It was the cricket team that was never going to be stumped for literary flair, even if their efforts on the pitch often caught them out.

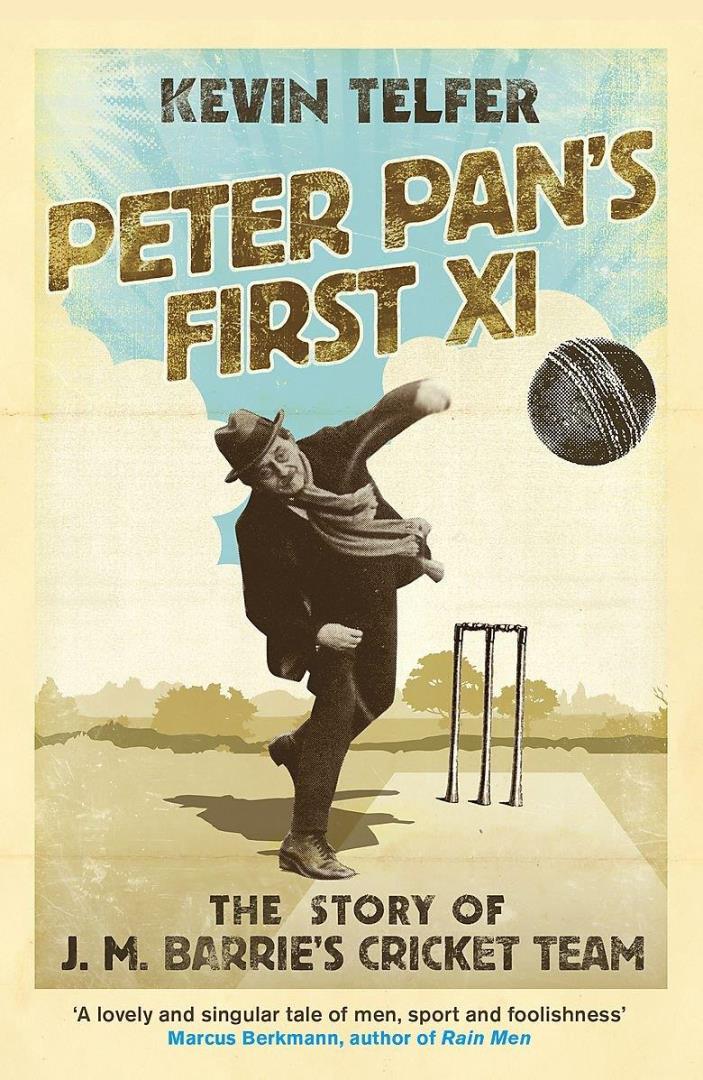

And, despite the erroneous perception of the game being an English pursuit, it was Scottish author JM Barrie, from Kirriemuir, who created the Allahakbarries in 1887 and turned them into the first celebrity sports group.

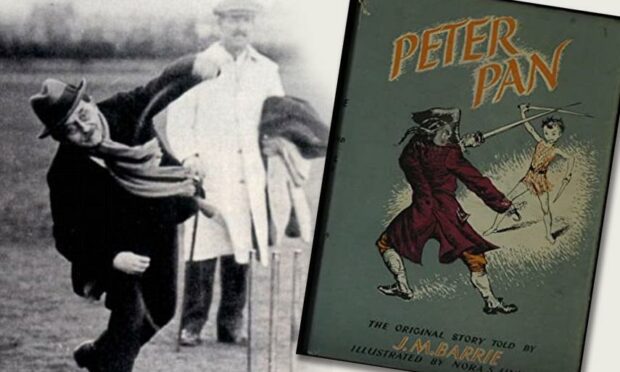

The Peter Pan author wasn’t much of a player – his achievements were closer to Never Score than Neverland.

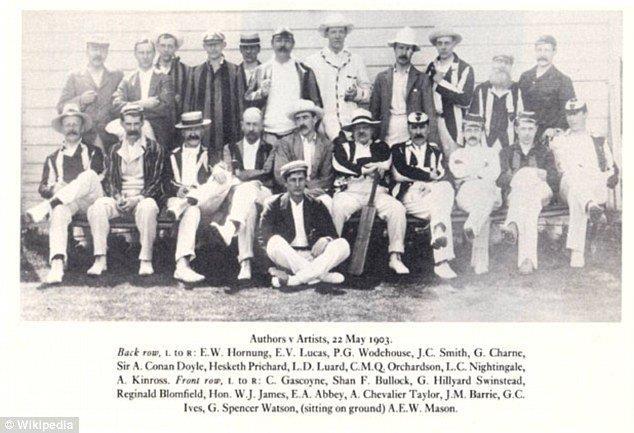

But he persuaded many of the most famous literary figures to join him on his tour of pavilions and pitches across Britain during the amateur club’s 26-year existence.

These included HG Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle (another Scot), Rudyard Kipling, PG Wodehouse, AA Milne, Jerome K Jerome, GK Chesterton and EW Hornung – who only happened to create, between them, The War of the Worlds, Sherlock Holmes, The Jungle Book, Jeeves and Wooster, Winnie the Pooh, Three Men in a Boat, Father Brown and Raffles.

So there was never a shortage of spectators when they were on the field.

Heaven help us!

If you were being kind, you would describe Barrie as one of the game’s great enthusiasts who even wrote a book about his team, which was reprinted in 1950 with a foreword by Sir Don Bradman, the sport’s best-ever batsman in terms of his unprecedented Test average of 99.94.

But, if you were being more honest, you might describe the Angus man as a futility player who was far better at talking about cricket than playing it.

Even the self-deprecating name Allahakbarries was coined after a misunderstanding. Barrie believed that the Arabic phrase “Allahu akbar” meant “Heaven help us” when its actual translation was “God is great”.

And his efforts at the crease meant he had plenty of time to sign autographs.

Yet, to be fair, Barrie was generous in his praise for teammates and opponents alike.

He told one colleague: “You scored a good single in the first innings, but were not so successful in the second” and complimented a rival club after they had been skittled for 14 by saying: “At least you reached double figures”.

He always forbade his team from practicing before a match because “it can only give them (the other side) confidence”.

And he suffered the ignominy of having his stumps rearranged by American theatre actress Mary Anderson – the opposite of bowling a maiden over – while they were involved in a village contest in 1897.

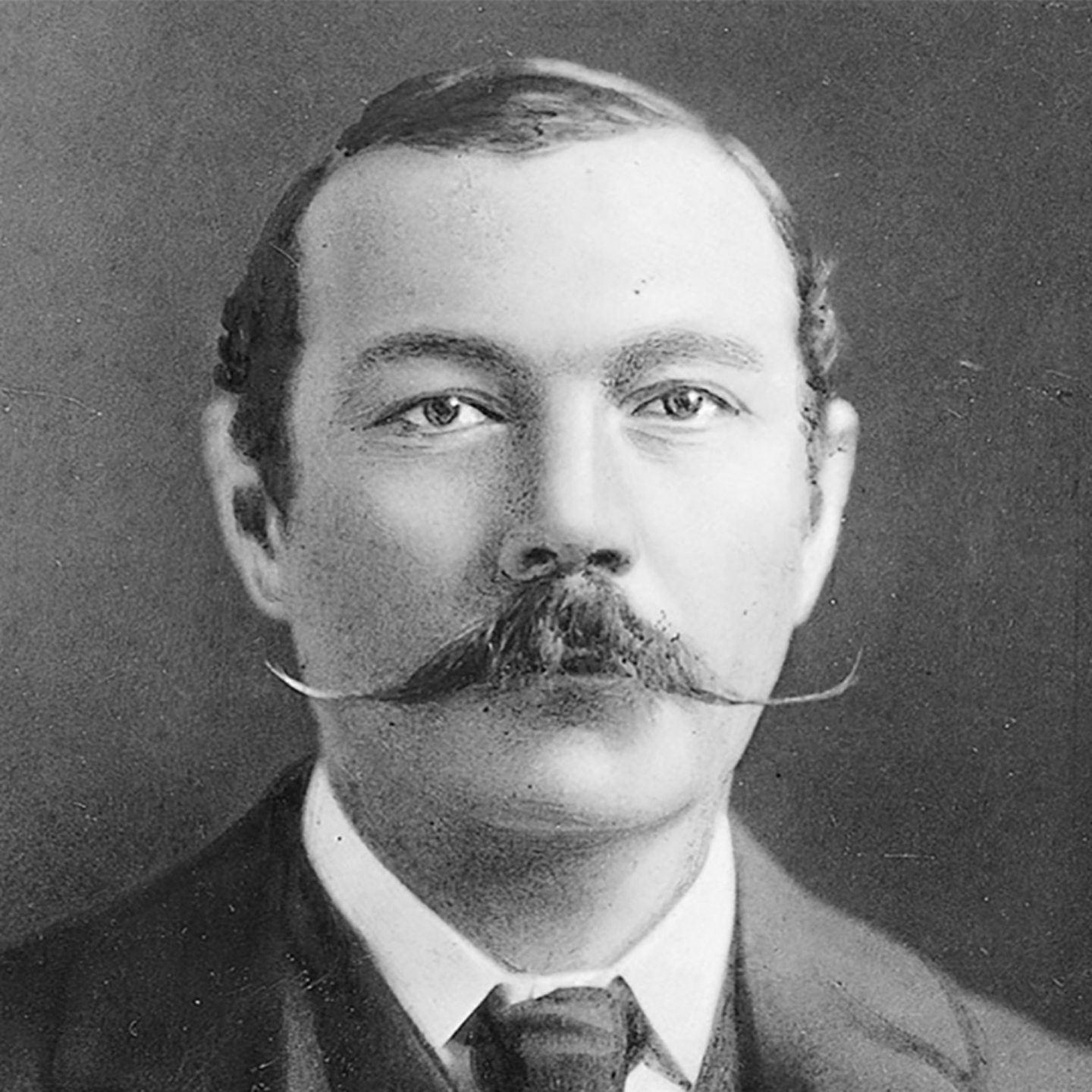

Yet, if he was a bit of a duffer, the same could not be said of his compatriot Doyle who took his sporting duties very seriously. And that attitude helped transform the fortunes of the less-than-fabulous Barrie boys.

Kevin Telfer, the author of the book Peter Pan’s First XI, has investigated the contrasting backgrounds of those who joined forces with Barrie.

And while some were clearly much happier with a pen than a bat or ball in their hand, Doyle, the fellow who wrote The Hound of the Baskervilles, was a towering figure who dogged his rivals in several different pursuits.

Kevin said: “He was a very good cricketer (whose one first-class wicket was the renowned W G Grace) and a remarkable all-round sportsman, who is credited with bringing downhill skiing to Switzerland and played football for Portsmouth (where he had a medical practice) in the 1880s.

“But this is one of the most outstanding examples of the link between literature and sport and there is something quite improbable about how these famous writers started playing together, and all their characters are quite fantastical.”

The team raised the game’s profile

The celebrities were feted on their travels and attracted the interest of people who would normally never have gone near a cricket ground.

And there were some remarkable performances, not least from Doyle, who could occasionally forget the Allahakbarries were meant to be playing for fun.

In one fixture, at Kensington Park in May 1901, he struck a typically dashing 91 and picked up eight wickets to leave “The Artists” bewitched, bothered and bewildered. Whereupon, at the age of 42, he dashed off to play elsewhere.

In another tussle, Doyle’s white flannels quite literally caught fire when a quick delivery rapped him on the thigh while he was batting, duly igniting a box of matches in his trouser pocket.

The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopaedia even suggests that, when he was striving to find a truly distinctive name for his most famous literary creation, he was inspired by the Nottinghamshire all-rounder Frank Shacklock.

And Shacklock eventually became Sherlock. All pretty elementary!

As Barrie’s renown increased, the Allahakbarries enjoyed tremendous success during what was a flourishing period for the sport across the world.

But all their exploits, Edwardian glamour and derring-do couldn’t survive heightened political tensions between the superpowers in Europe.

Indeed, a few of the younger players who featured in their final match in 1913 subsequently perished in the First World War, which brought the curtain down on this quaint enterprise.

And among them was George Llewelyn Davies, one of the boys who helped inspire Peter Pan, who was killed in 1915, the same year that John Kipling – Rudyard’s only son – died at the Battle of Loos.

Cricket was suddenly rendered a trivial bagatelle in the grand scheme of things.

But while The Allahakbarries were no more, they had managed to put a smile on the face of many people for more than a quarter of a century.

- Peter Pan’s First XI is published by Sceptre.

More like this:

When Don Bradman thrilled Mannofield and Buff Hardie was in the crowd