His life sounds like the screenplay of a Hollywood movie – which is perhaps appropriate when you consider that Neil Paterson was one of the few Scots to win an Academy Award for his work.

But what a journey it was for this lad o’ pairts before he even started crafting scripts at his cherished typewriter.

There was his time as a gifted student at Banff Academy and talented footballer at Buckie Thistle, who moved on to excel as an amateur at Dundee United, even before he was involved in some remarkable acts of heroism during the Second World War.

If he had sought out a quieter existence after surviving hellish scenes of conflict, nobody could possibly have blamed him.

But instead, Neil turned his hand to literature, not only producing his own literary works such as The China Run, which was acclaimed as Book of the Year by The New York Times, but also adapting novels for the big screen and succeeding in Tinseltown.

It led to him helping to transform John Braine’s controversial kitchen-sink drama Room At The Top into a successful, albeit scandalous movie for its time – and although his screenplay was pitted against such rivals as Ben-Hur and Some Like It Hot in 1959, he walked away with the coveted Oscar.

It has all the trappings of a Boy’s Own adventure, even if he was never comfortable about being described as a “hero”.

Yet he features in a new book written by David Findlay Clark, who worked for nearly 40 years in the NHS as a consultant clinical psychologist after graduating from Aberdeen University.

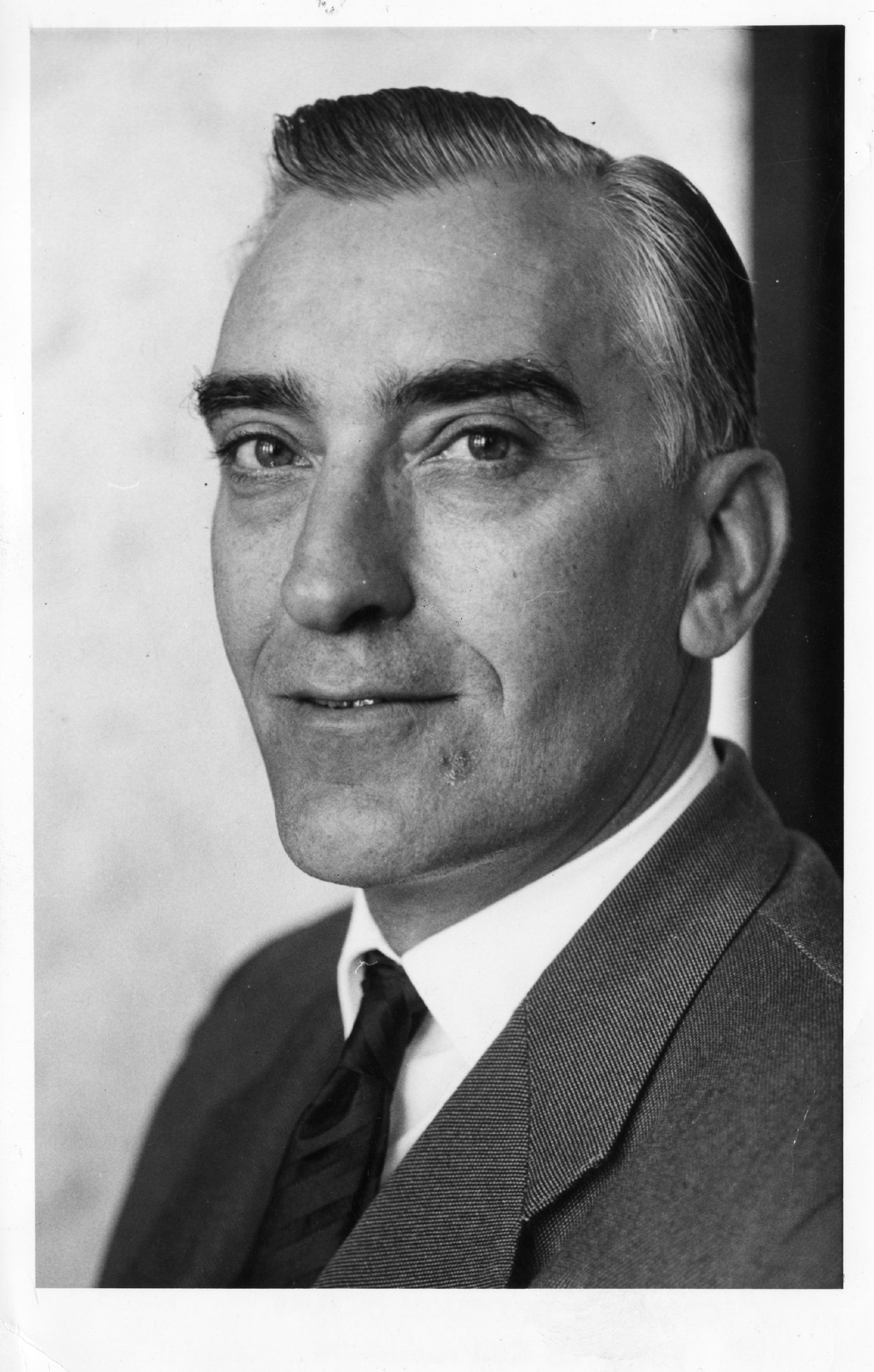

What emerges is a portrait of a modest character with deep reserves of grit and resilience, which he applied on and off the pitch.

He was proud to become captain of the Tannadice team during their 1936-37 campaign and scored nine goals, including a hat-trick in his 26 appearances for the club.

But despite being urged to turn professional, Neil had already developed an ambition to get involved in writing and journalism and joined DC Thomson shortly before the dark form of Nazism spread its tentacles across Europe.

Like many of his generation, he answered his country’s call when the hostilities began.

Also like many others, it shaped the rest of his life after he joined the Royal Navy and served as a lieutenant on the destroyer HMS Vanessa.

Mr Clark was honoured to meet Neil while the two were in Banff, yet soon enough, there were privations and tragedies for his older compatriot to endure, including a lethal and terrifying assault from German planes while his ship was on patrol in the North Sea in the summer of 1941.

The Vanessa was struck amidships, which blew up one of her funnels, some steel rigging and parts of the steel superstructure, but there was greater peril ahead as the enemy aircraft moved in to complete their mission.

Mr Clark said: “All this time, the Stuka dive-bombed and caused the ship’s boilers to explode, killing nine sailors and seriously wounding 17 others.

Bombs exploded on either side of him

“With only five officers, including the captain, who had to remain on the bridge, Lt Paterson was struggling, on a wet and erratically moving deck amid the devastating noise of the gunfire, Stuka cannon fire and bombs, to assess whether the ship might continue to float.

“As he clambered over the wreckage on deck, another bomb exploded a few metres from the ship’s side, showering Neil with sea water and debris.

“As he was struggling to free the body of the sailor trapped in the wreckage, he saw that it was the same young seaman who had brought him a mug of tea on the bridge only an hour before.

“Although the destroyer was out of control, and constantly under bomb and cannon fire attack, Neil persisted in freeing trapped and wounded seamen from the tangle of wreckage with shrapnel, and the unearthly screaming sirens of the dive bombers and the rattle of Vanessa’s ack-ack guns.”

Naturally, these experiences took their toll on the young lieutenant, but he seems to have been more concerned about the fact he had the opportunity to return home after the war while so many of his comrades perished.

Indeed, there is one telling moment in Mr Clark’s book where the sheer futility of what Neil witnessed is laid bare in a short, staccato burst of words.

As he said: “With the adolescent temerity of my years, I did once ask Neil if he had ever been afraid. ‘David’, he replied, ‘In action, I was just too damned busy and when my young, keen crewmen were killed, I was just too furious at the terrible waste of lives’.

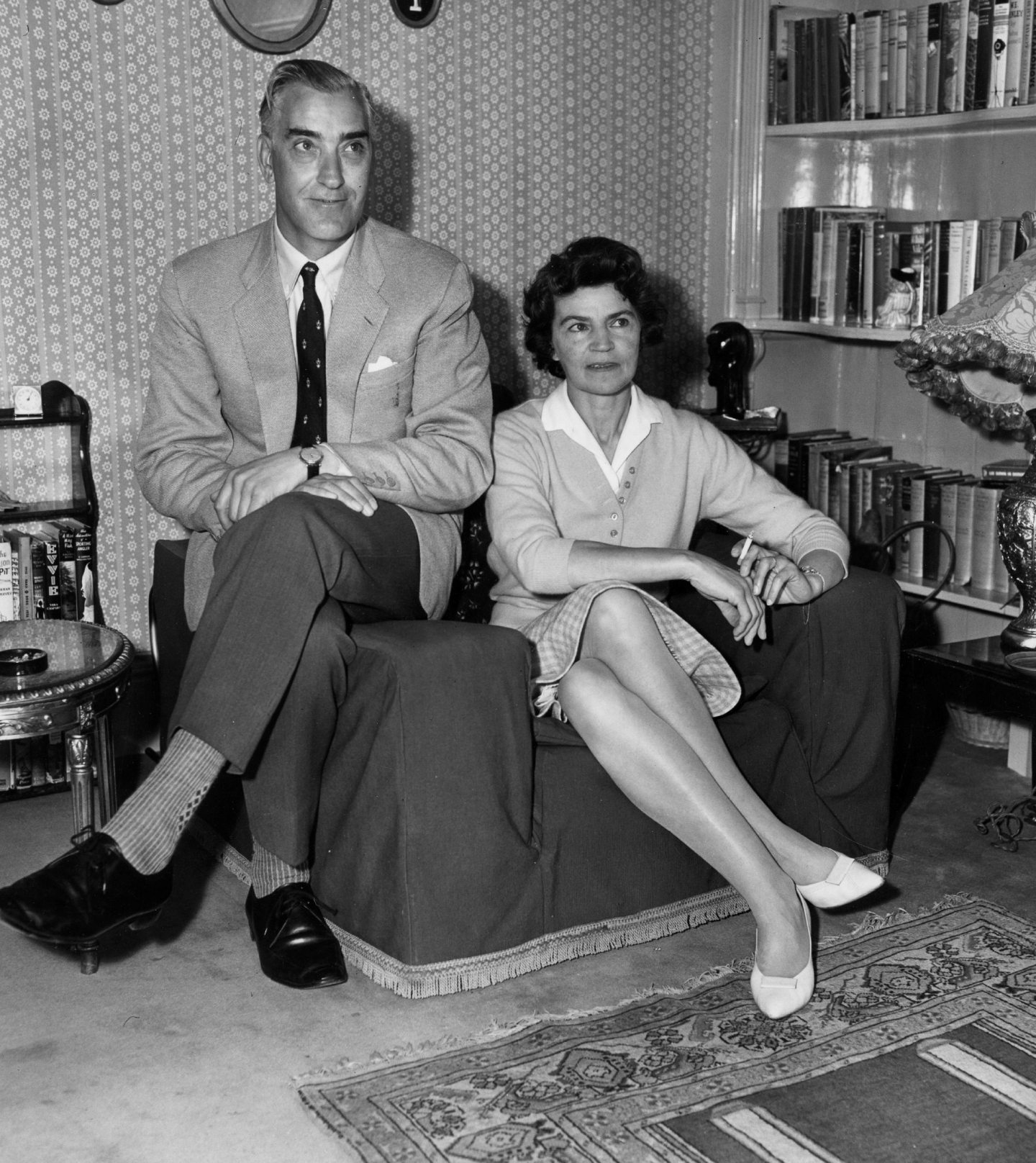

“Rose (Neil’s wife) told me after the war that Neil would often be rather quiet on his leaves (from service) caused by the damage to his ship. His writing was a kind of solace to him.”

50 years since the remarkable Neil Paterson, Dundee United’s last amateur captain, won Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar over the favourite Ben Hur. He stayed in Scotland instead of going, was told in a dawn phone call, and didn’t bother mentioning it to his kids at breakfast #Oscars pic.twitter.com/80xZZDwgcG

— Neil Forsyth (@mrneilforsyth) February 9, 2020

There are some parallels here with Neil’s compatriot, Alistair McLean, who took part in the treacherous Arctic Convoys to Russia and subsequently became the best-selling author of such novels as HMS Ulysses, Where Eagles Dare, Ice Station Zebra and The Guns of Navarone.

In common with McLean, he also wrote about ships and the sea in The China Run, which described the adventures of Christian West, the captain of a tea clipper who has to deal with life as it happens, not as he’d like it to happen.

It was an immediate success, gained glowing reviews in Britain and the United States and, in the next few years, Neil adapted his own short story, Scotch Settlement, into a screenplay called The Kidnappers.

It was a box-office smash in 1953, won honorary Oscars for its two child stars, and suddenly, he found himself the toast of Hollywood – at home in Crieff!

His wife, Rose, and son, John, always described him as ‘quiet, modest and thoughtful’; in my view, like all true heroes.”

David Findlay Clark

There were never any airs and graces about this redoubtable individual, who resisted the temptation to relocate Stateside and wasn’t even present when his adaption of Room At The Top earned such kudos at the Academy Awards – and, in the process prevented Ben-Hur from amassing a twelfth Oscar.

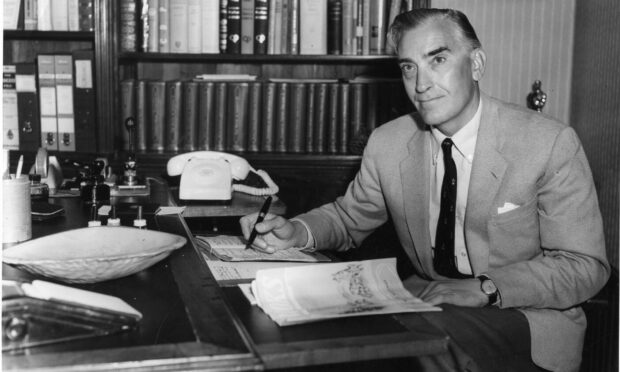

On the contrary, he received the news in a dawn phone call to his Perthshire home, didn’t tell his children while they were eating breakfast together, and didn’t so much avoid the limelight as ignore it altogether.

Yet, once again, even as he was creating new scripts and devising fresh ideas from his fertile imagination, another grand plan sprung into his mind.

And that was to be the catalyst for the formation of the British Film Institute.

It was merely another exploit on this extraordinary man’s CV, but it testified to his philosophy that he had no interest in looking backwards.

Mr Clark said: “He was a governor of the National Film School, and a governor and founder member of the BFI.

“Nearer home, he was also an executive for Grampian Television and a governor for the Arts Council.

“His wife, Rose, and son, John, always described him as ‘quiet, modest and thoughtful’; in my view, like all true heroes.

“But he always considered that his greatest triumphs were while he was playing football for Dundee United.

He never wrote about his life in war

“Of his wartime heroics, in the course of which he was nearly killed, he said very little to me or his family, nor did he write, even in impersonal terms, of what his crew and senior officers saw as his imperturbable bravery.

“He died in Crieff in 1995 after a long illness.

“Personally, I cannot understand why such an outstanding former Banff Academy pupil and national hero in so many diverse ways has never, to my knowledge, been honoured by his hometown. Maybe they did not support Dundee United!”

There was one poignant handover of a prized artefact to Mr Clark from the family of the man he had first met as a schoolboy in the 1940s.

As he said: “I was thrilled and honoured when Rose came to Banff, after Neil’s death, to present to me, expressly fulfilling his wish, a signed copy of his first novel, The China Run.

“I value it and my warm memories of the man. Heroism takes many forms, but heroes are always modest, imperturbable, quietly aware of and generous to others.”

Truly an epitaph fit for a hero.

- Secret Heroes is published by the Banff Preservation and Heritage Society.