgar to the Terror via Stonehaven: Family finally have doomed hero’s Arctic medal

Aberdeen charity stalwart reveals her family’s links to TV drama The Terror