An important Lochaber visitor attraction marks a major milestone this year.

Fort William’s West Highland Museum is 100 years old.

It was the vision of Onich man Victor Hodgson of Culilcheanna which brought the museum into being a century ago.

It’s not been an easy journey, taking on the 1850 British Linen Bank building in Cameron Square, funding it and keeping it habitable.

Just a few of the challenges: damp, subsidence, dry rot. A crippling mortgage. An attempt to buy it and move it to the old fever hospital. An attempt to buy it and demolish it for a new road.

Museum’s growth in popularity and stature

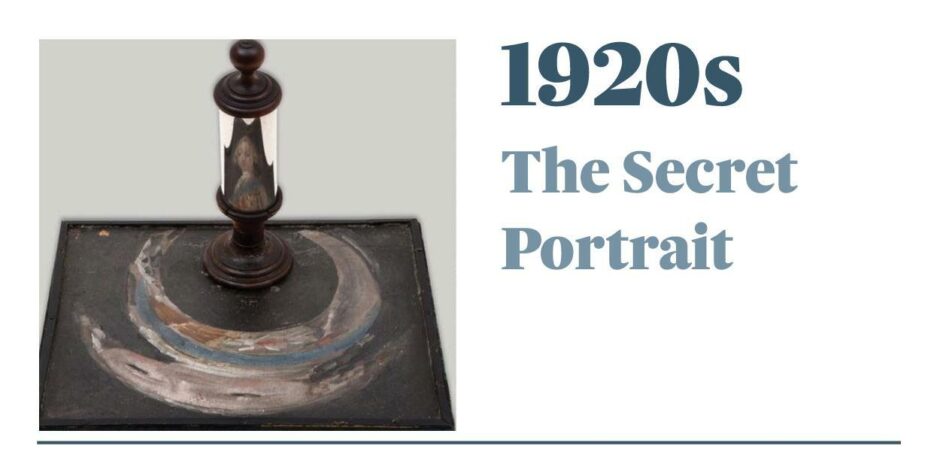

One of the first items in the collection was “The Secret Portrait” of Charles Edward Stuart which Victor found in a London junkshop.

It’s still one of the prize pieces in the collection and has been loaned for exhibitions in Paris and Amsterdam over the years.

Another significant acquisition came in 1928 the Strange Plate was purchased at auction, – a copper plate commissioned by Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1746 to print banknotes to pay his army.

The low entry fee up to World War Two saw healthy footfall, but the war saw valuable items locked away as the first floor became the Royal Navy officers’ mess for the duration.

Dwindling footfall

After the war things were a bit rocky from time to time with petrol rationing and even the 1964 typhoid outbreak in Aberdeen affecting visitor numbers.

Despite the museum’s growth and redevelopment, footfall dwindled to less than 10,000 annually, so the decision was made to make entry free, rely on donations and income from the shop, and use local volunteers.

The gamble paid off.

Pre-pandemic the museum welcomed 60,000 visitors, unheard of for fifty years.

Ten decades, ten objects

The museum has acquired some objects of world class importance during its 100 years, many of them with Jacobite significance.

Here, by decade in which they were acquired, are some of the museum’s star items.

An anamorphic portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie is painted on a tray, and can only be revealed using a cylindrical mirror.

In the 18th century it was treasonable to support the exiled Stuart dynasty, so the Jacobites devised ways like this to secretly display their loyalty. It was discovered in a London junkshop by the museum’s founder Victor Hodgson in 1924.

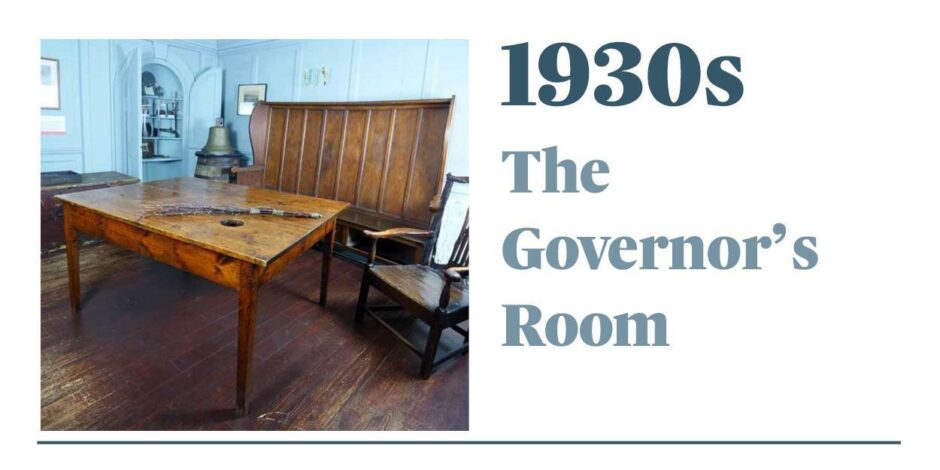

The internal paneling from the Governor’s room of the old fort at Fort William dating back to 1690. This is the room where it is thought that the order for the signing of the massacre of Glencoe was signed.

When the old fort was demolished to make way for the railway, the wooden paneling was dismantled and reassembled inside the museum in 1937.

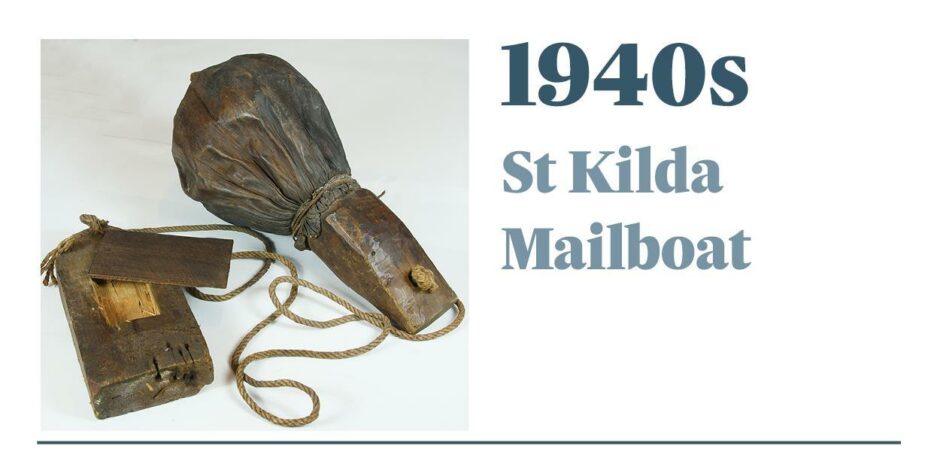

By the late 1890s, a unique system of mail dispatch had developed on the remote Scottish archipelago of St Kilda.

Letters were enclosed in a waterproof receptacle, usually a sheep’s bladder, attached to a homemade buoy and launched into the sea in the hope it would reach its intended destination. It is said that on one occasion a St Kilda mailboat drifted out as far as Norway.

This trooping helmet belonged to James Graham, 1st marquis of Montrose. Montrose was a Scottish nobleman poet and soldier.

He initially joined the covenanters in the wars of the three kingdoms, but subsequently supported King Charles I, as the English Civil war developed. He has a close association with Lochaber as the Second Battle of Inverlochy in February 1645 was one of his greatest victories.

Marching his men across the frozen foothills around Ben Nevis, Montrose surprised and defeated his enemy.

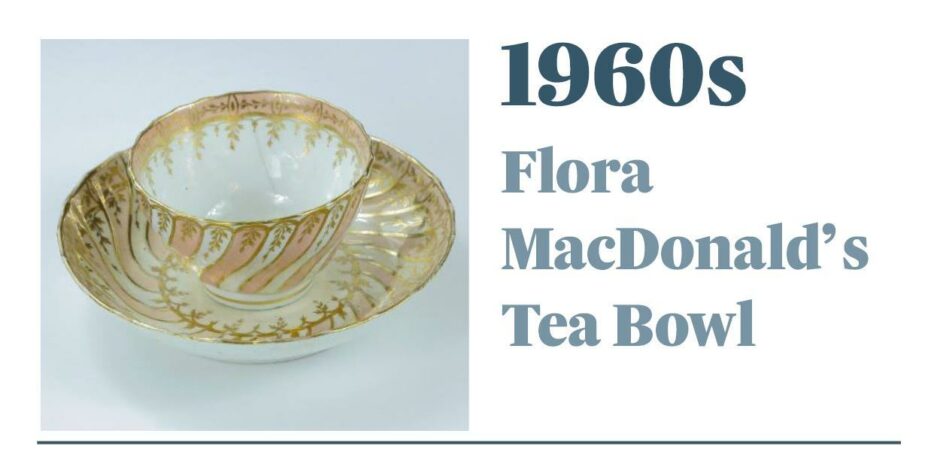

A fluted white handleless tea bowl with a deep saucer. Decorated with pink and gold enamel, both pieces are adorned with gold floral motifs and gilded gold leaf.

This teacup would have been part of a set belonging to the Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald, who famously helped Bonnie Prince Charles escape Hanoverian troops in 1746 after his defeat in Culloden.

This set of French bag pipes known as a musette are extraordinary as they may once have belonged to Prince Charles Edward.

They are made of wood with leather bellows, a velvet bag and are covered in lace trimmings, keys and fittings are made of ivory.

This is a typical 19th century Highland outfit made for a child. It compromises of a kilt, jacket, sash, sporran and Glengarry. It belonged to Donald McNaughton who wore it when he was 5 years old, living on Skye.

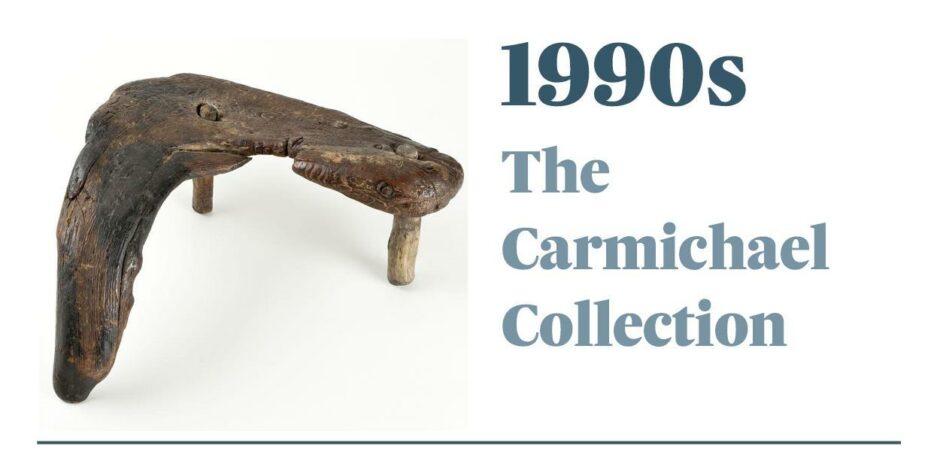

A tree root stool from The Carmichael Collection, an important collection of objects gifted to the museum in 1992 by the descendants of Victorian folklorist and collector Alexander Carmichael.

Legend has it that three sisters living on a croft on Uist provided food to Prince Charles Edward Stuart one evening when his party passed through the area when they were on the run from Hanoverian troops in 1746.

When the sisters realised who their visitor was, they quarrelled as to who should keep the stool. A label on the item reads ‘Stool on which Prince Charlie sat when in hiding in Uist after Culloden’.

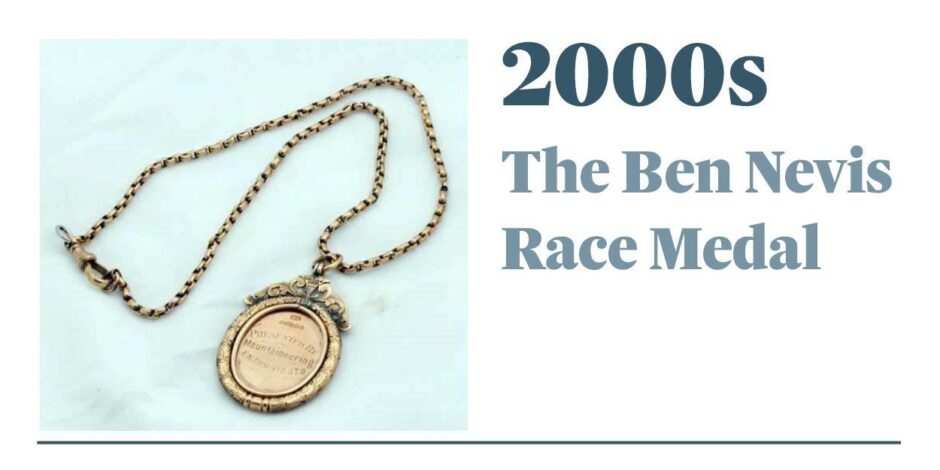

This medal was won by Lucy Cameron in 1902, she completed the race in a record 2 hours and 3 minutes. After her win the race wasn’t held again for 24 years, and when the race resumed women were no longer allowed to compete.

It was not until 1955 that local girl, Katherine Connachie, ignored the ban and competed. The race is still run to this day.

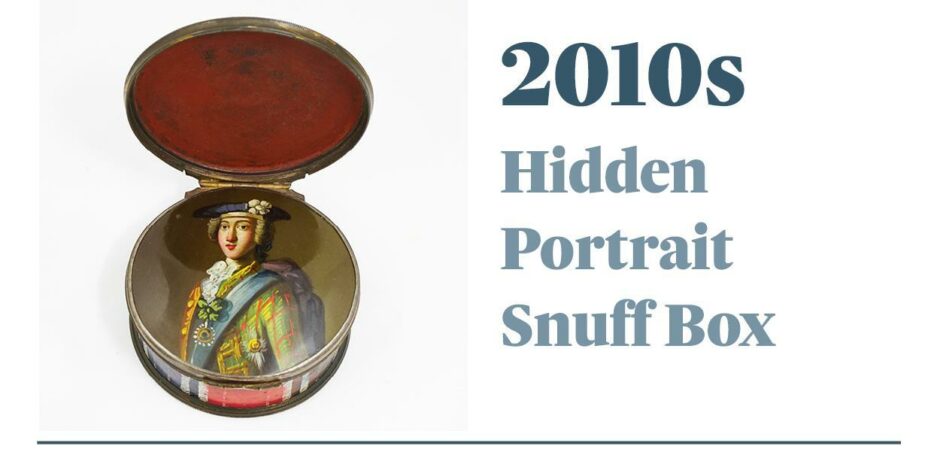

The hinged double lid opens to reveal a finely enamelled hidden portrait of Prince Charles Edwards Stuart in a tartan jacket with Orders of the Garter and Thistle decoration, white cockade and bonnet.

This portrait is a variant of the famous Robert Strange example which likely dates the snuff box to around 1750.

What lies ahead?

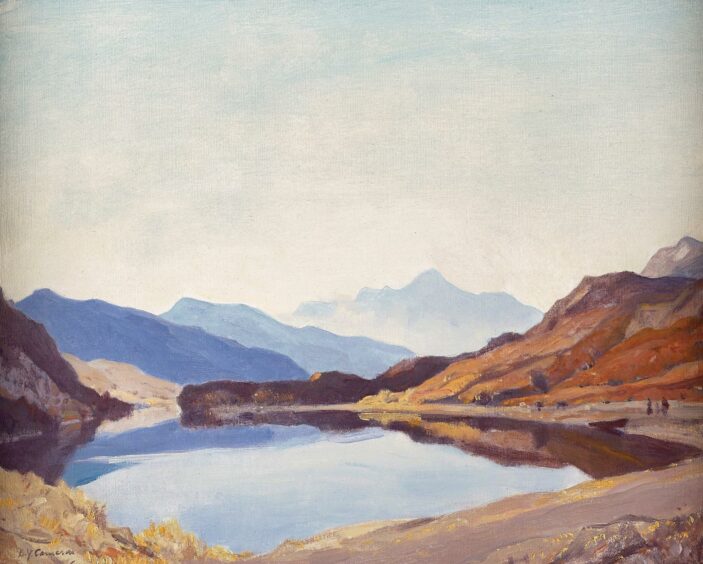

So far this decade, the significant acquisition is a painting by Sir David Young Cameron (1865 – 1945) ‘October in Knoydart’.

Cameron was one of the foremost painters and printers of his day, with close links to the West Highlands.

He was one of the museum’s earliest members.

So what’s ahead to see the museum into its next 100 years?

Dr Chris Robinson, a director of the West Highland Museum Trust, said plans are underway to extend it significantly.

“The idea is to extend the museum onto the High Street with a shop entrance and redevelop the barn at the back of the building to increase exhibition, storage, staff, much needed educational and research facilities.

“It will allow us to tell many more stories and continue to fulfil the ambition of Victor Hodgson that we will be a museum second to none in Scotland.”

The museum will also be staging a celebratory exhibition throughout the year.

You might also enjoy:

Culloden battlefield yields more of its deadly secrets during archaeological dig

Death mask used to create striking digital portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie