Why is it that some good men of extraordinary achievement are cast into obscurity by society and their peers?

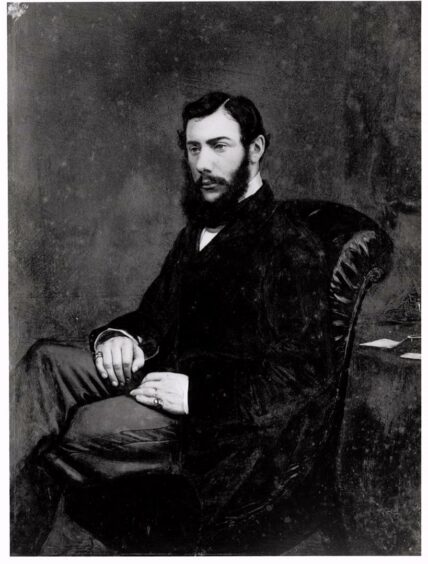

Take William Balfour Baikie, son of Orkney, surgeon, naturalist, linguist, explorer and government consul.

Through kindness, compassion and fairness, Baikie won the respect of African leaders and was able to play a key role in opening up West Africa to the British.

Yet apart from his memorial in St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, he’s been relegated to a footnote, for someone looking closely, in the annals of how Africa was explored and opened up for European trade in the 1850s and ’60s.

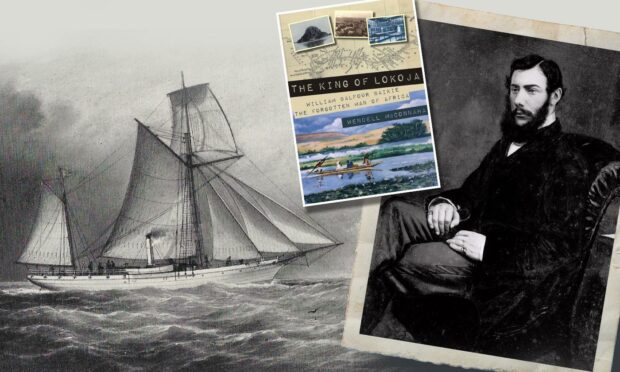

Author Wendell McConnaha has been studying Baikie for 28 years, and relates his story in his new book The King of Lokoja, William Balfour Baikie The Forgotten Man of Africa (Whittles Publishing 2022), always with an eye on the question: why is Baikie not well-known and lauded outside Orkney and Nigeria?

He was born in 1825 to a junior branch of the wealthy and influential Baikies of Tankerness, though without the money or land.

The young William was educated at Kirkwall Grammar school, and privately in a group with his brother, Balfour cousins and sons of more prominent members of the Kirkwall community.

Amiable and kind

Hints of his character emerged early, with peers saying in his obituary that “he was distinguished among his fellows by his amiability and kindness of disposition and gave early indication of that power of application and love of knowledge by which he has since rendered himself famous.”

Orkney was the source of Baikie’s love and close observation of nature; and McConnaha also thinks the long northern nights gathered around the fire telling yarns made Baikie into the well-honed storyteller that emerges in his African writing.

At 16, Baikie left Orkney to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh between 1842 and 1846.

Here he was also encouraged to develop his interest in natural history and botany- later, Baikie would mingle and exchange views with the likes of Charles Darwin among other eminent members of the scientific community.

Baikie joins Navy

In 1848, Baikie joined the Royal Navy as an assistant surgeon.

His first voyages turned out to be something of a honeymoon as he was able to collect plant and animal specimens off the coast of Syria and the Mediterranean.

Many of these are still housed at Kew Gardens, the British Museum and elsewhere.

His sea voyages came to an end for a few years in 1851 when he was appointed assistant surgeon at the Royal Hospital Haslar in Gosport, Hampshire.

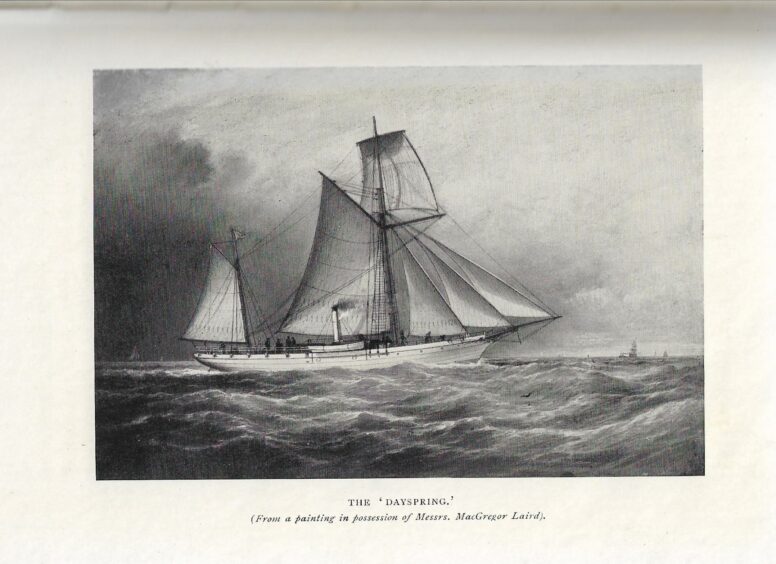

By 1854, Baikie was at sea again on a venture funded by Liverpool entrepreneur Macgregor Laird who was looking to open up West Africa to trade using steamships which could more easily navigate the key rivers into the interior.

African turning point

This turned out to be the turning point of Baikie’s life.

To sum up, he made two voyages exploring the Niger and Benue Rivers to establish trading centres for Laird, penetrating 250 miles further in than any of his predecessors.

The first expedition was a resounding success, and he also successfully conducted the first clinical trial using quinine as a preventative for malaria.

For the first time in history, his initial exploration of these rivers was conducted without the loss of a single life to fever, and it can’t be overstated what an achievement this was.

Illness, rather than attack by wild animals or humans, was by far the biggest cause of death for Europeans venturing into Africa.

Hero’s welcome

Returning to London to a hero’s welcome, Baikie was nominated for one of the Royal Geographic Society’s prestigious awards, but ultimately was not recognised.

His second voyage was a disaster.

His ship was wrecked; members of the expedition died, he failed in his mission to find Heinrich Barth, another explorer, and he was stranded for over a year in the vast remote territory known as the Sokoto Caliphate.

Following his rescue and despite gruelling challenges of every variety, he chose to remain alone in Africa for what would be his final years in order to complete his personal mission.

King of Lokoja

This is where he would be designated the King of Lokoja by the ruler of the Sokoto Caliphate, becoming a hero among the Nigerian people for his personal qualities of fairness and respect for their community.

He married a local woman, and had three sons and five daughters.

When his European clothes wore out, he adopted comfortable native dress, earning the contempt of other Europeans who accused him of ‘going native’.

He collected detailed information on nearly 50 African dialects, and his translation of the Psalms into the Hausa language was published by the Bible Society in 1881.

As an explorer he mapped and charted large sections of the Niger River system as well as the overland routes from Lagos and Lokoja to the major trading centres of Kano, Timbuctu and Sokoto.

But the toll on his health was enormous.

During the second voyage, his preventative use of quinine against malaria failed, possibly because the quality of the quinine was inadequate, the dose was insufficient, or some men stopped taking it.

Baikie at death’s door

Baikie lost faith, and gave it up himself.

The illness, and other tropical afflictions, saw him frequently at death’s door, so that in 1864 he recognised he would have to leave his wife and children in Nigeria and head back to London and Orkney for a while.

But by December 12, he was dead, in Sierra Leone where he had hoped to recuperate enough to complete reports for the Colonial and Foreign Offices before heading home.

He was 39 years old.

Things might have been different

There were a lot of ‘what ifs’ in Baikie’s life which, but for twists of fate or jealous conniving, might have put him in the establishment’s top tier of African explorers.

“Happenstance, professional backstabbing, his enlightened approach to Africa and his personal stubbornness”, says Wendell McConnaha.

Most strikingly, his attitude to Africans was at odds with one the British had developed earlier to justify slavery and hung on to.

They were morally-corrupt savages in need of ‘civilising’ and Christianity, was the establishment’s position, whereas for Baikie they were equals, worthy of respect, of learning their customs and language.

He was passionately anti-slavery, buying countless children offered to him as slaves by African leaders.

These he would either take into his own fold or send on to Sierra Leone to be educated and looked after.

His views were not popular

So his success in Africa flew in the face of every element of his government’s philosophy.

“To praise his efforts as the new, effective approach to African trade would have taken them in a commercial and, more importantly, social direction they did not believe in and were consequently unwilling to go,” writes McConnaha.

“Baikie was a true friend of Africa and a champion for the people of the Niger.

“He was also willing to give his life for his beliefs.

“Now, 150 years later, if you are white and travel along the Niger River you will be called ‘Baikie’.

“I think he would have liked that.”