It was less the bridge of sighs and more of howls of anger from those who led the campaign against “exorbitant” tolls on the road to Skye.

And even now, 30 years after construction began on the controversial Skye Road Bridge project, those who led the protests and were prepared to face the courts and even a prison sentence are convinced their cause was justified.

A variety of road and rail connections to Kyle of Lochalsh had been constructed towards the end of the 19th Century and various parties had proposed building a bridge to the island. But the island’s remoteness and small population meant the costs involved remained prohibitive.

By 1971, two 28-car ferries carried more than 300,000 vehicles a year and the rising demand renewed calls for the creation of a road bridge. Yet nothing happened quickly and several mooted proposals withered on the vine.

Finally, though, towards the end of June 1992, work began on the £25m structure, following confirmation by the Scottish Office that the venture – funded by tolls – could go ahead. But the announcement by Ian Lang was merely the beginning of more than a decade of acrimony and arguments.

Mr Lang’s green light for the venture was not exactly whole-hearted. As the Press & Journal reported on June 25: “The Scottish Secretary has refused to make any major concessions over the controversial plan to pay for the bridge by charging high tolls over a period of 15-27 years.

“He also rejected a number of recommendations made by the Scottish Office Reporter, who carried out a public inquiry into the bridge plan.

“The Reporter’s recommendations that the [Conservative] government should make an annual financial contribution to the costs of the project and should name a date when the tolls will end were both turned down.”

Almost immediately, the touch paper had been ignited. Skye and Lochalsh district councillors, who met in Portree, expressed concerns about Mr Lang’s refusal to pledge extra financial assistance to the project.

They warned that many residents on Skye had intimated they were not prepared to pay excessive tolls on an indefinite basis. Some had gone further and insisted they would not pay the levies at all and damn the consequences.

Council chairman John Farquhar Munro said: “This decision means the Skye Bridge will carry the highest tolls in Britain, so we are deeply disappointed that the Scottish Secretary did not take this on board.

“We shall continue to press for a change of heart on this important issue.”

The Press & Journal’s editorial anticipated there would be conflict in the future and was less than impressed with Mr Lang’s decisions.

The paper said: “It would seem the only winners from the inquiry have been the otters [which were granted greater protection], although that may be a touch cynical. As for the tolls, efforts by the Reporter to gain more clarity on them have been rebuffed, which is unlikely to endear them to the islanders.”

This was putting it mildly. In the months ahead, many people in Skye spoke of their determination to fight as far as they could and into the courts if it was required. Campaign groups were established, petitions were signed and it bore some of the hallmarks of the Can’t Pay Won’t Pay anti-poll tax crusade.

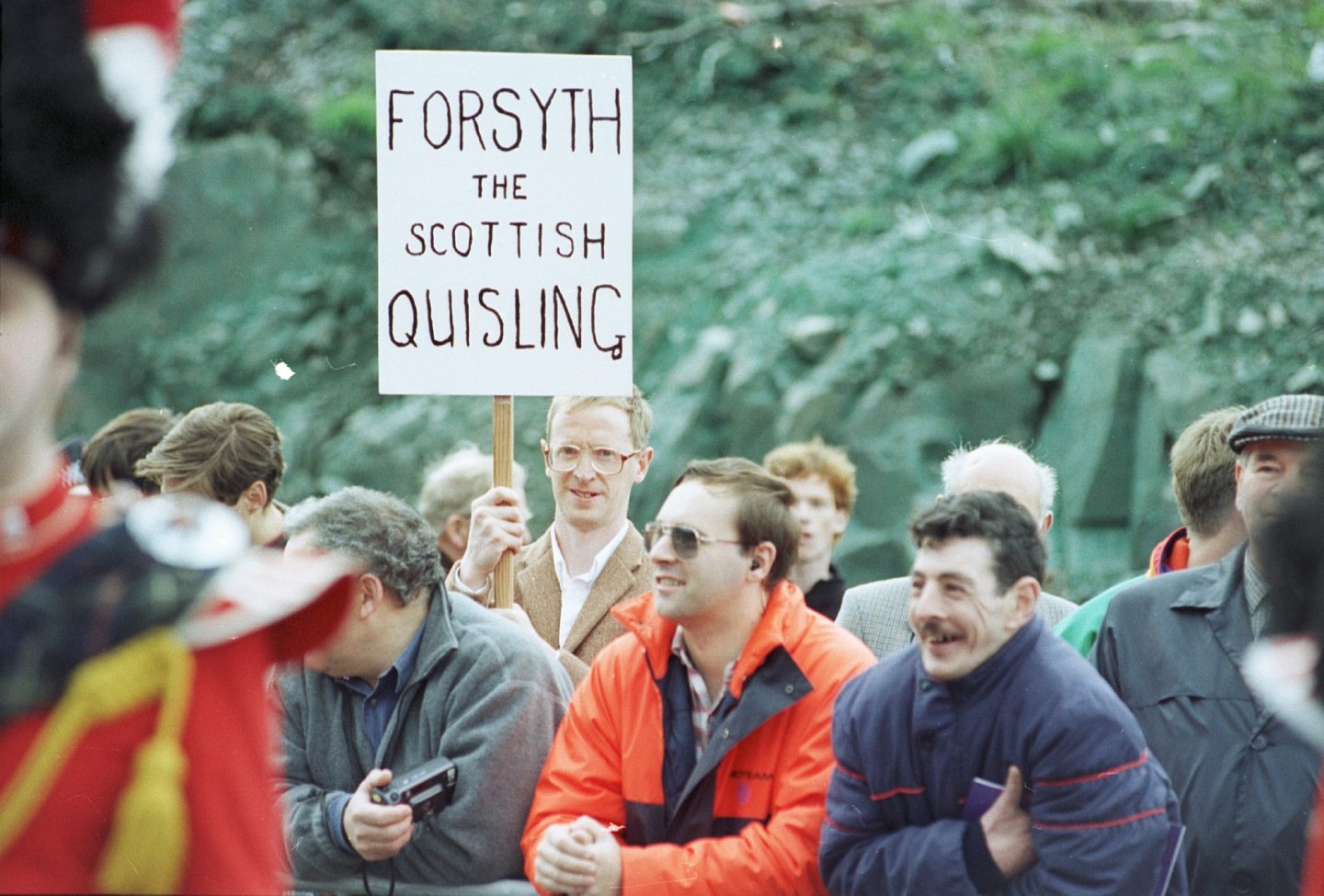

Even when the bridge was opened by Secretary of State for Scotland Michael Forsyth on October 16 1995, some demonstrators branded him a “Quisling” and there was never any prospect of them losing heart. Quite the opposite.

The tolls started at £4.30 for all cars and £25.40 for buses, though they escalated upwards in the next years, as the backlash spiralled.

A transport watchdog’s report in November 1995 sparked fresh fury when it described the charges as “fair”, while arguing that motorists who lived in Skye and Kyle should not pay more than £1 for crossing the bridge.

Ross, Cromarty and Skye MP, Charles Kennedy [the future leader of the Liberal Democrats] was among those who slated the findings.

He told the P&J: “This is a bitter damp squib of a report. The committee has provided what will be welcome cover and camouflage for those at national level who are still trying to defend the injustice of the tolls.”

In one aspect, the new structure was an unqualified hit with locals and tourists alike and it recorded traffic of 612,000 vehicles, a third more than the ferries’ official numbers, during its first year in operation.

But that figure was matched by the depth of opposition to tolls with around 500 being arrested and 130 convicted of non-payment in the same period, including men and women of all ages, including pensioners.

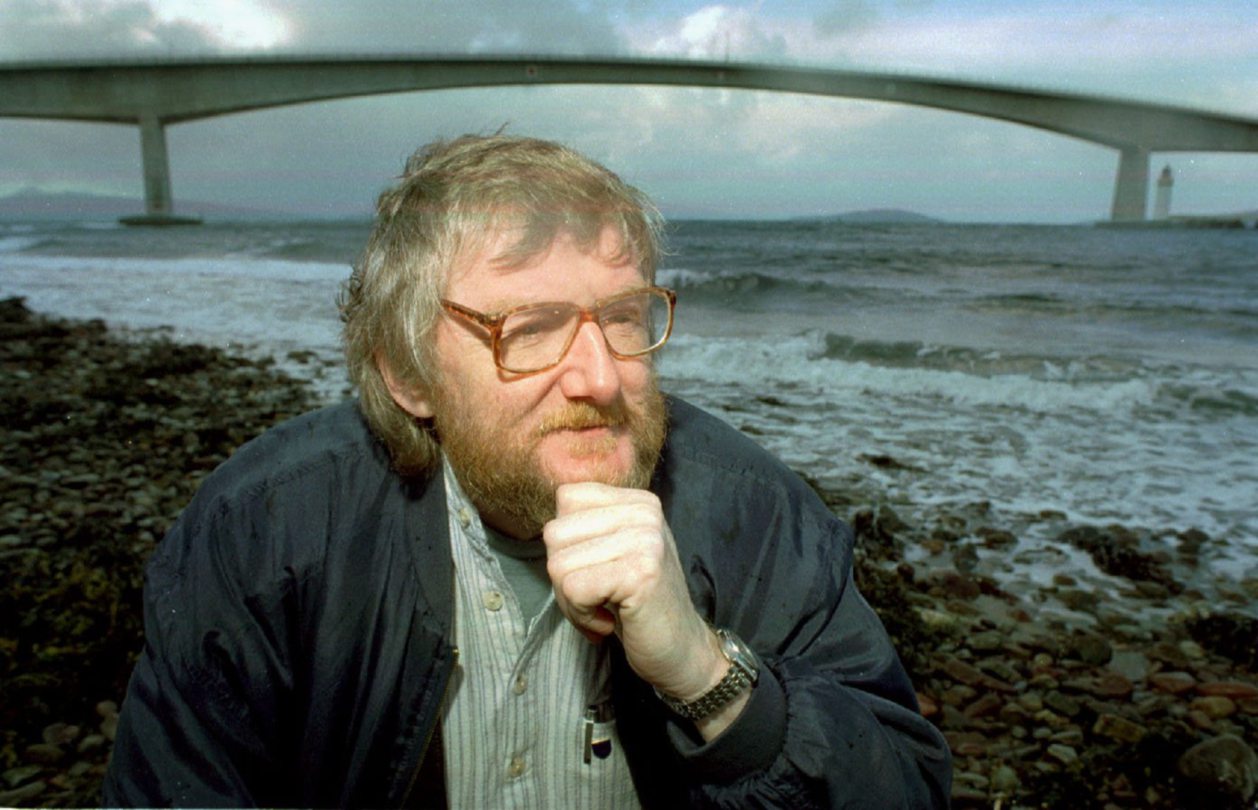

As months passed, amid scenes which resembled a true-life Ealing farce, it gradually turned into a battle of wills between law officers and the likes of Robbie the Pict, the larger-than-life character and godfather of actor Leonardo DiCaprio, whose name became synonymous with the protesters’ causes as they embarked on a lengthy struggle with the establishment.

Those charged with non-payment were forced to make the 140-mile round trip to Dingwall sheriff court, which required them to cross the bridge again.

Predictably, the majority of them refused to pay once more, incurring a further criminal charge, as the proceedings descended into pandemonium.

Andy Anderson, the secretary of Skye and Kyle Against Tolls, was arrested several times and jailed for 14 days for refusing to return to court.

‘This is an affront to justice’

Robbie argued passionately that the tolls were against natural justice. But, in an explosive interview with the P&J, he went even further.

He said: “We now have a toll tax in Scotland and we are being used as a colonial political laboratory. If we allow this private finance initiative to be established on Skye, it will set a precedent for the rest of Scotland and there will be private roads everywhere we go. We have to resist it at all costs.”

Their patience and perseverance remained undimmed as the Conservative government was swept away in a torrent of Labour gains in 1997.

Following the election, the Scottish Office introduced a scheme whereby tolls for locals were subsidised – the scheme cost a total of £7 million – but this was dismissed as a fudge by Robbie and his colleagues who had fathomed that the wind was in their sails and stuck to the principles.

To them, it was irrelevant whether the toll was a penny, a pound or a fiver. They weren’t paying.

Eventually, after the creation of the Scottish Parliament in 1999, the Scottish Labour Party formed a coalition with the Scottish Liberal Democrats, who had made abolition of the Skye Bridge toll one of their priorities.

With responsibility for the country’s road network transferred from Westminster to the Scottish Executive, increased political pressure was placed on the issue which had annoyed so many Highlanders. And finally, in 2004, Jim Wallace, the Enterprise Minister, announced the bridge would be bought and tolls abolished by the end of the year.

Yet it wasn’t all sweetness and light in the aftermath. A BBC Alba documentary in 2019 revealed the tensions which had burbled beneath the surface on both sides, with the court cases causing stress and worry for the islanders, while the local Procurator Fiscal revealed he had suffered a nervous breakdown as a result of the whole imbroglio.

Robbie, for his part, is now in his 70s, but remains defiantly unbowed and is still trying to have the penalties struck off the record.

He said: “I was charged 129 times and 25 of them were made to stick and they are still live. These have to be expunged. This has cost me 25 years of my life and it has made a big dent on my family.

“The people of Skye were being quite brave to confront the police at the risk of going to court and the likelihood of conviction, but if you are not happy about things, then you have got to do something about it.

“Imperialists are not known for being kind if you just sit in your armchair.”

More like this:

From Hollywood to the Highlands: Who is Leonardo DiCaprio’s eccentric Scottish godfather?