They were the workers who journeyed to the other side of the world and became involved in a massive construction project.

They hailed from myriad communities, including Peterhead, Inverurie, Kemnay, Bucksburn… anywhere families had grown up as part of the granite industry that employed so many people throughout the north east.

The men signed up to the venture, conscious it would mean a lengthy voyage to Australia and a gruelling schedule for an indefinite period.

They would have to leave everything behind them with no guarantee of success.

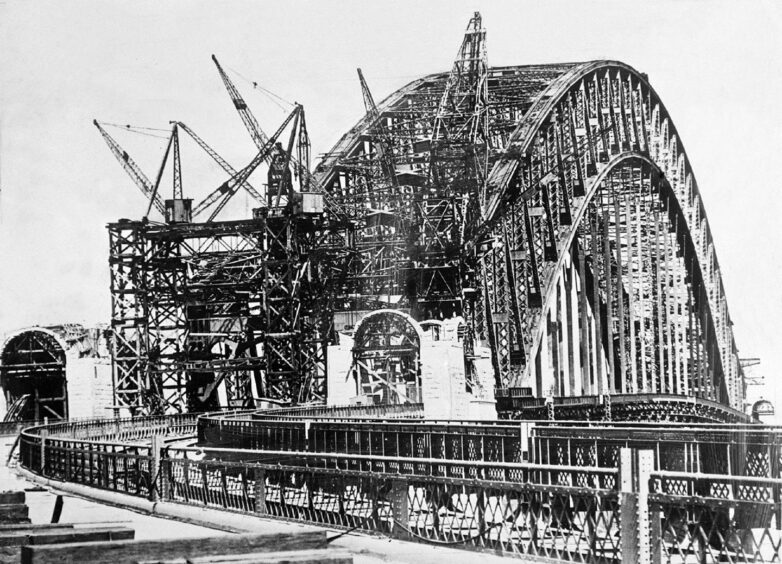

Yet hundreds accepted the challenge and were among the creators of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, which is celebrating its 90th birthday this month.

Such was the impact of those who travelled Down Under from Scotland that many of them ended up living in a community called Granite Town, created by a remarkable figure whose exploits have never been recognised.

As with most major building initiatives, there was no quick route to bringing the structure to fruition.

But once the contract had been awarded to British firm Dorman Long of Middlesbrough, which based the design on its Tyne Bridge in Newcastle, they confirmed their desire to recruit artisans who were experts in working with granite.

The search led them to Aberdeen.

It’s a story of a grand vision and vast ambition and one that former Scottish history teacher, Bill Glennie, stumbled across while he was in Sydney on an exchange programme nearly 20 years ago.

Now, he has told the Press and Journal why he believes the achievements of the “Quarry Scotties” should be commemorated in their homeland.

The Press & Journal reported in 1926 that dozens of men had left their roots in Scotland to embark on the arduous trek Down Under – a journey that could last months and often required passengers to undertake treacherous voyages on tempest-strewn seas.

The company had previously appointed John Gilmore, a far-travelled son of Harthill in Kintore, who had worked in quarries at Kemnay, Rubislaw, Peterhead, Brechin and Ailsa Craig – in addition to plying his trade in the United States – to manage the facility at Moruya, 200 miles south of Sydney.

The Scots were pioneering figures

Gilmore was a steely character, somebody who had embraced all manner of challenges during his life, and he responded to his new role in Sydney with the same resilience that had caught the attention of his employers.

He was backed by the director of construction for the bridge, Lawrence Ennis, another redoubtable Scot who had grown up in abject poverty in West Lothian and was determined to provide a better standard of living for his workers.

These two indomitable individuals were instrumental in ensuring that the bridge became one of the most iconic structures in the world.

Ennis was responsible for importing the skilled labour when there were not enough people in Australia to do the job and it was his trailblazing ideas and innovation which proved the inspiration for the creation of Granite Town.

Mr Glennie said: “He is Scotland’s best kept engineering secret, a man who was born into poverty and squalor on the shale fields of West Lothian.

“There were 12 people in a single-room house when he was born in West Calder, and yet he died a millionaire in an apartment block in Victoria in London, sharing an entrance with Winston and Clementine Churchill.

An early example of a New Town

“That’s social mobility for you and locating and visiting his grave in Rochester in New York was a pilgrimage of sorts.

“Ennis had first-hand knowledge of poor housing, inadequate facilities and planned towns – garden cities – were all the rage in the northern hemisphere.

“Ennis regarded Granite Town as a model township, in its own modest way.”

Jim Fiddes, who has written a book, The Granite Men, about the history of Aberdeen’s most notable material, examined how the initial flurry of interest led to scores of men departing from the north east en route to Sydney.

He said: “The Aberdeen granite industry might have been in decline after the First World War but the expertise of its workers was still in high demand.

“It was in December 1926 that the Press & Journal reported that, earlier that year, 30 men had left the city to work on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Whole families travelled to Oz

“The paper noted that letters sent home from the men indicated they were more than happy with their working conditions – and that the wage they had signed up to had already been increased by 10 shillings a week.

“When a representative from Dorman Long came to Aberdeen, he received almost 250 application forms and the first party of workers left Aberdeen in February 1926 with another group following them in May.

“Unlike most of the granite men who had previously gone to work in North America, this group took their families with them and children were born in Australia, who later moved back to Scotland with their parents.”

As the scale of the bridge project grew, people of 13 different nationalities ended up working at the site and carried out a variety of roles, with the majority fulfilling the positions of stonemasons, quarrymen and labourers.

Mr Fiddes added: “For all the north-east men who decided to set sail to Australia, the initial contract was for three years with the possibility of further work beyond that period.

“In the community known as Granite Town that grew up at the quarry – which consisted of simple houses, bachelor’s quarters, a post office, a store, a hall and a school – they were joined by Australian and Italian stonemasons.

“At the peak of the work, the population at Granite Town reached 300.”

Ennis was proud of the way the community pulled together and, despite his many other duties, made regular visits to Moruya and met the settlers in their new, albeit temporary, home.

As Mr Glennie said: “There was never any grudging recognition of Ennis’s role.

“As the bridge grew in size to dominate the city’s skyline, so too did appreciation of Ennis.

Their legacy lives on 90 years later

“He and his wife enjoyed celebrity status, mixing with the likes of the Governor-General, State Governors, the Lord and Lady Mayoress and other dignitaries at garden parties, regattas, banquets and balls and their activities were reported in the society columns of the Sydney press.”

Granite Town was transformed to Ghost Town after the project was finished, but Ennis, Gilmore and their fellow Scots had helped construct something special that would command headlines all over the globe.

On March 29 1932 Ennis was awarded honorary membership of the Australian Institution of Engineers, the first individual to be so honoured.

It was no more than he deserved for his unstinting efforts and, in his address to the members, he remarked with justified pride: “The work on that bridge is equal to the very best in the world”.

That remains true even now as it commemorates its 90th anniversary.