Life in Moray must have been beyond compare two hundred years ago.

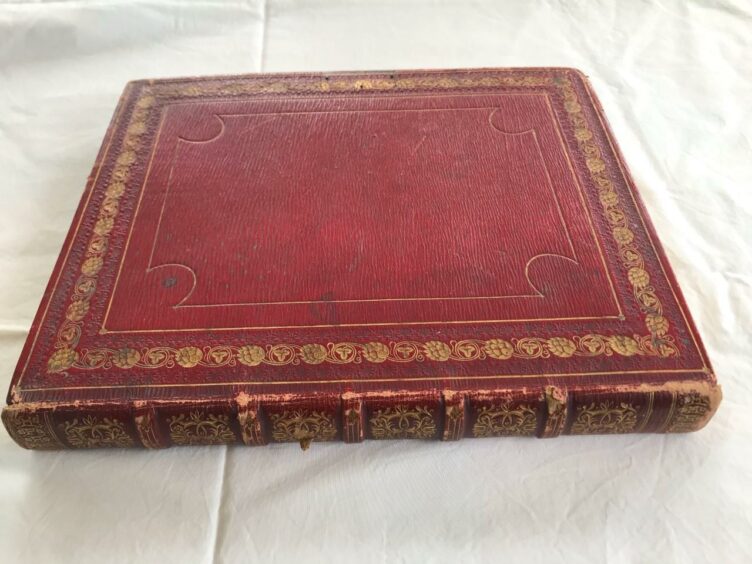

That’s the tacit message in a diary held in the archives of the National Trust for Scotland’s Brodie Castle and now transcribed on the occasion of its 200th anniversary.

It offers an intriguing glimpse into life on the road for the leisured classes 200 years ago, and what it doesn’t say is perhaps more interesting than what it does.

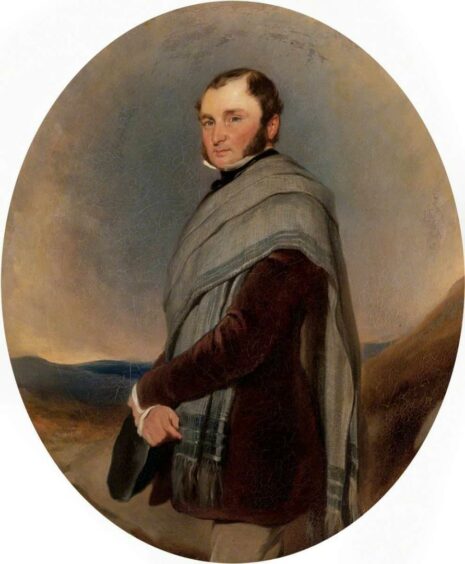

In May 1822, William Brodie, heir-apparent to Brodie Castle, set off on a grand tour of France, Switzerland and Italy, and in the diary he kept, appears to have been distinctly underwhelmed much of the time.

Even Louis XIV’s extravagant Palace of Versailles comes as a let-down, and as for the ungentlemanly dress of Parisians and the remarkably bad singing at the opera — France appears not to have held a candle to the 22-year-old William’s own country.

He set out with his cousin, Elizabeth, 27, and her husband Lord George Huntly, 52.

The Grand Tour

During the tour, they bumped into the Beau Monde of his world all doing their Grand Tours, among others, Sir John and Lady Sinclair; the Duke and Duchess of Hamilton, Lord Sussex Lennox, Viscount Mandeville and Hon. Mr William Keith-Falconer, younger son of 6th Earl of Kintore.

It took the party two days to get to Dover, whence they left by steamboat for Calais.

He dismisses Calais as having little worthy of observation, and the onward journey to Montreuil as dull, ‘only enlivened by some fine peeps of the ocean and the English coast’.

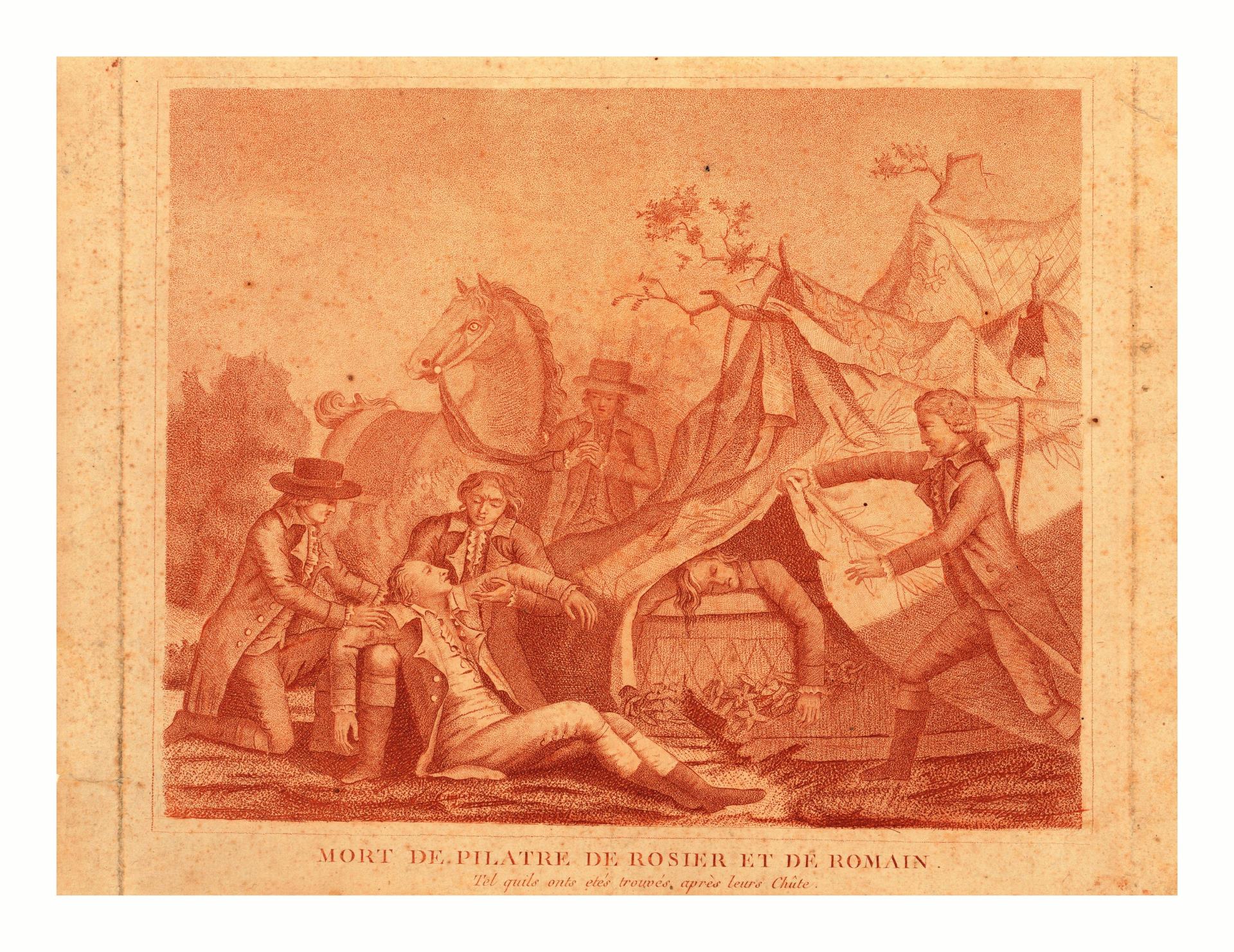

In the hamlet of Wimille, William’s attention is captured by a monument to two balloonists who died there in 1785.

“(The road) contains the remains of the aeronauts Rosier and Pilatre, and a monument is erected to this memory nearly on the spot they perished – it represents a balloon bursting & is erected close by the road side.”

He’s ill-informed, as the balloonist is Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier, who died on the spot with his co-pilot, Pierre-Ange Romain when their balloon caught fire as they were heading towards England, and they fell from a height of 5,000 ft.

The monument can still be seen in the village, and the incident is considered the first aerial disaster.

Napoleon’s ghost

France was at that time recovering from the turmoil of the French Revolution (1789 – 1799) and the spectre of Napoleon, who had died the previous year, was never far from the travellers’ orbit.

William notes: “To the right of the road on approaching Boulogne is the Tower commenced to be erected by Napoleon to commemorate his intended victories over the English – it is unfinished and the scaffolding still surrounding it.”

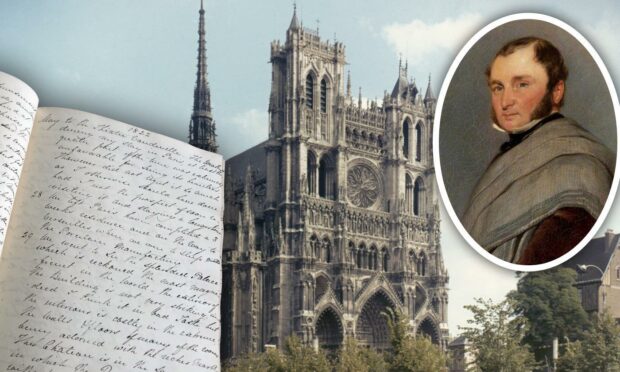

Having found much of the northern French countryside ‘sterile’ and ‘flat and barren’ William is more taken with Amiens which he damns with faint praise: “the situation of Amiens is on an extensive plain, the view however from the Ramparts, which is one of the favourite promenades of the inhabitants, is extensive, & more beautiful than could be expected from its situation.”

But a visit to the theatre later that evening didn’t go well.

“After dinner Lady Huntly accompanied Lord H and me to the theatre, from which however we were soon driven by the combined effects of heat, smell and dirt.”

He warms to Amiens Cathedral however: “I arrived there at the time of morning service, & the grandeur of the place was much increased on that account.

“It is the most perfect cathedral in France, and has been called the chef d’oeuvre of Gothic architecture.”

Much ‘dreary and uninteresting’ travel was to follow before the party arrived in Chantilly, staying at the Hotel de Bourbon.

Here, at last, the young William finds something to be impressed by.

The Hotel du Bourbon Chantilly

“This without exception was the sweetest spot I had yet seen, I may almost venture to say, in my life.

“The Duke of Bourbon is fast restoring the former palace, & hunting seat of the Montmorencies and the Condes, to its original splendour & magnificence.

“The greater part of the Palace was destroyed by a mob from Paris, & a part alone was left to receive this revolutionary plunder.”

Brodie is not much taken with Paris.

The lack of pavements “render walking very disagreeable & tiresome” while bad coachmanship leaves him covered in dirt and constantly jumping out of the way of coaches.

Seeking diversion at the opera Brodie heads to the Paris Opera, for a mixed experience.

“….it is rich & handsome without being handsome – it has not however the same appearance of comfort that our opera has, nor does it strike a stranger with the same idea of grandeur, which is partly caused by the company not going dressed.

“The singing is remarkably bad, & the only attraction is the dancing which exceeded everything I had seen the whole being so well supported by the figurants (groups of dancers who adorn the stage without singing), in which our opera falls off so much.”

A trip to Versailles

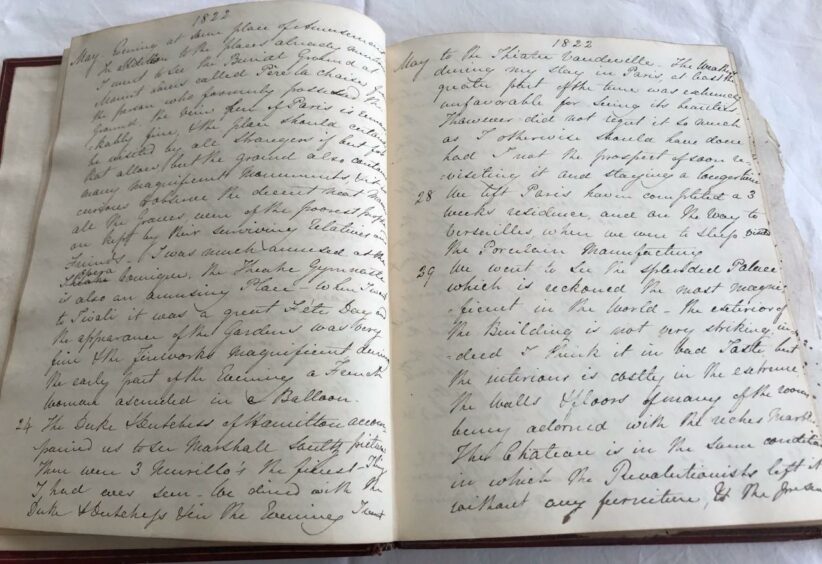

After three weeks of unfavourable weather and sightseeing in Paris, the travellers leave for Versailles.

William’s impressions are not good.

“We went to see the splendid palace which is reckoned the most magnificent in the world.

“The exterior of the building is not very striking, indeed I think it in bad taste, but the interior is costly in the extreme, the walls & floors of many of the rooms being adorned with the richest marble.”

But it was an interesting time to visit Versailles: “The Chateau is in the same condition in which the Revolutionists left it, without any furniture, & the present family have not the means to furnish it as it deserves.”

The Pretender in disguise

In Nantes, he’s shown the house where ‘the Pretender in disguise as a friar concealed himself previous to his embarking for Scotland.’

He’s tickled by his first sight of ladies riding ‘a la fourchette’, astride their ‘ambling nags’ instead of side-saddle; and he gets caught up in an angry rabble booing a despised general after an inspection of the troops and is nearly taken to jail.

Lyon was also not a happy experience.

William found the tone of the town lowered by being full of ‘tradespeople’, with a bad spirit and a ‘great dislike for all foreigners but particularly the English’.

A turn for the worse

The tour proceeded to Switzerland and Italy but matters nose-dive for the already underwhelmed Brodie in September, when Lord and Lady Huntly depart.

The remaining three months of the tour are largely a litany of Brodie’s expenditure as he continues touring iconic sites with nothing more than a note of where they went and what he spent.

Then there were summons to return home by William’s grandfather, who’d had to send him money.

By early January 1823, Brodie was back in Edinburgh on his way home.

Transcribing Brodie’s diary

Brodie Castle’s archivist Jamie Barron took on the task of transcribing William’s beautiful handwriting for easier reading.

He says what the diary doesn’t say is potentially more interesting than what it does say.

“The Brodie family were the poor relations to the Huntlys,” he said. “William had a horrible childhood with his grandfather, and you get the feeling that Elizabeth Huntly, his cousin, has invited him along on their tour because she almost feels sorry for him.

“Perhaps she’s the one encouraging him to write the diary, as it certainly falls off the minute they leave.

“But it seems that the funds disappeared with the Huntly’s departure, and William struggles to keep up appearances with his wealthy circle.”

William’s hard-to-please, world-weary attitude might also stem from a contempt for the Grand Tour itself, a phenomenon from the previous century.

Jamie said: “Grand Tours had ended because of the Napoleonic wars, but now they were over, the tours had started again and seemed old hat to the younger generation, not really the thing to do any more.”

Happiest with family

Virtually the only time William appears happy on the whole trip was when he heard from his family: “I was made happy on my arrival at Tours by receiving a letter from Mother informing me my dear relatives were well.”

William’s widowed mother Ann was resident in Madras with three of his sisters, having married her second husband Col. Thomas Bowser.

Within two years William would become the 22nd Laird of Brodie on the death of his grandfather James, who left him debts of £1 million in today’s money.

Money problems would bedevil the Brodie family for many years, but William prevailed, dying aged 72 in 1873 after 49 years as Laird.

Thanks to a bequest by the ever-caring Elizabeth Huntly, the family’s fortunes were left on a much better footing by the time he died.