It goes without saying, creating a garden from scratch needs a long-term vision, hard graft and patience.

But creating a garden from a wind-blasted, barren peninsula where you’re told nothing will grow needs all the above, plus determination, in spades (pardon the pun).

It’s just as well that Osgood Mackenzie was blessed with all those qualities, or the promontory on Loch Ewe where he created his famous garden would still be nothing but shingle, rocks and whatever scrub dare show its head above them.

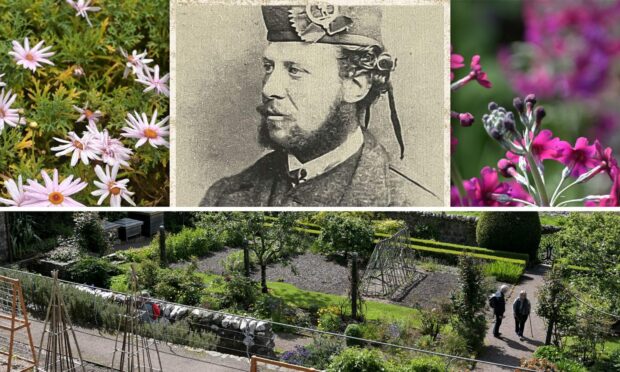

Osgood Hanbury Mackenzie died 100 years ago this year, unaware that his legacy, Inverewe Garden, would go on to give joy and pleasure to upwards of 80,000 visitors annually.

Born into the Mackenzie clan

Osgood was born in 1842, the son of Sir Francis Mackenzie, laird of Gairloch, and his wife Mary Hanbury.

As he was fruit of a second marriage, he was not in line to inherit the estate or titles that went with it.

Mary, widowed when Osgood was a year old, brought him up with his elder half-brothers in Conan House, Easter Ross.

Mindful of Osgood’s lack of land inheritance, she bought him the estates of Inverewe estate and neighbouring Kernsary in 1862.

Osgood wrote: “When I was not yet 20, my mother and I pitched upon the neck of a barren peninsula on the shore of Loch Ewe, on the west coast of Ross-shire as the site of our future home, a site which had nothing which could be called soil or shelter, only a little peat in some of the depressions of the “Ploc Ard” [the ‘high lump’ or promontory].”

The ‘impossible garden’

The high lump was of Torridonian red sandstone, with a raised beach at one end.

It’s closer to the Arctic Circle than St Petersburg and most of Labrador, on latitude 57.8N.

In 1877 Osgood married Minna Amy Edwards Moss, the daughter of a wealthy Liverpool businessman.

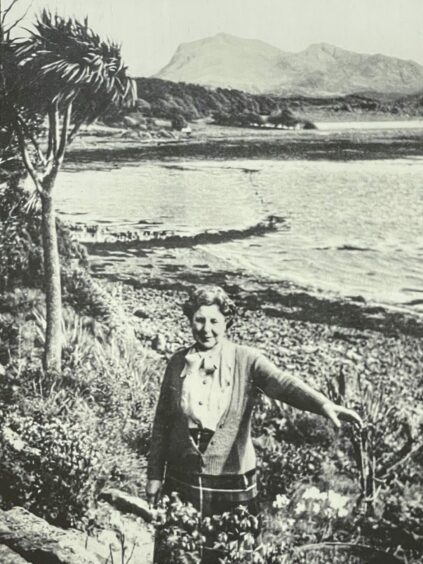

They had one daughter, Mairi, born in 1879 but the couple parted acrimoniously in 1880.

Divorce

Minna was banished from the home and denied contact with her daughter.

There was a gruelling court case before the couple finally divorced.

Minna barely gets a mention in Osgood’s life, but her wealth was an undoubted contribution to the development of Inverewe.

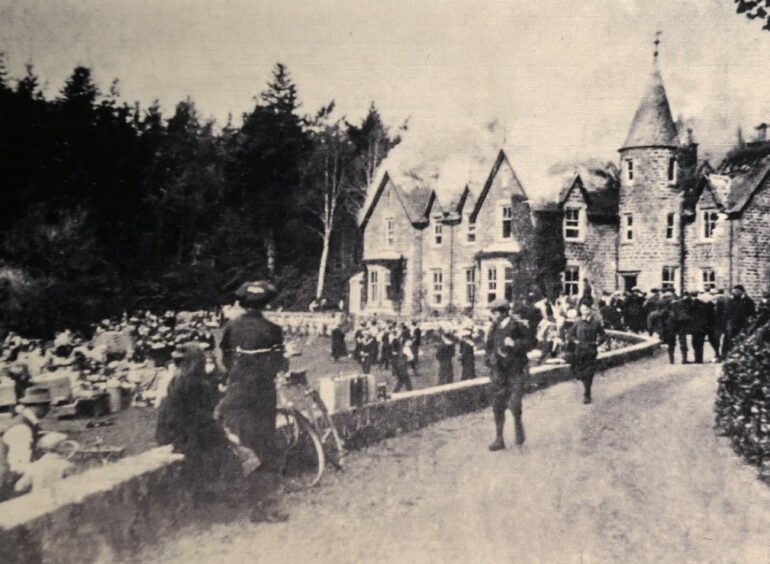

While his mother oversaw the construction of a substantial home, Osgood turned his attention to creating a garden.

First a walled garden for fruit, vegetables and flowers, gouged from the raised beach and complete with sturdy retaining walls and terraces.

Within a few years, the garden was productive and the grand mansion almost complete.

Osgood wasn’t going to settle for just a walled garden

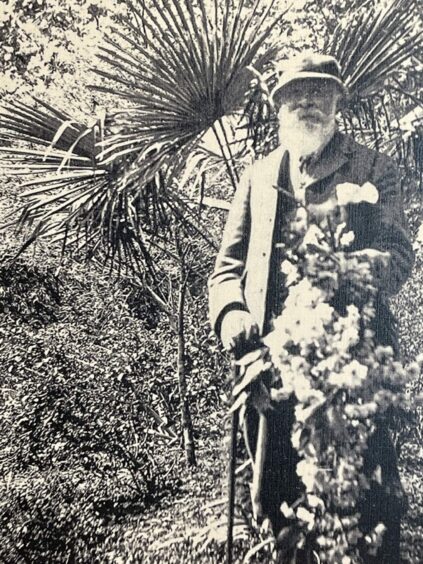

He had toured Europe taking inspiration from the magnificent gardens he witnessed there, and, determined to prove wrong those who told him nothing would grow at Inverewe, he set about planting 100 acres of trees.

When he started out, there was one dwarf willow on the whole of the peninsula, and barely a scrap of peat on the rocks.

By 1880, he had defied the salt-laden gales which roared in from the west and established a young woodland around his house, bringing in soil for every tree, including earth used as ballast on visiting Irish ships.

Establishing a shelter belt

The windbreak and the mildness of the Gulf Stream enabled him to plant the woodland with trees and shrubs from around the world, many rare, so that by the time he died in 1922, Inverewe was internationally acclaimed as one of the great Scottish west coast plant collections.

The house, complete with three-storey round tower, conservatory and breathtaking views over the mountains to the south, boasted three public and six bedrooms, with the ample quarters for an army of servants.

It burned down in 1914, and it wasn’t until 1937 that the current house, built by daughter Mairi and second husband Ronald Sawyer, was complete.

It was built in the Arts and Crafts style, inspired by Ronald’s time in South Africa.

Click on the video above to hear head gardener Kevin Ball talk about the development of the garden, Jacqui Maclennan on being the fifth generation in her family to work in the gardens and guide Ffyona MacKenzie on Osgood himself.

Osgood Mackenzie as a Victorian gentleman

Osgood was a man of his time and class – he loved country pursuits, proudly shooting anything that moved in a way which now seems quite at odds with a countryside lover – and a vigorous proponent of Gaelic and the Highland way of life.

His obituary in The Highland Leader, April 22 1922, says: “Very characteristic of Mr Mackenzie was his intense devotion to home and to the Highlands.

“He loved the people, their language and their traditions, indeed his outlook on life was highly domesticated; he was always happiest when among his own people, fishing, or shooting or attending to his beloved gardens.”

He was a deputy lieutenant and Justice of the Peace for the county of Ross, and involved in all the local public bodies, recorded The Scotsman, while The Ross-shire Journal called him: “A great lover of nature, a skilled, philosophic horticulturist and botanist, and a great lover of silviculture and no mean arboriculturist, he made barren ground bring forth flower, shrub and tree which hitherto had not been deemed possible in Northern latitudes.”

Osgood’s book, 100 Years in the Highlands, written only a year before he died, aged 80, is still in print and although it only devotes one chapter to the garden, gives a fascinating insight into the life of a Highland laird of his time.

Of the garden he writes that the peninsula caught nearly every gale that blew.

“With the exception of the thin low line of the north end of Lewis, forty miles off, there was nothing between its top and Labrador; and it was continually being soused with salt spray.”

It makes his achievements seem even more remarkable.

Inverewe garden after Osgood

Mairi took on the garden after Osgood’s death, but with no heirs, she made the garden over to the National Trust for Scotland in 1952, with an endowment for its upkeep and the decree that it was always to be made available to the public.

This year, NTS celebrates the centenary of Osgood’s death with a new exhibition in the visitor centre, including a fascinating dip into Osgood’s own writings about the garden.

“Many people have no idea what they could do on this West Coast of Scotland if only they would protect!” he wrote. “I am growing palms, Cordylines and tree ferns most successfully.”

To say the least.