Why go round something if you can go over it?

It seems self-evident.

But it wasn’t that obvious to the powers that be in the 1960s when it came to how to open up the northern Highlands to development and commerce.

They stubbornly resisted the idea of building a direct route north from Inverness over the three firths: Beauly, Cromarty and Dornoch.

They preferred the idea of building a dual carriageway around the heads of the firths, in spite of it being much longer and leaving a wake of destruction of prime arable land and unspoiled townships.

But they didn’t bank on the fierce resistance of three men, equally determined to protect the Highlands from a ‘Dingwall Autobahn’ and to take the A9 straight over the firths.

Against overwhelming odds, the resistance movement won, and the three firths now have bridges, taken for granted 24/7 by streams of traffic heading north and south.

Crossing the firths considered too difficult

Centuries earlier it had been decided that this was too difficult, given the Highlands’ challenging terrain.

The perception lingered, to the extent that by the 1960s, politicians and Highlands and Islands Development Board (HIDB) wanted to press ahead with their plan to build a dual-carriageway around the heads of the firths.

Villages like Beauly, Muir of Ord and the town of Dingwall would be badly affected, the road going straight through and destroying the parking in Beauly Square, for example.

It took a Sixth Form conference at Inverness Academy on the theme ‘Which Way Ahead for the Highlands?’ to spark a change to the course of this way of thinking.

Edderton farmer Reay Clarke was invited to speak to the pupils.

As chairman of the NFU’s Easter Ross Land Use Committee, he had been active in defending Highlands’ best arable land at three public inquiries into the aluminium smelter, chemical refinery and housing project in the Invergordon/Alness area.

To Reay, HIDB’s plan made no sense

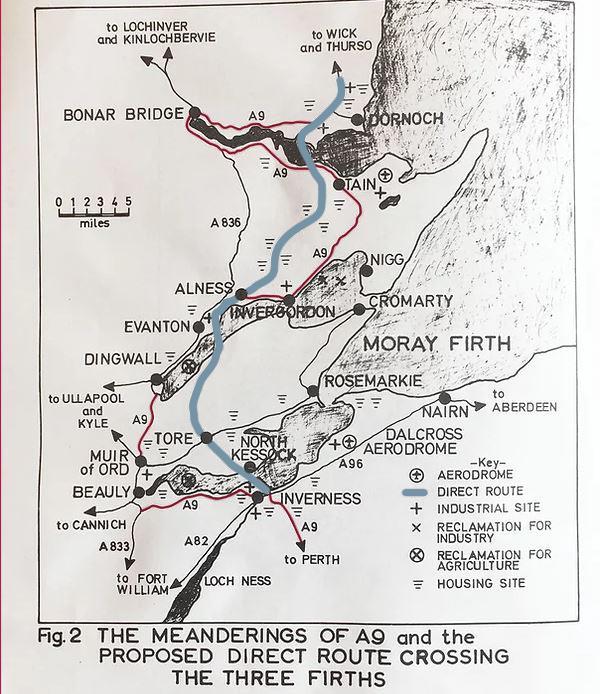

He and Dr John S Smith, a senior lecturer in geography at Aberdeen University, sat down together and re-drew the map of the Moray Firth Basin, taking all the HIDB proposed development off the Class I agricultural land and moving it to Class IV ground.

When that had been done it became obvious that the correct route for the trunk road was directly across the firths, connecting the south with Tain, Sutherland and the whole of the north.

Hanging up the new map at the school conference, he told pupils that getting to Invergordon straight across the firths would be 15 miles shorter, and they were interested.

So was a reporter from The Scotsman attending the conference that day.

He invited Reay to write an article on the proposals for a direct route north over the firths.

Game-changing article published

The article was published in early May 1969, and ended up changing the course of north history.

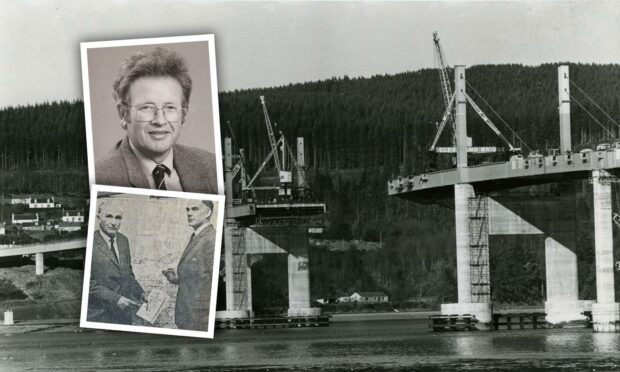

Major Pat Hunter Gordon, head of A.I. Welders of Inverness, spotted the article and phoned Reay Clarke for a meeting.

He needed little convincing of the plan and from then on took charge of managing the Three Bridges project.

Reay Clarke, John Smith and Pat Hunter Gordon together wrote a pamphlet arguing the case for the bridges, and this became their main weapon.

It was the start of a long battle

Pat wrote to everyone he could think of who might help the case, gathered more and more evidence, and went to the press.

But the HIDB was bitterly opposed to the idea, and because they were opposed, the Scottish Office was also against it.

They preferred and promoted, their own plan.

In the end, it came down to hard cash.

After a general election and change of government in 1970, a new Scottish Secretary was appointed, the Rt Hon Gordon Campbell.

Already favourable to the three bridges idea, he ordered a survey to be carried out on eight possible routes for the main road north from Inverness.

HIDB’s route came out at almost £3m more than bridging the three firths.

“The shortest distance between two points was still a straight line and the shorter the road, the less the cost, even with three firths to bridge,” Reay said.

With victory came new challenges

The nature of the massive challenge then changed to technical, costs, contracts and land acquisition.

Communities had to be by-passed, sometimes causing lingering bad feeling.

It took a decade after the publication of the pamphlet for the Cromarty Bridge to open in 1979.

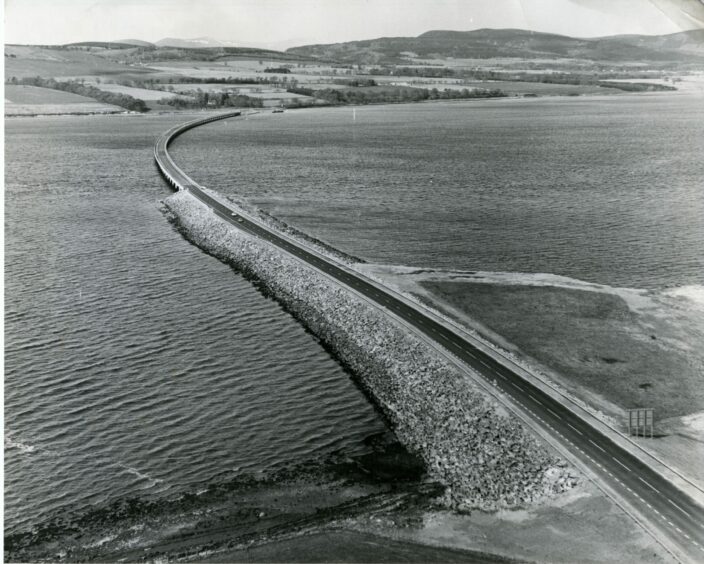

Celebrating its 40th birthday this year, the Kessock Bridge opened in 1982.

Ten years later, the Dornoch Bridge was completed.

The bridges transformed road transport in the Highlands, bringing untold economic, social and tourism benefits.

The Kessock bridge is credited as being a key factor in the growth of Inverness.

What became of the the three bridge visionaries?

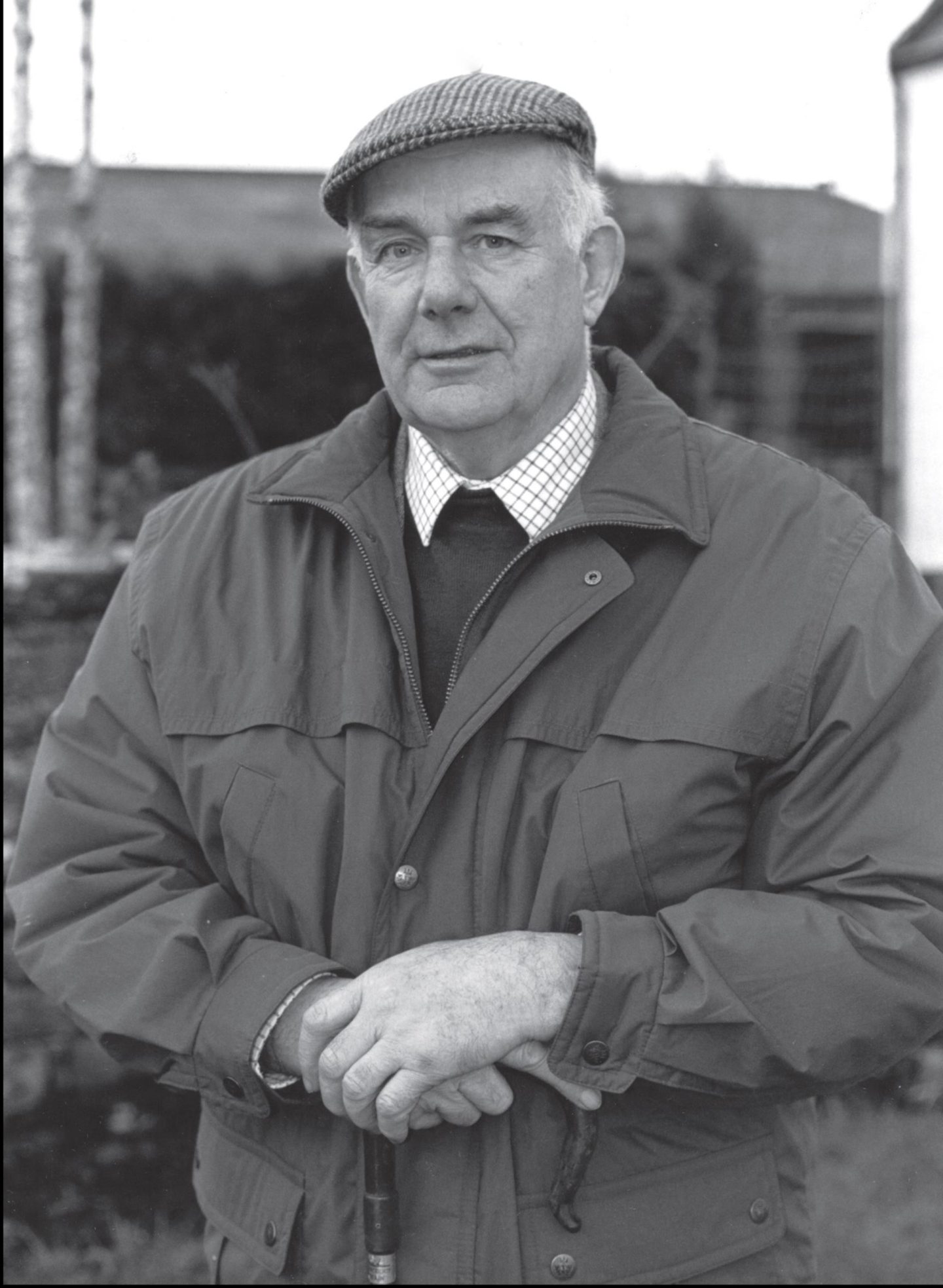

Reay Clarke was the first to drive a car over the final crossing, Dornoch, in 1991.

He continued as an active member of the agricultural scene, creating 400 acres of award-winning woodland in Edderton.

He was chairman of Edderton community council, and a lay preacher; in 2014 he published Two Hundred years of Farming in Sutherland: The Story of My Family.

He was an Arctic Convoy veteran, campaigning for veterans to receive an Arctic Convoy medal.

He died aged 93 in 2017.

Tarradale House connection

Dr John S Smith continued his distinguished academic career at Aberdeen University, with many publications behind him.

His in-depth knowledge of the northern Highlands was strengthened by his marriage to Gillian Campbell, a secondary school teacher from Dingwall.

John became involved in the practical management and upkeep of Tarradale House, the university field centre near Muir of Ord, from the 1960s.

The openings of the bridges were among his proudest days, wrote his son John upon his death in 2004 of meningitis.

Pat’s untimely death

Industrialist Pat Hunter Gordon didn’t live to see the first bridge open.

His loss in a car accident in 1978 is still viewed as a cruel blow to the Highlands.

During his time in charge, AI Welders increased turnover from around £400,000 to £2.5m.

He knew only too well the problems caused to industry by poor transport links, and was determined to develop industry and create employment in the Highlands.

When oil was discovered in the North Sea, he saw that it would create plentiful jobs, but his concern was that it should develop in such a way as not to destroy the Highlands and its people.

A good transport system was vital, hence his willingness to join with Reay Clarke and take on the battle for the three bridges.

At the time of his death he was involved in countless strategic committees and fellow of many institutes; was selected as a prospective Parliamentary candidate by the Inverness-shire Conservatives; was deputy-lieutenant of the County of Inverness, a Justice of the Peace, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and was made a CBE in the 1976 New Year’s Honours list.