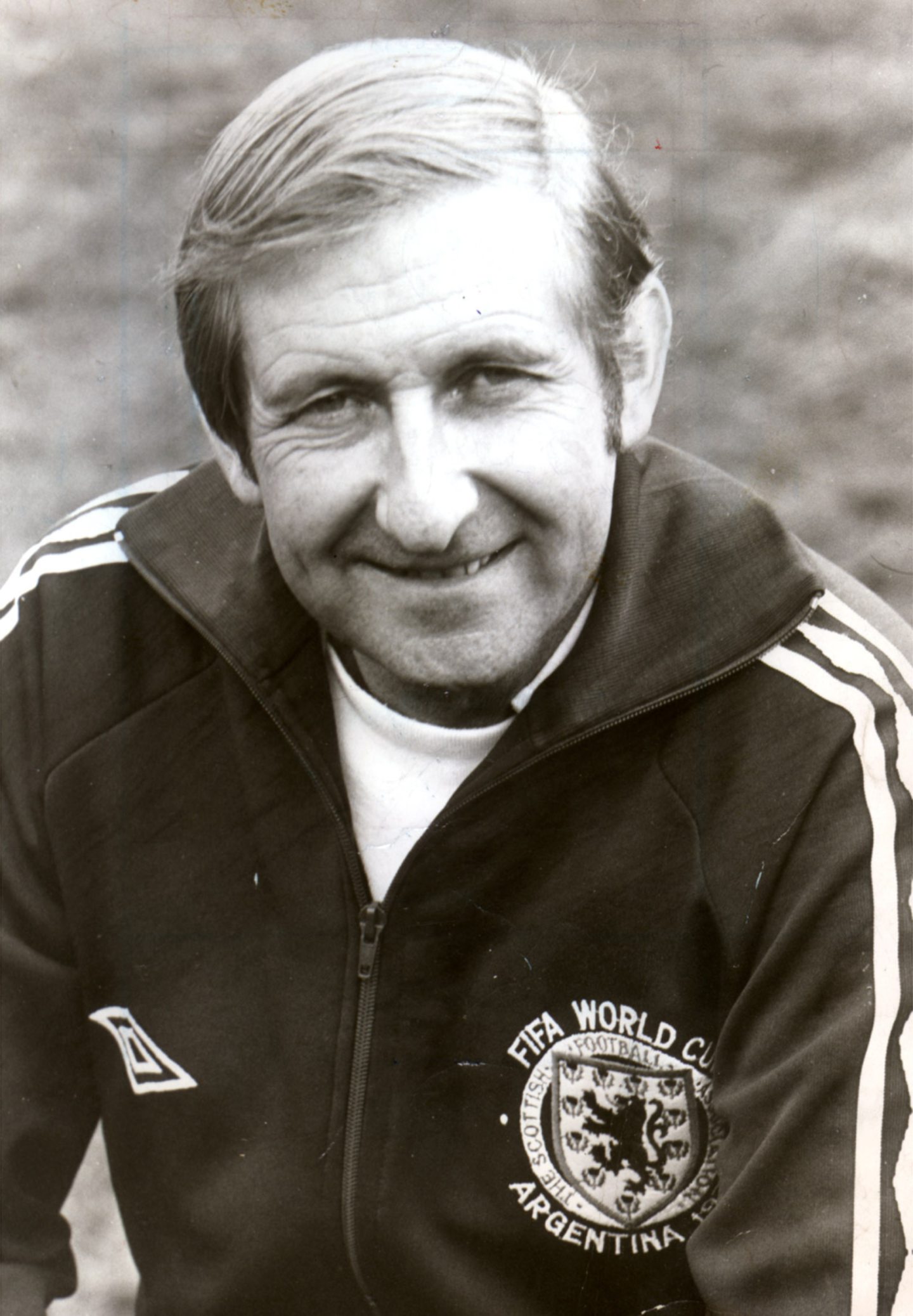

It was full steam ahead on board the Ally MacLeod express when the larger-than-life character was appointed Scotland manager in 1977.

And the journey began with the King of Comedy orchestrating a fabled victory against England at Wembley on June 4 1977.

This was an occasion that was later commemorated or condemned as the match where the Tartan Army invaded the pitch, sat astride the goalposts and ended up breaking them.

At the time, Denis Law responded: “It was just good-natured high jinks.”

And even as the team sat in the dressing room later, Alan Rough looked around him and said: “Good God, these supporters out there really think that we are world-beaters. We’d better not let them down in the future.”

Of course, we’re well aware now of how MacLeod led his compatriots on an odyssey from elation to despair throughout the next 15 months.

Yet don’t forget that, while the journey eventually crashed off the rails, there were thousands of fans who were all too happy to buy their tickets.

Ally soon had the foot soldiers singing

The former Aberdeen boss’s tenure started falteringly with a drab goalless draw against the Welsh in Wrexham.

But MacLeod, an effervescent individual, blessed with an apparently endless stream of pithy one-liners and positive messages, quickly began to weave his magic.

Northern Ireland were demolished 3-0 at Hampden, with a brace of goals from Kenny Dalglish and another from Gordon McQueen.

And, when pressed afterwards for his thoughts on how the trip to London might pan out, he boldly predicted that “his boys” possessed the talent not merely to be the best in Britain, but to be a match for anybody “in the world”.

MacLeod’s squad had barely arrived at their base before Rough was being confronted with reminders of how a string of Scottish goalkeepers had suffered nightmares at Wembley.

Stewart Kennedy had conceded five goals at the venue only two years earlier and the feckless duo Fred Martin and Frank Haffey had let in a combined tally of 16 in two games there – which was sufficiently embarrassing that Haffey emigrated to Australia to escape all the derogatory comments.

Rough recalled: “The papers were full of little else except how ‘the part-time Partick Thistle keeper was in the firing line for fresh humiliation’ and I was sick to death of it.

“Mind you, I didn’t sleep well the night before the game and sought some advice from the Liverpool pair, Graeme Souness and Kenny Dalglish, for whom Wembley was just another big football arena.

“They told me to ignore all the external factors and things I couldn’t control and keep focused on my role and remember I was in the side on merit.”

Getting ready to make history

As the contest approached, MacLeod was in his pomp, relishing the media blitz which surrounded him and lacing his conversation with enough bon mots in his repertoire to satisfy the tabloids, even as he did his best to shield his players from the probing of the press.

In advance, England were favourites and The Mirror proclaimed it was time for “(Don) Revie’s men to deliver”.

After all, Scotland had not won at Wembley for 10 years, since the day Jim Baxter had taunted the World Cup winners on their own turf and been the catalyst for a 3-2 success which, according to Law, was disappointing. “We should have hammered them!”

In the dressing room, the bold Ally gave a typically barnstorming speech, reminding his personnel of their history and heritage and how privileged they should feel to be representing their country in front of the thousands of supporters who had shelled out a small fortune to travel south.

Whereupon, the sides marched out together and stood in the tunnel.

Rough told me: “I stared around and inwardly gasped at the calibre of the company I was keeping.

“There was Ray Clemence, Trevor Brooking, Emlyn Hughes, Mick Channon and Kevin Keegan, rubbing shoulders with Dalglish and Souness and Don Masson, Joe Jordan and Gordon McQueen.

“As the minutes ticked by, I just had to tell myself repeatedly: ‘I am as good as these lads and I have as much right as anybody to be here this afternoon’.

“Then, once we had entered the stadium and it was pretty clear that Wembley had been transformed into a Scottish theatre of dreams, all my inhibitions faded away.

“And when the chorus of ‘Scotland Scotland’ echoed round the ground, I recall having a giant smile on my face.

“If you couldn’t enjoy yourself in that environment, then you were in the wrong bloody profession.”

Looking back at the quality of the visitors’ performance is to be reminded of the class which oozed through their ranks.

Dalglish, as so often, ran the show, while the likes of McQueen and Bruce Rioch were powerful presences, and Willie Johnston weaved brilliantly past his opponents as if they weren’t there.

Nobody could begrudge them taking the lead shortly before the interval when, from a set piece, McQueen rose majestically to head the ball past the despairing Clemence.

That was greeted with a sustained roar from the fans who nearly lifted the lid off the old auditorium and it increasingly turned into a home fixture for the Scots.

Jordan later spoke of how the crowd had lifted them all – “You could hear how much it meant to these people” – and their delirium heightened when Dalglish finished off a chaotic move, sparked by Asa Hartford, to make it 2-0 on the hour mark.

No-one, least of all Revie’s bedraggled mob, could complain.

And yet, Scotland being Scotland, there was a nervy climax when Channon reduced the deficit with an 87th-minute penalty and the hosts sniffed an opportunity to snatch a draw.

But it didn’t happen and they didn’t deserve it.

Cue wild scenes at the finish

The next half an hour is stamped indelibly on Rough’s mind, as thousands of passionate, Saltire-carrying fans swarmed on to the turf and gathered souvenirs and mementoes (including sods of grass).

They were impervious to the efforts of the police and security staff, whose efforts to prevent the onrush were about as effective as King Canute trying to turn back the tide.

Rough said: “As the rampage continued around me, I saw quite clearly there was no malice in the Scottish supporters, just joy at winning at Wembley.

“And their laughter was infectious, even if I do remember thinking there would be hell to pay when I saw them breaking the goalposts.

“Although the game had finished at 4.45 or so, I didn’t get back to the dressing room until after 5.15 because I was so embroiled in that stampede.”

He added: “Eventually, after a torrent of handshaking, hugging, high fives and cries of ‘Well done big man’, I retraced my steps to be with my team mates.

“We were pretty drained, physically and emotionally and we just looked at one another.

“But things had definitely changed. We knew we had won the championship, but it was more than that.

“MacLeod had changed the atmosphere, raised the expectation levels and this was no longer about being the best in Britain.

“By then, the security folk had given up the ghost and handed Wembley over to the kilted hordes.

“I know that, because we had at least a dozen Scottish fans, dressed in tartan, carrying cans of lager and feeling no pain, sitting in the baths with us and nobody batted an eyelid.

“When Ally walked along and saluted the fans at the final whistle, he could have been the Messiah. It was extraordinary.”

The Scots felt good about themselves

The players, though, had made their point.

And, for all that nobody condones pitch invasions and the destruction of property, the fans’ celebrations were rooted in good humour – admittedly helped by the knowledge that their English counterparts had long since departed the scene.

Yes, it might have been riotous and OTT – and there were plenty of newspaper columns and headlines dedicated to Jock-bashing in the days ahead – but Rough still believes there was nothing to be ashamed about.

He said: “There were no stabbings, no murders, nor were scores of innocent victims being rushed to accident and emergency units across London.

“Instead, an invading army with its tongue firmly in its cheek were determined to party as if there was no tomorrow.”

Which was appropriate during a summer when the film Saturday Night Fever was shattering records at the box office.

Just a few days later, Scotland made a controversial journey to South America where they played Chile – where its citizens were being brutally suppressed by General Pinochet – and beat them 2-1.

That was followed by a 1-1 draw with Argentina at the Boca Juniors ground, where Willie Johnston was sent off after retaliating to disgusting treatment – including spitting – by his rivals.

It was a tremendous result for the Scots.

But, of course, it was a different story 12 months later in Argentina.

More like this:

Cobbled streets a riot of colour as Dundee hosted Scotland match in 1896