The commander of a Royal Navy vessel put in the line of fire during the Falklands War says he has agonized ever since about what happened.

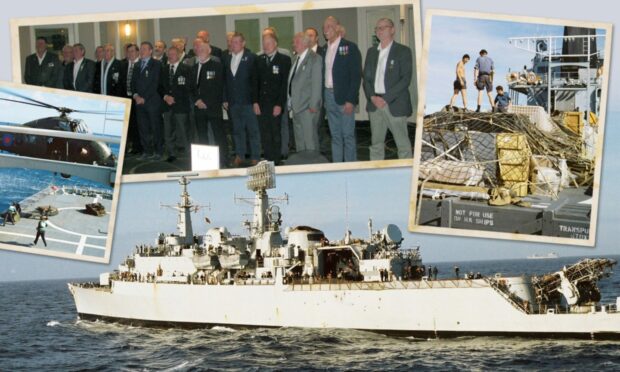

Lieutenant-Commander Colin Hamilton was in charge of Aberdeen-built HMS Leeds Castle when hostilities broke out.

The ship was placed in direct line of Exocet missile fire to protect the war ships in the Task Group inner circle for four days — and had a narrow escape when a missile sank another ship not long after Leeds Castle had left its position to carry out day time duties.

The brand new Leeds Castle was a patrol vessel destined for fishery protection duties in the North Sea, and was in Portsmouth dockyard when “the balloon went up” about the breakout of hostilities.

Recalled from leave

The ship’s company was all on leave, and were recalled pronto.

Colin said: “There were several other ships there including Hermes.

“They were all being stored madly and had been for a few days so the dockyard had gone ballistic.

“There were vehicles delivering stuff from all over the country including torpedoes from Scotland to the Hermes.”

The Leeds Castle company were quietly disappointed when Hermes turned right out of Portsmouth to head for the Falklands while their ship turned left to head for duties in the North Sea.

“I was personally a bit miffed, just having been given a lovely new job commanding Leeds Castle and then seeing Hermes heading south,” Colin said.

“But we spent a beautiful flat calm, sunny week chasing fishermen, then we got a signal telling us to get back to Rosyth and prepare for duties in the South Atlantic as a dispatch vessel.

“I was quite pleased, as were the guys.”

The crew spent a non-stop weekend in Rosyth storing HMS Leeds Castle with “enough food to feed the nation, about 50 tonnes of ready meals, mountains of stores, all the mail, spares for the fleet, you name it.”

They then headed for Portsmouth and had a water-maker fitted to turn sea water into drinking water, before setting course for the Ascension Islands.

It took 40 helicopter loads to take off the supplies flying non-stop for two days before the ship topped up with fuel and headed towards the Falklands.

Speed was of the essence, and the ship was being pushed full throttle to its limits.

Colin said: “We had some very important kit on board designed to confuse Exocet missiles which would be mounted in the helicopters and had to be there by yesterday.”

Blown camshaft

Fifteen hundred miles later the camshaft on one of the main engines blew, leaving Leeds Castle with one engine.

“We sent off a signal saying we’d broken it and needed spares, so one of the staff at HQ rang the manufacturer and said have you got a spare camshaft.

“They said no, but we can sell you a new engine, so the engineer said take the (expletive) camshaft out of it and have it at Brize Norton tomorrow morning – and they did.”

The camshaft was flown out to Ascension and then by Hercules to Leeds Castle, where it and other spares were dropped by parachute into the water.

Not an easy feat, especially as the cloud level that day was very low.

Colin said: “The cloud level was only about 300ft and the Hercules said, sorry I don’t think I can do this, but I said this is very important, please try, come down slowly and we’ll shout as soon as we see you.

Lights through the clouds

“After a while, lights appeared through the clouds, he dropped the stuff, luckily we managed to get it.

“The engineers on board worked for 36 hours non-stop, fixed it and off we went.

“It was a remarkable feat. In retrospect, our engineers should have been recognised for that, sadly we didn’t think about that at the time.”

The incident with the camshaft was a turning point in Colin’s mind for how the war would go.

“I said to myself, ‘we’re going to win this, we can’t possibly not win this war because if we can do stuff like this we can do anything.’”

HMS Leeds Castle spent the war racing round ships in the exclusion zone delivering mail and supplies.

Placed in the line of fire

Her position in the Task Group was ‘interesting’, Colin said.

“We were put in a sector directly between the main body and the Falkland Islands.

“I was amazed because we were not a warship, we were a fishery protection vessel.

“We didn’t have protective measures, electronic warfare, any protection from inbound missiles, we had nothing except a Bofors gun and a couple of machine guns, so we weren’t best suited to protect a carrier, except physically.

“It became perfectly obvious that we were there to take an Exocet if it came in.

“We were four days in that position, although during the day we were racing around quite a wide area to merchant ships and war ships, passing their mail and stores, but at the end of each day we were back on the screen.

“That’s war.”

“Four hours after we left the sector to transfer stores to a merchant tanker, an Exocet flew straight through the middle of the sector and hit SS Atlantic Conveyor,” Colin said.

Commander’s agony

The massive Cunard container ship suffered uncontrollable fire and eventually sank three days later.

Colin said: “I have asked myself a million times since whether it would have been reasonable to take us out.

“The loss of Atlantic Conveyor resulted in prolongation of the war by several days, resulted in the need to move the Welsh Guards and two ships up to Bluff Cove where they were hammered by the Argentines.

“We lost a lot of Welsh soldiers, and two ships.

“Had we remained in that sector we would have lost up to 20 guys and the ship, but the rest would have got off, and that would have saved many lives, much time and much agony.

“Would it have been a fair trade off?

“I would say yes it would.”

Stand down order welcomed

Leeds Castle was sent to help with the transfer of people in Georgia where QE2, Canberra and Endurance were working, alongside Scottish trawlers sent down from Rosyth to mine-sweep.

Her sister ship Dumbarton Castle was now in commission fresh from Hall, Russell & Company’s Aberdeen yard, so the two vessels shared remaining duties.

Thereafter there were mopping-up operations on the island itself, and another trip to South Georgia rolling at impossible angles through icebergs in heavy seas.

It later emerged that both Leeds Castle and Dumbarton Castle had lost their stabilisers during the war due to a design fault.

When the order to stand down came, Leeds Castle headed for Gibraltar for welcome rest and recreation for its 58 strong crew, and then back to England.

“We got into Dartmouth about 6am to pick up mail and no-one noticed, but we did get a nice telegram from the town council apologising, saying they didn’t know we were coming,” Colin said.

“We had a really fine bunch of guys, all Scots from fisheries protection,” he went on.

“They’re known as the Scottish navy.

“They took to it like ducks to water, they loved it.”

Veterans still regularly meet

Leeds Castle veterans, bonded by the Falklands War, still have regular reunions.

This November, they hope to march to the Cenotaph for the first time.

Colin reflected on how things stand for future conflicts.

He said: “The modern day navy has some very fine ships, but not enough of them.

“Could we do it all again tomorrow? I don’t think we could.

“We have the carriers but not enough escorts, and we haven’t got the British merchant traffic to support it.

First rate ships, but not enough of them

“What we have is first rate but not nearly enough of it in my opinion when you look at the problems of the world and what’s coming.”

Colin sees the Far East as being the next area of real concern.

“Threats that are emerging in China Seas.

“Our very close allies the Australians are very concerned about what’s going on with the Chinese are trying to take over some of the islands in the South Pacific.

“Their behaviour in the South China Sea is simply abominable and the future does not look rosy in the part of the world to my mind.”