The recent discovery of Ernest Shackleton’s ill-fated vessel Endurance has struck a chord with many people across the world.

There’s something compelling about that fabled expedition more than 100 years ago which came so close to catastrophe, but ended with all the crew members being rescued after years when they were existing on a diet of penguin and seal meat – and an alcoholic beverage called ‘Gut Rot 1916’ – and wondering whether they would ever see Blighty again.

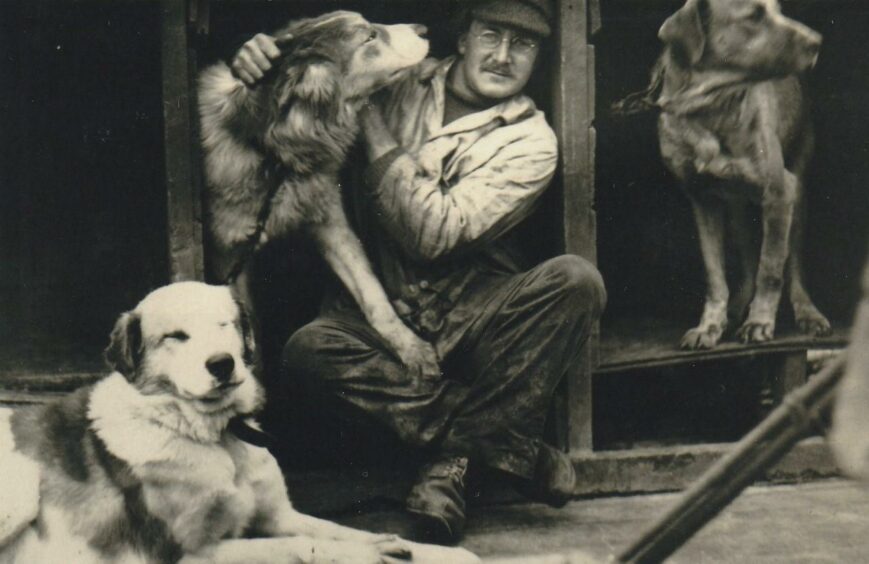

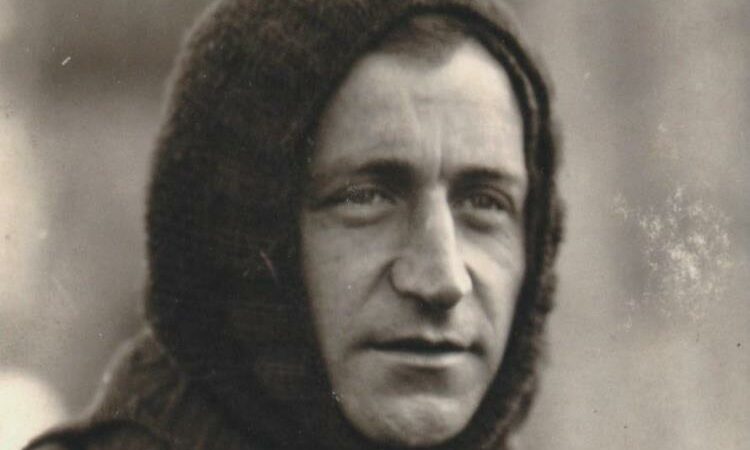

Nobody lost more when the ship sunk under the frozen waters than Aberdeen zoologist and biologist, Robert Selbie Clark, who had continued his scientific dissections and cataloguing of myriad samples with the beetle-browed industry of a true boffin after Endurance was trapped in solid Antarctic ice.

However, all his efforts were dashed along with the ship as he and the rest of the crew scrambled to safety in 1915 and started their long vigil.

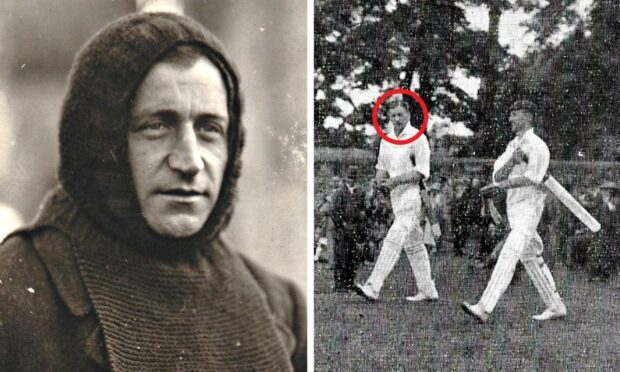

But if he was regarded as a rather dour character, who never used two words where a grunt would suffice, by some of his colleagues, Clark was a rugged, redoubtable individual with a love of cricket who represented Scotland before and after the Great War, during which time he worked on a minesweeper.

And it’s time to pay proper tribute to this unsung north-east stalwart.

Life and times of a pioneer

Born in 1882, Clark was fascinated by science and the minutiae of animal specimens from an early age and, after attending Aberdeen Grammar School and graduating from Aberdeen University, he moved to Plymouth where he was asked if he was interested in joining the crew for the polar trek.

Initially, he turned down the invitation and although he changed his mind, he was swithering so much that he, quite literally, almost missed the boat and arrived just half an hour before Endurance sailed off into the blue yonder.

In the early stages, as the Scot jotted down his thoughts in a diary, it was obvious he was far from convinced that he had made the right decision.

Just days into the voyage, he wrote: “I cannot think what I am doing here and I shall certainly return from Buenos Aires as soon as possible.”

None the less, whatever reservations he may have harboured, he was in his element once Endurance had reached the Antarctic and earned respect for knuckling down to such tasks as scrubbing the decks in atrocious conditions.

Clark, who had already represented Scottish Counties and Scotland at cricket against India and Ireland in 1911 and 1912, was a quixotic individual.

According to Shackleton, there were some days where he was garrulous and even outgoing and others where he was morose and almost callous in the way he dismembered and dissected a diverse selection of marine wildlife.

But he had no fear of the unknown and frequently embarked on potentially hazardous trips onto the pack ice in his pursuit of knowledge.

On one occasion, Shackleton wrote: ”We heard a great yell from the floe and found Clark dancing about and shouting Scottish war cries; this was after he had secured his first complete specimen of an Antarctic fish.”

As months passed and the crew struggled to maintain their morale, they noticed their colleague methodically amassing a vast amount of samples.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, he was not the most popular shipmate as a result of his continuous dissecting of specimens in preparation for curing, but he kept discovering new species, compiled copious notes, and assembled his own little private laboratory which he hoped would shed new light on Antarctic life.

Sadly, from his perspective, the gradual disintegration of the Endurance scuppered his plans and all his specimens perished with its sinking. (Although who knows what might be discovered now the ship has been located?)

Yet, despite that setback, he proved himself a resourceful figure, constantly unearthing new artefacts in the midst of adversity – and, when the men around him were in need of a tonic, he came to the rescue with the creation of an alcoholic concoction which he labelled “Gut Rot 1916”.

It sounds like something which BrewDog might have conjured up and was probably undrinkable in most circumstances, comprising as it did methylated spirits, sugar, ginger and water. But it did the trick amid the blizzards and the months of near perpetual darkness on Elephant Island.

His brew was regularly drunk on Saturdays, accompanied by jocular toasts of “To wives and sweethearts – may they never meet!”

No matter what obstacles faced him, Clark proved indomitable. Some of his confreres were ground down by the inhospitable, barren existence on Elephant Island, where neither their clothing, nor the sleeping bags were ever completely dry, but he was was stoical in their midst.

Food supplies were limited, fuel was scarce and monotony reigned, but this outwardly taciturn fellow never succumbed to despair or depression.

Finally, in August 1916, they were rescued by Shackleton aboard the Chilean ship Yelcho, four months after he had departed the island, but while some in the party sought a quieter life after their ordeal, that didn’t suit Clark at all.

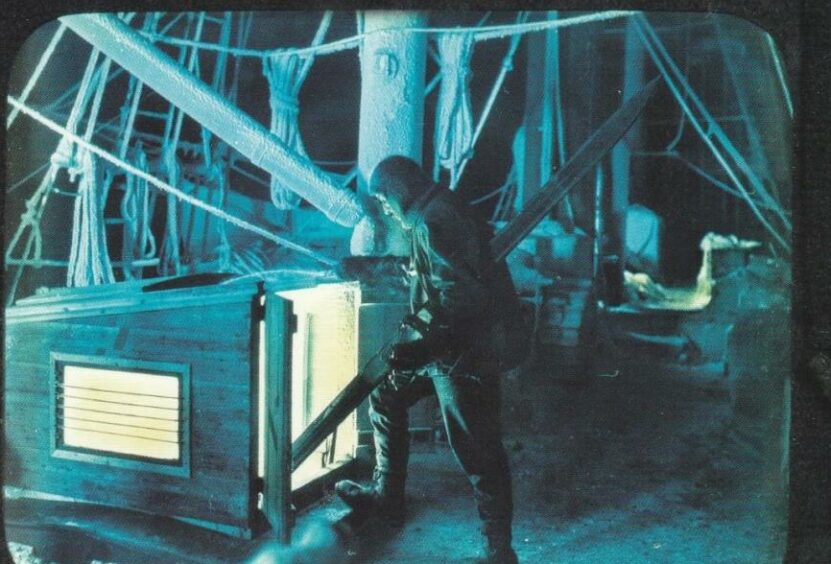

Instead, upon returning to Britain, he was determined to help the war effort and enlisted in the Royal Navy as a lieutenant on minesweepers in the North Sea for the remainder of the hostilities.

It was often dangerous work, but again, he was sangfroid personified. Akin to his Aberdeen friend, Alexander Macklin, he admitted to feeling guilty at having missed so much of the conflict.

The least he could do was serve his country and, no matter the cussed streaks and air of defiance in his temperament, the bottom line was that it was better to have this man as your friend rather than your enemy.

When peace was restored, he returned to the scientific world. But, even as he passed 40, he still had the cricketing bug and earned a Scotland recall.

Clark, widely regarded as an outstanding opening batsman, continued to turn out for Aberdeenshire and Carlton and in 1924 won a further three caps for his country – against Yorkshire and twice against the touring South Africans.

In the following year, he scored an unbeaten 97 for Aberdeenshire against Forfarshire and, in 1926, gained the last of his representative honours, in this instance for Scottish Counties against The Rest in Dundee.

In common with so many other players of his generation, his career at the crease was interrupted and hampered. But it was always just a game for him.

And that was that, from a sporting perspective. However, Clark never stopped pursuing his scientific interests and became the director of the Fisheries Research Laboratory in Torry in Aberdeen, where he worked for many years.

If he hasn’t become one of the better known of the Shackleton group, that’s as he would have wanted. A naturally introspective person, he could express himself with a bat, but he was always happiest in his academic studies, charting the uncharted, recording the unrecorded.

Robert Selbie Clark retired in 1948 and died two years later in Murtle in Aberdeenshire.

His name deserves to be properly recognised.

More like this:

Ernest Shackleton asked Dundee jute baron for £50 – and set sail on Endurance with £24,000 cheque

Aberdeen’s Alexander Macklin went to the end of the earth with Ernest Shackleton