Renowned Scottish historian Jim Hunter has never forgotten how close the world came to nuclear annihilation in the 1960s.

On a morning in October 1962, when the Cuban missile crisis came to a head, the youngster was up as usual at around 6.30am to have a quick breakfast, cycle the mile or so to Duror Station and catch the early-morning train to Oban – where he was a second-year student in the town’s high school.

The news was full of speculation about whether nuclear weapons might be deployed by the Cold War combatants if discussions broke down between US president John F Kennedy and his Russian counterpart, Nikita Khrushkev.

This was at a stage when the world stood on the precipice – and Mr Hunter, now the emeritus professor of history at the University of Highlands and Islands, was among those who sat in class and worried about their future.

Nuclear war was a very real prospect

He said: “There was no TV reception of any kind in Duror. But breakfast coincided with the seven o’clock news bulletin on BBC Radio’s Home Service.

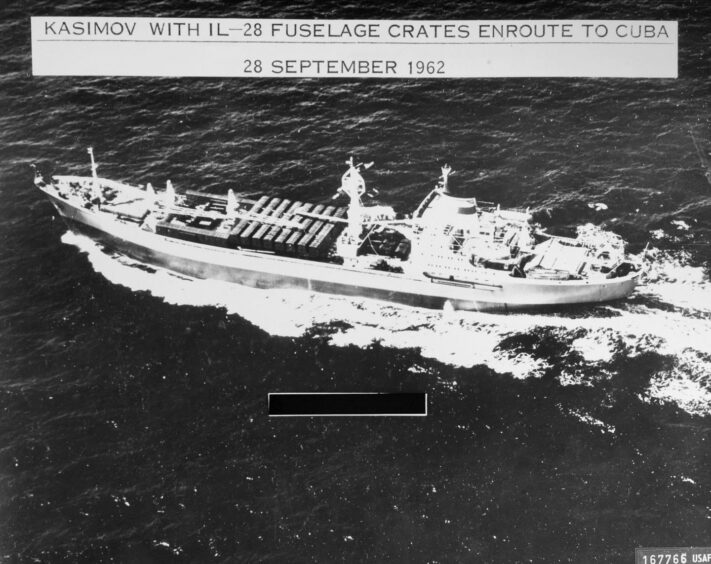

“A Soviet Russian convoy, it appeared, was steaming towards Cuba where, if its ships challenged the American naval blockade, which President Kennedy had put in place around the island, would be treated by the US as an act of war – a war, it seemed likely, that could escalate into a nuclear exchange.

“While on our way to Oban, at breaktime and at lunchtime, my pals and I must have talked about what might be about to happen.

“I have no recollection of that but what I remember with a clarity that has not faded over time is attending that afternoon a music class held on the top floor of what was then the newest part of the Oban High School complex.

‘I gazed out at the Holy Loch’

“Music was not my strongest subject. That helps to account for the minute or two or three or four when, having lost all sense of what our teacher was saying, I gazed through the classroom window at the hills to the south-east.

“In that direction was Glasgow and, a little closer, the American submarine base on the Holy Loch. Both, I knew, were bound to be Soviet targets if a nuclear war broke out.

“Would it be possible, I wondered, to see from where I sat, the resulting mushroom clouds that would spell my own, my family’s and everyone else’s annihilation – if not from the blast, then from the death-dealing radiation we had all been told would follow on a nuclear strike.

‘There would, as we know now, be no nuclear war that October afternoon with the Soviet convoy stopping short of trying to break America’s blockade.”

Prof Hunter added: “In large part, I think war was averted in 1962 because the Russian leaders of that time, for all the threat they may have posed, were men who had seen, in the wake of Nazi Germany’s 1941 invasion of their country, the horrors that war – even non-nuclear war – inevitably brings.

‘These men were not given to taking rash risks. But their current successor in the Kremlin (Vladimir Putin) isn’t like that.

“This is our misfortune – the misfortune, in particular, of Ukraine.”

Former Aberdeen councillor and local historian John Corall has plenty of emotive memories of different crises during the Cold War.

He said: “I remember the time of the 1956 Hungarian uprising, the 1962 Cuban missile crisis and the Czechoslovakian invasion of 1968 by the Soviets.

“I was born in 1946 and moved to Rosemarkie in the Black Isle in 1948.

“My father, a veteran infantry man of the African, Sicily, Italy and France campaigns, joined the Civil Defence Corps a year or so later.

“He would go away for regular meetings but seldom spoke about these. The only time must have been in 1956 when we thought there would be another war.

“We also thought there would be widespread annihilation and the advice was ‘never look out the windows for the flash will burn out your eyeballs’.

“We all knew there was a four-minute warning and that water was very precious and could not be wasted, because you could live without food but not without water.”

He added: “You can see three of the Civil Defence films in the secret bunker in Fife.

“Two have been shown on terrestrial TV but one has never been allowed to be shown to the masses because it is just too terrifying.

“The film-makers had experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and witnessed the horrific injuries of victims who had survived the initial blasts.

“The third film portrays a ‘Mad Max’ scenario where the police have to shoot people who “might” survive, so there was enough food for those who ‘should’ survive.

“The establishment fear was widespread civil unrest at that point.

“As children, we just accepted there could be war at any time and the testing of the air raid sirens reinforced that feeling.

“It really didn’t phase us unduly, but we did think that some of us would be blown to smithereens.”