It was the promise of a brighter future that came back to haunt many Aberdeen councillors during the 1970s.

The local authority’s leading architect, Thomas Watson, vowed: “There will be no sea of tarmac at Seaton” when he unveiled ambitious plans for the creation of a three-phase, multi-storey housing project in August 1971.

Warming to his task, he claimed the development would be “the most imaginative and aesthetically acceptable to be built in the city to date”.

The proposals were certainly large in scale, as the administration attempted to respond to the rising population in Aberdeen, but they gradually sparked acrimony and anger as the project dragged on interminably and those responsible for the hold-ups were accused of “scandalous” inaction.

Indeed, more than a decade after Mr Campbell’s vision was launched with a fanfare of positivity, questions were being asked about what had gone wrong.

At the outset, there was little indication of the myriad delays and issues which would generate such a plethora of negative stories about the storeys.

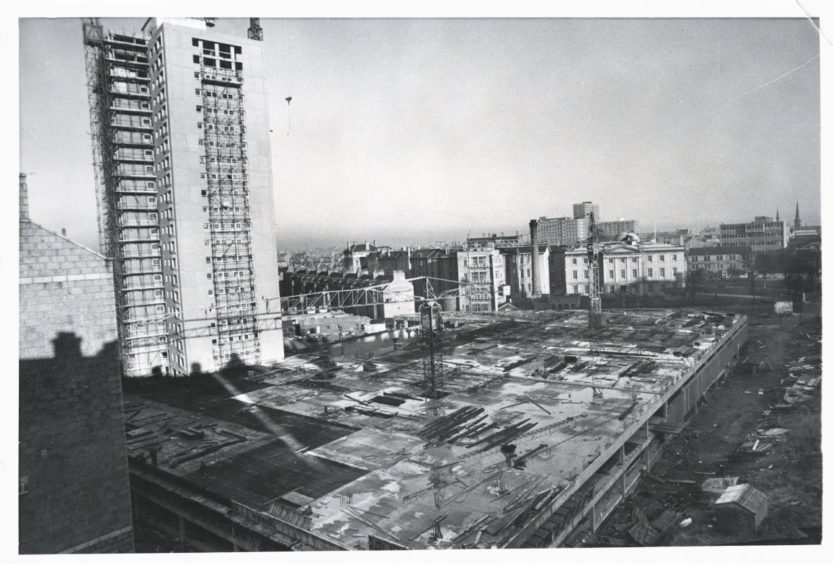

It had actually been four years earlier, in 1967, when the Press & Journal published the original plan for the Seaton high-rise initiative, after Aberdeen Corporation Housing Committee voted 16-13 to award the development of 1,053 flats to a single contractor, which in itself was questioned by members.

That was followed by revisions and tinkering and frequent re-drafting of the architectural drawings, accompanied by concerns from local residents about the impact of a giant concrete jungle on their doorstep.

And so, it all began.

Misgivings about Seaton high rises

After much discussion, it was decided in 1971 there would be 998 homes, spread over 14 towering blocks, with the cost of construction estimated at around £4.5 million – a figure which, given the spiralling inflation which sent the price of everything up in the years ahead, seemed detached from reality. (And the programme ended up costing more than double that price).

But all was sweetness and light in the early days, as councillors promised to provide parks and other amenities for those who moved into the high rises.

Fast forward even 12 months and you can start to spot the mood changing.

In 1972 the contract for the last seven multis was agreed with Peter Cameron Ltd. The sum of £3.16m was the biggest contract awarded to any single firm in the city’s history, but the venture soon became bogged down.

There were reports of bad management on site, of workers taking industrial action, of materials and tools not arriving as scheduled and, the following year, Peter Cameron Ltd was taken over by Bardolin Scotia Ltd.

Remarkably, the council had earmarked December 1974 as the completion date, which always seemed an optimistic forecast, considering the vagaries of the local climate and the giant nature of the construction scheme.

But, as the months and years passed, the frustration simmered and boiled up and went straight to the heart of the authority’s debating chamber.

The members’ misgivings were graphically expressed during a stormy session in June 1975 when Aberdeen District Council’s housebuilding committee made it clear that progress on the vast council house plan was both “scandalous” and “hopelessly behind schedule” due to repeated failings.

City architect Ian Ferguson told a group of councillors: “The present position has become serious.

“On past performance, there can be little confidence that the contractor will complete the project expeditiously.”

Nor were they reassured when they spoke to building boss Peter Cameron, who admitted that the construction had been plagued with difficulties.

This boss wasn’t carrying the can

He said: “The allegations of bad management on the site are probably true, to some extent.

“At the time (the early 1970s), a lot of people left the building trade and went into the oil industry in search of higher wages.

“It was difficult to replace a site agent with, say, 15 years’ experience and building workers in general don’t like to work on high-rise blocks.

“Quite frankly, we were also caught by inflation on a fixed price contract.

“As things stand (in 1976), Bardolin Scotia now stand to lose anything between £1.25m and £1.75m on the deal, which I hope will be finished next year.”

It wasn’t until the end of 1977 that a large group of residents prepared to move into Hutcheon Court and, even then, they were prevented from doing so during a lengthy period of industrial action taken by lift operators.

The Press & Journal reported on how more than 90 families were unable to enter their new multi-storey homes because of a nationwide strike.

It stated: “The flats have been ready for occupation for a week, but as only one of the block’s two lifts is operating, council officials have so far allowed only a small fraction of the tenants to move in.

‘We have to be mindful of safety’

“A council spokesman said: ‘If 140 families tried to move in with their furniture and personal belongings at the same time, there would be chaos.

“There is also the major issue of safety if the one lift which is working was put out of order and people were stuck in it’.

“The lift engineers’ dispute over pay – which is now in its seventh week – affects only new installations, such as those at the recently opened North Sea Court, Aulton Court and Beechview Court, all of which are in Seaton.”

The majority of those who made their new homes high in the sky expressed satisfaction with the quality of their homes and several letters in the P&J spoke warmly about the communal spirit in the multi-storeys.

But the myriad delays in the whole construction process significantly increased the lengthy queue of people looking for accommodation.

Indeed, matters grew so bad, according to a report in the Evening Express, that, as contractors struggled to meet the deadline in Seaton, fewer than 100 council properties were built in 1975 and the lack of employees in Aberdeen meant there was talk “of setting up camps or hostels for incoming workers”.

Finally, once most of the multis had opened, the Evening Express reported in November 1977 that it was most positive thing to happen that year, but the paper didn’t gloss over the strife which had enveloped the project.

It stated: “The completion of the 781-house scheme (another 217 were subsequently built at the site) of multi-storeys in Seaton was gratifying to behold, but, more than five years after it started, it has been beset by controversy before the last of the tenants has been able to move in.

“And, with more than 4,000 people waiting on council houses in the city, local authority figures are concerned about the slow progress of housebuilding.”

Many families had only been in their homes for a few years before Aberdeen City District Council – as it was known at the time – confirmed it was spending £200,000 on a survey looking into the condition of the structure of 11 multi-storeys, including seven built by Bardolin Scotia.

The P&J reported: “City architect Mr Ian Ferguson explained at yesterday’s (council) meeting that no potential construction defects had been found in the last investigation carried out.

“However, the Scottish Office had written to request a further structural investigation of all Bison-style construction.”

It wasn’t until April 1985 that they were eventually given a clean bill of health.

What began as a sprint to the heavens had turned into a marathon journey.

More like this:

The Aberdeen multi-storey dream of the 1960s that turned sour for so many residents

From tenements to high rises: The homes built to fix housing in Aberdeen