They were songs whose simplicity belied the beauty of the melody; lyrics which have become instantly recognisable in pop culture.

Just think about a few of them: “Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away”. Or “Blackbird singing in the dead of night, take these broken wings and learn to fly”. Or “The long and winding road that leads to your door.”

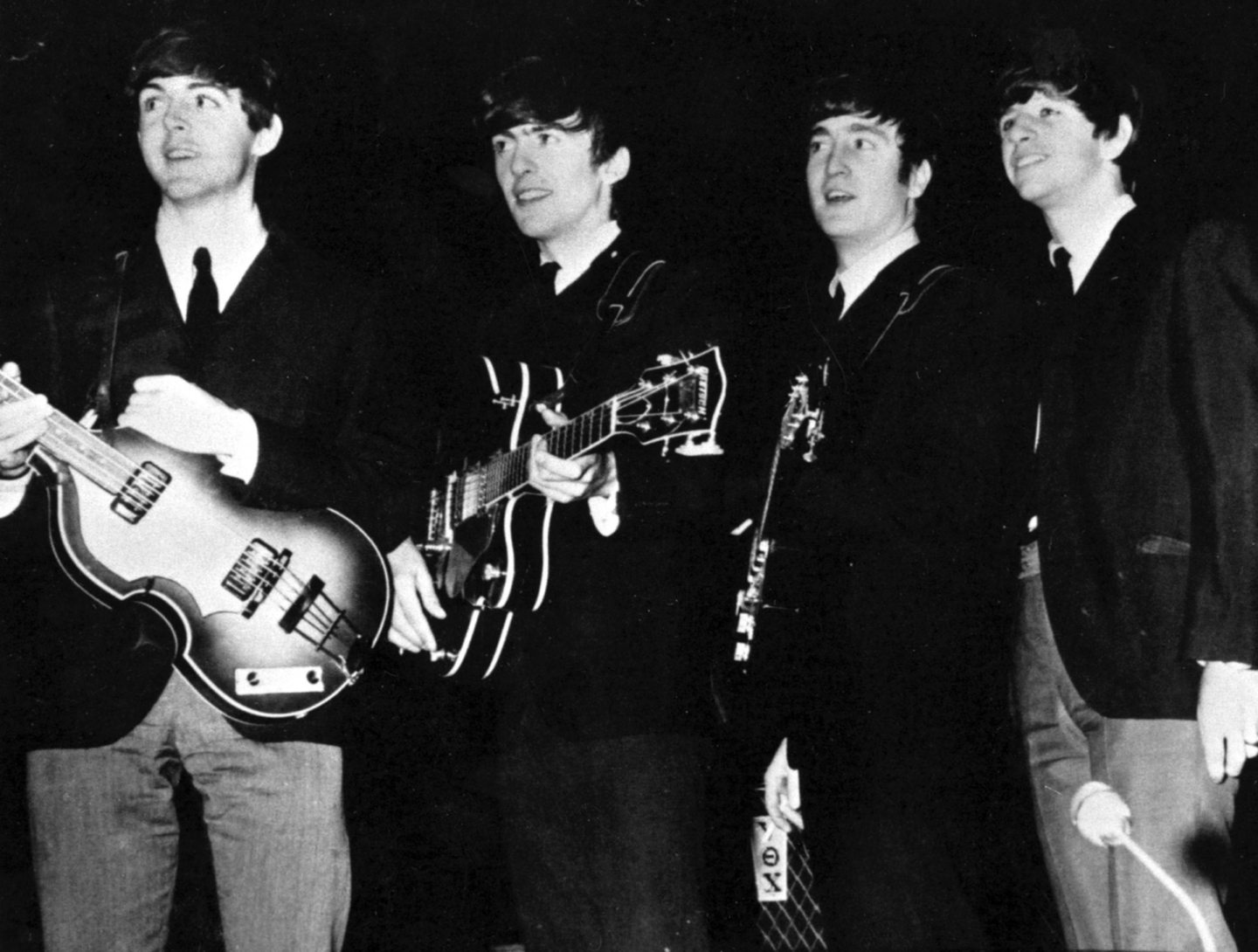

These and so many other classics were created by Paul McCartney, the mop-haired, baby-faced troubadour who was one of the most timeless figures of the Swinging Sixties and yet emerged from The Beatles with the vim and verve to travel to Scotland and record a whole raft of memorable new works.

Years before they were international superstars, he and his colleagues endured mixed responses from audiences in such places as Dundee, Dingwall, Aberdeen and Elgin. And, even though McCartney’s spark was rekindled with Wings in the 1970s, there were those who felt that while he might have survived the Fab Four’s split-up, he was never quite the same talent again.

Yet, undaunted, he celebrates his 80th birthday this weekend as one of the greatest songwriters in the history of popular music. And Scotland has been at the centre of so many of the experiences which have shaped his legacy.

The teenage Macca and John Lennon had to pay their dues on a less than magical mystery tour of the north-east in the early 1960s. This was in the days when they appeared on posters as The Silver Beetles or The Love Me Do Boys as the backing group for acts such as Alex Sutherland and Johnny Scott.

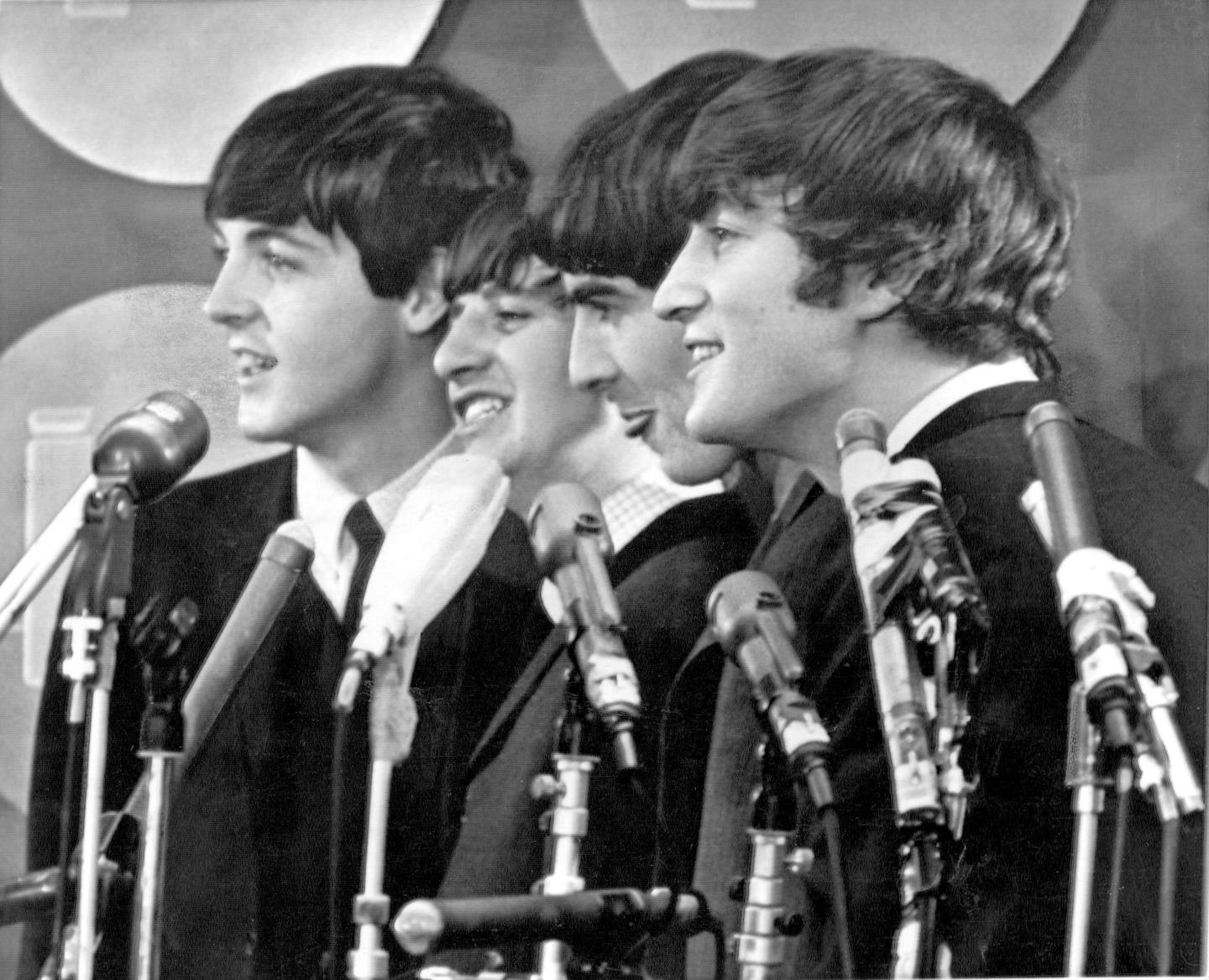

Later, they would inspire Beatlemania and mass hysteria on their tours. Yet there was none of that when they turned up at the Town Hall in Dingwall on January 4 in 1963 and performed in front of fewer than two dozen people, including Billy Shanks, 17, who was less than impressed by what he heard.

He said: “They weren’t very well known at the time. It didn’t register they had recorded ‘Love Me Do’ which went to No 1 in the charts. And the funny thing is that when I went in the door to go upstairs, the doorman said: ‘Before you pay, go up and have a listen’.

“And I looked in the door and thought: ‘No, no, it’s not my type of music.’ I walked out and went to the local village hall five miles away to hear The Melotones. Well, I wasn’t a very good judge, because about three months later, they were worldwide famous and helped changed the face of music.

“The 19 people that did stay on at the event still talk about it to this day.”

Life was a beach for them in Aberdeen

McCartney was a beetle-browed presence on these journeys north, perpetually scribbling down snippets and slivers of lyrics here, there and everywhere.

Yet nothing could rescue him from a fumbling display when The Beatles played their only concert in Aberdeen at the Beach Ballroom – and it took place just two days after their underwhelming reception in Dingwall.

Local man Norman Shearer, who was in a band The Facells, recalled: “The concert was terrific, but not for all of the audience. There are still silly rumours that they were booed off the stage, but that is nonsense.

“They were well received by the bulk of the listeners, and I still have a clear picture of John Lennon standing on the stage with his guitar slung square across his body belting out Johnny B Goode and Roll Over Beethoven.

“My mate, Ian, was also there, with his girlfriend. He remembers they finished with Love Me Do and then the curtains were supposed to close.

“But they didn’t, so the band repeated the song while Paul McCartney was urging the technician to close the curtains. But they finished it again and still they didn’t close, so they sang it a third time and this time – success!

“But that concert was an extraordinary night and one that I will never forget.”

The Beatles attracted an altogether more rapturous reception when they played at the Caird Hall in Dundee towards the end of 1964.

They were superstars by this stage and provided enduring memories with a collection of songs which are now indelibly etched in the music chronicles.

Jimmy Scott, 68, a retired teacher, was among the packed crowd and has never forgotten the fashion in which the quartet whipped up a storm.

He said: “You could tell that they had developed their own identity and the harmonies between Lennon and McCartney sent shivers up your spine.

“It was like nothing we had ever heard before, it was new, it was daring, it was going to places which were beyond our ken. And we were blown away.”

In the following years, the band surged into the stratosphere and produced an extraordinary catalogue of hit singles and albums. At the outset, they were incredibly prolific and somebody in the music press joked: “The Beatles recorded their first album in a week. Their second took even longer.”

McCartney was the quirky down-to-earth personality, with Lennon a snarkier character, prone to sparking controversies by opening his mouth and claiming they were bigger than Jesus before his brain had clicked into gear.

But, even as they moved from the highs of Please Please Me and A Hard Day’s Night to Rubber Soul and Revolver and the epic Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the White Album before rising tensions fuelled the aggravation of Abbey Road and was followed by the angst-ridden disintegration of Let It Be, the ever-shrewd McCartney was already planning for a new beginning.

Forming a new group

As one of the most famous men on the planet in 1970, escape wasn’t easily achieved. Flash bulbs popped a-plenty wherever the former Beatle travelled.

But, even as messy litigation heightened resentments between the different band members, McCartney found himself an idyllic rural retreat where he and his wife, Linda, and their children could enjoy some sort of quiet life.

There were family holidays, but also significant new work in the studio which was constructed in a converted farmhouse at the Mull of Kintyre.

He said later: “Going up to Scotland was real freedom. It was an escape – our means of finding a new direction in life and having time to think about what we really wanted to do. It was a period where I knew I had to move forward.”

After crafting some original solo projects, on which he played all the instruments and displayed his versatility in covering everything from pop and rock to anthems, blues and even a touch of jazz, McCartney eventually decided it was time to form a new group and Wings soon soared into the sky.

In August 1973, the band started rehearsals at the McCartney Scottish farm. And although the tracks for the best-selling Band on the Run were eventually laid down in Lagos in Nigeria, the Tartan influence on the LP was distinctive.

He recalled the origins of one of the most famous tracks: “Jet was actually the name of a pony, a little Shetland pony that we had for the kids on the farm.

“My daughter Mary was born in 1969, so when the song was written, she was four. (Fashion designer) Stella would have been two, so they were little. I remember exactly how the song started when we were in Scotland.

“There was a big hill which had the site of a fortress on top of it, an old Celtic fort. It was an extraordinarily good vantage point. The kind of place where you can imagine the Vikings coming up the hill while we poured oil on them or, if that didn’t work, throw some spears at them.

“I had told Linda I would be gone for a while and, as I lay there on this beautiful summer’s day, I let my mind wander.

“Anyway, I made it up, played it on the guitar, came back to the farmhouse and played it for Linda. I asked her what she thought. She liked it!

“And that was what came out of my afternoon up on the hill. This wasn’t Mount Sinai and I didn’t come back with the tablets of the Law, but I did come back with Jet.”

McCartney has composed so many eclectic songs it’s hardly surprising some have proved more popular than others. And even he admitted he had reservations about releasing a Scottish folk song at the height of punk rock.

An anthem for the ages

But even now, 45 years later, Mull of Kintyre – which featured mass bagpipes and a video shot in Scotland – remains an anthem for the ages.

He said: “Very early on, John had Scottish relatives (in Durness) and he would go up there and stay in a croft and I thought: ‘Wow, that’s really romantic’, so this song (Mull of Kintyre) was a way of plugging into that feeling and being proud of this area where I was living.

“One day, it occurred to me there were no new Scottish songs; there were loads of great old songs that the bagpipe bands played, but nobody had written anything new. So that was an opportunity to see whether I could.

“I thought my way into the minds of travelling soldiers returning home and that dream of coming back to the beautiful country, the beautiful village.

“Sometimes, we do this song in concert when we are in expat places like Canada and New Zealand. We’ve got some security guys who are Scottish and you can see them welling up.

“When the time came to record, I had the local pipe major come up to the house with his pipes, a gentleman named Tony Wilson.

“We recorded the basic tracks, then, a few days later, we had a recording session in the evening with lots of beer for all the boys in the band, although they weren’t allowed to drink it until afterwards, because some of them were quite young and it could have gone horribly wrong.

“And there they were, all dressed up in their pipers’ outfits. It was quite emotional hearing the band play. It was a very fun evening and they loved it (the song) and told me: ‘Oh aye, it’s a No 1 hit.”

McCartney didn’t share their optimism, given the radical change in musical tastes that happened in Britain in the second half of the 1970s.

As he said: “The big thought from me and from everyone was that it was 1977; we couldn’t release the song in these days of punk.

“I mean, it was madness, but I just thought: ‘Well, sod it’. And even though I was a Sassenach, it became a big hit, it ended up spending nine weeks at number one and I think it is still something like the fourth best-selling single in the UK ever. And the strange thing is that even punks liked it.

“One day, Linda and I were in traffic in London in the West End and there was this big gang of punks who looked very aggressive and we were crouching a little bit, trying not to get noticed and thinking ‘What are they gonna do?’.

“And then they saw us, and one of them comes to the car, so I wound down the window a bit and he goes: ‘Oy Paul, that Mull of Kintyre is f****** great!”

Paul McCartney is still writing, still working in the studio and performing live. One of the all-time greats with a guaranteed place in the pantheon.

Happy birthday Macca.

More like this:

Beatlemania was banned by Aberdeen schoolmaster in 1963

Paul McCartney brought out the Dundee cake for wife Linda at Caird Hall gig in 1975

Conversation