Ghosts walk through the old pictures of Dingwall railway station.

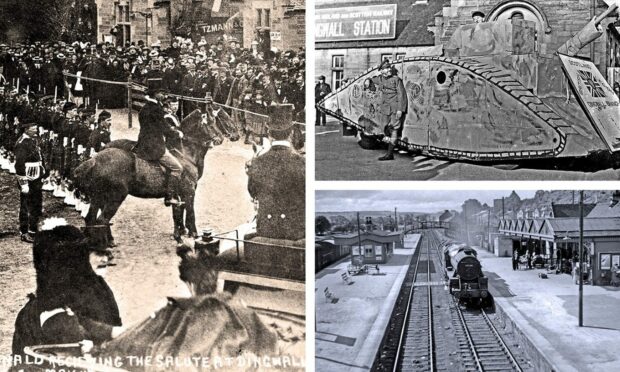

There are Seaforth Highlander troops on the platform in 1915, prior to travelling to England and thence to France during the Great War; a British Legion tank outside the building with a captivated crowd excitedly inspecting this fascinating artefact; and a formidable Black Five class locomotive simmering on the northbound platform in the days of British Railways.

There is also the tragic reminder of the rise and fall of one of the Highland town’s most famous residents, Sir Hector Macdonald, who rose from humble origins to become the commander of all British troops in Ceylon – modern-day Sri Lanka – only for his achievements to be overshadowed by a sex scandal which eventually led to this proud soldier killing himself in Paris.

These photographs provide a time capsule to a past which feels like another world. Yet they also reveal how little has changed in many people’s obsession with the minutiae of machinery, motors and what makes things tick.

Dingwall is probably most famous these days for the exploits of its local football team Ross County who surged to glory in the 2016 Scottish League Cup final with a memorable victory over Hibs.

Yet, unlike many other communities in the north of Scotland, which were grievously affected by the Beeching Cuts in the 1960s, the town still boasts a busy railway station which dates all the way back to June 1862 when it was opened by the Inverness and Ross-shire Railway, quickly absorbed by the Inverness & Aberdeen Junction Railway, and subsequently became a pivotal part of the newly-formed Highland Railway in 1865.

Passengers flocked to buy tickets

There was no shortage of competition in those days, and no dearth of customers either, with the line being extended to Invergordon and to its final destinations of Wick and Thurso in 1874. This was a golden age for those who relished the railways and it’s difficult now to envisage the sheer amount of traffic which passed through Dingwall at the height of its popularity.

That’s why the work of author, Bernard Byrom, is to be cherished. In his new book Old Dingwall, he has meticulously unearthed its Victorian heyday.

As he explained: “The station became a junction in 1870 when the Dingwall and Skye Railway opened as far as Strome Ferry and, at that time, it became a four-platform station with a bay being added at the north end.

“When a branch line to the spa resort of Strathpeffer was opened in 1885, the traffic increased to such an extent that a handsome new station was built the following year for northbound trains and it is still in use today.

“The Strathpeffer branch was closed to passenger traffic in 1946, but it remained open to freight traffic until 1951. And the lines to the far north and the Kyle of Lochalsh survived the ‘Beeching Axe’ and are still operational.”

Public protests and a campaign by officials to save services in Dingwall proved invaluable. Many other routes in Scotland were not so fortunate.

However, it wasn’t just trains that sparked the imagination of the locals. The public flocked to the site in large numbers to celebrate the coronation of King George VI in May 1937 and Dingwall staged a large-scale procession as part of the festivities which showed no little enterprise and initiative.

The Royal British Legion were among those who put their heads together and created a life-sized model of a tank, which was sufficiently impressive in scale that many youngsters were determined to investigate further even as the vehicle stood parked outside the railway station.

Just a few years, with Britain at war again with Nazi Germany, some of them found themselves in tanks again and, this time, it was in deadly earnest.

Old Dingwall depicts the exuberance of youth and the transformation which has taken place during the last two centuries – but while there are happy scenes of bowlers in action and children frolicking, and a resplendent aerial shot of the town as it looked in 1960, there is also tristesse in these pages.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the chronicling of the dramatic life and times of Hector Archibald Macdonald, who was youngest of five sons born at West Rootfield Farm at Mulbuie. Sturdy, strong and fiercely independent, he was determined to pursue a career in the military and at the age of 16 in 1869, pretended to be older to join the Inverness-shire Highland Rifle Volunteers.

He soon made his mark on those around him and, just a year later, enlisted in the 92nd Regiment, Gordon Highlanders. He was destined for greatness.

In the decade ahead, he rose swiftly through the ranks, fought in the Second Afghan War from 1878 to 1880 and was commissioned Second Lieutenant.

Macdonald’s popularity increased as he was involved in combat in Egypt and the Sudan, where he achieved further promotions and earned the nickname “Fighting Mac”. In September 1898, he commanded an Egyptian brigade so effectively that he was promoted to the rank of Colonel, and he had become a national hero, been accorded the thanks of Parliament, and was immortalised as the kilted soldier on the label of countless Camp Coffee bottles.

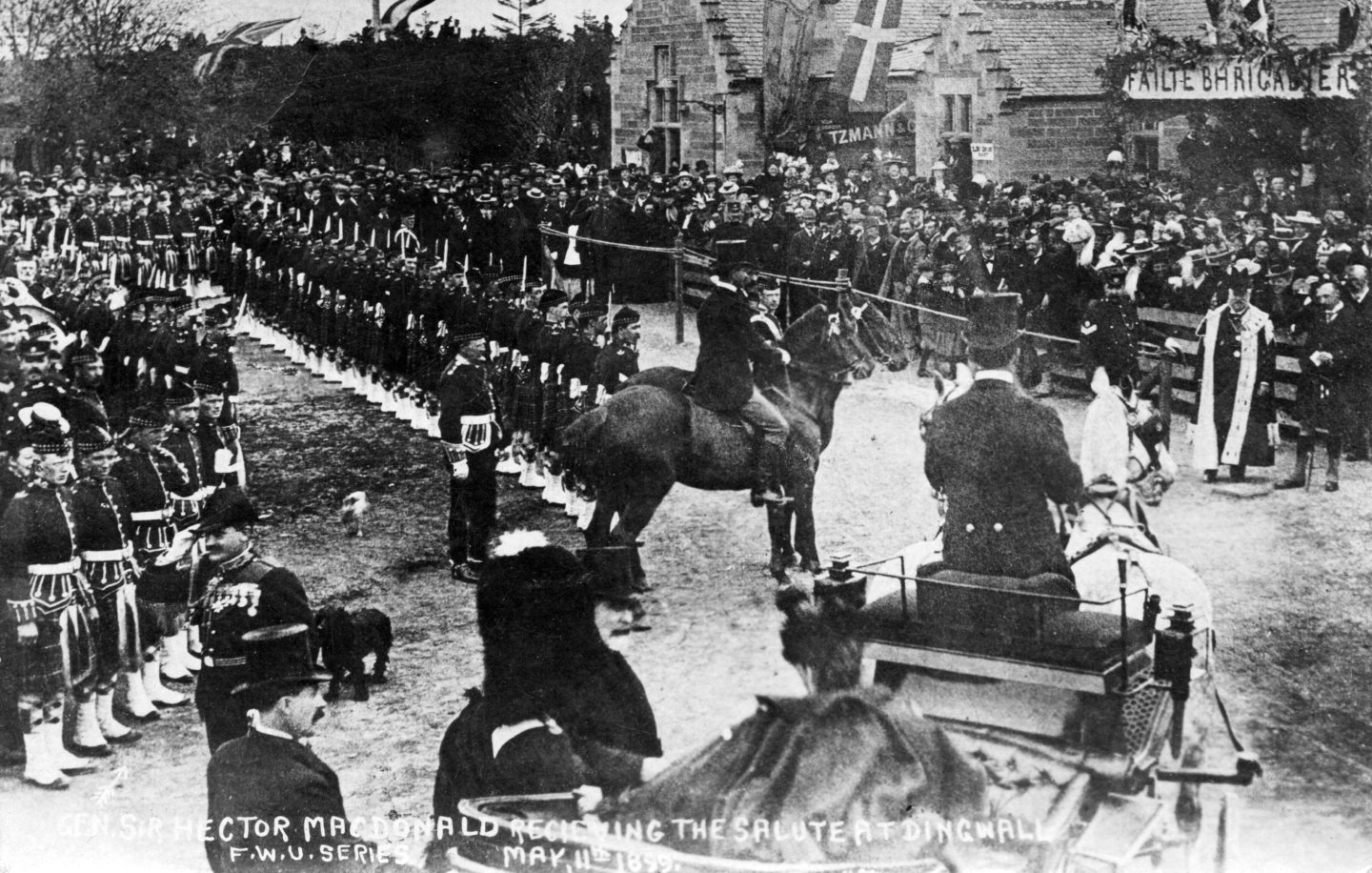

No wonder he was hailed as a conquering hero when he was granted the Freedom of Dingwall in May 1899 – which is captured for posterity below – and received a knighthood two years later. This was his shining period.

But all that was forgotten during the next traumatic decade.

Mr Byrom said: “Sir Hector went on to fight in the Second Boer War and, afterwards, was made commander of all British troops in Ceylon. This was at a time when military officers were almost exclusively drawn from the nobility and upper classes, usually commissioned after being trained at Sandhurst.

“Macdonald’s rise through the ranks from Private to Major-General on merit alone aroused jealousy and resentment among some of his peers.

“His popularity was not helped when he declined the social invitations of the British community in Ceylon and consorted instead with the locals.

“Rumours began to circulate that he was patronising a ‘dubious club’ attended by British and Sinhalese youths and was having a sexual relationship with two teenage boys. When allegations from prominent members of the colonial establishment followed, the Governor advised him to return to London.

“Macdonald did so, but Lord Roberts, the commander-in-chief of the Army, advised him to return to Ceylon and face a court martial to clear his name.

“He agreed to this and started out on the journey, but the morning after a stop-off in Paris, the New York Herald reported that he was returning to face ‘serious charges’; somebody [inside the establishment] had sold the story.

“The shame was too much for the proud soldier to bear. He went up to his room, put a pistol to his head and pulled the trigger. The date was March 25 1903 and he was 50 years old.”

His suicide was a tremendous shock to the British public. And a government commission report into the tragedy concluded that he had been “cruelly assassinated by vile and slanderous tongues” and fully acquitted him.

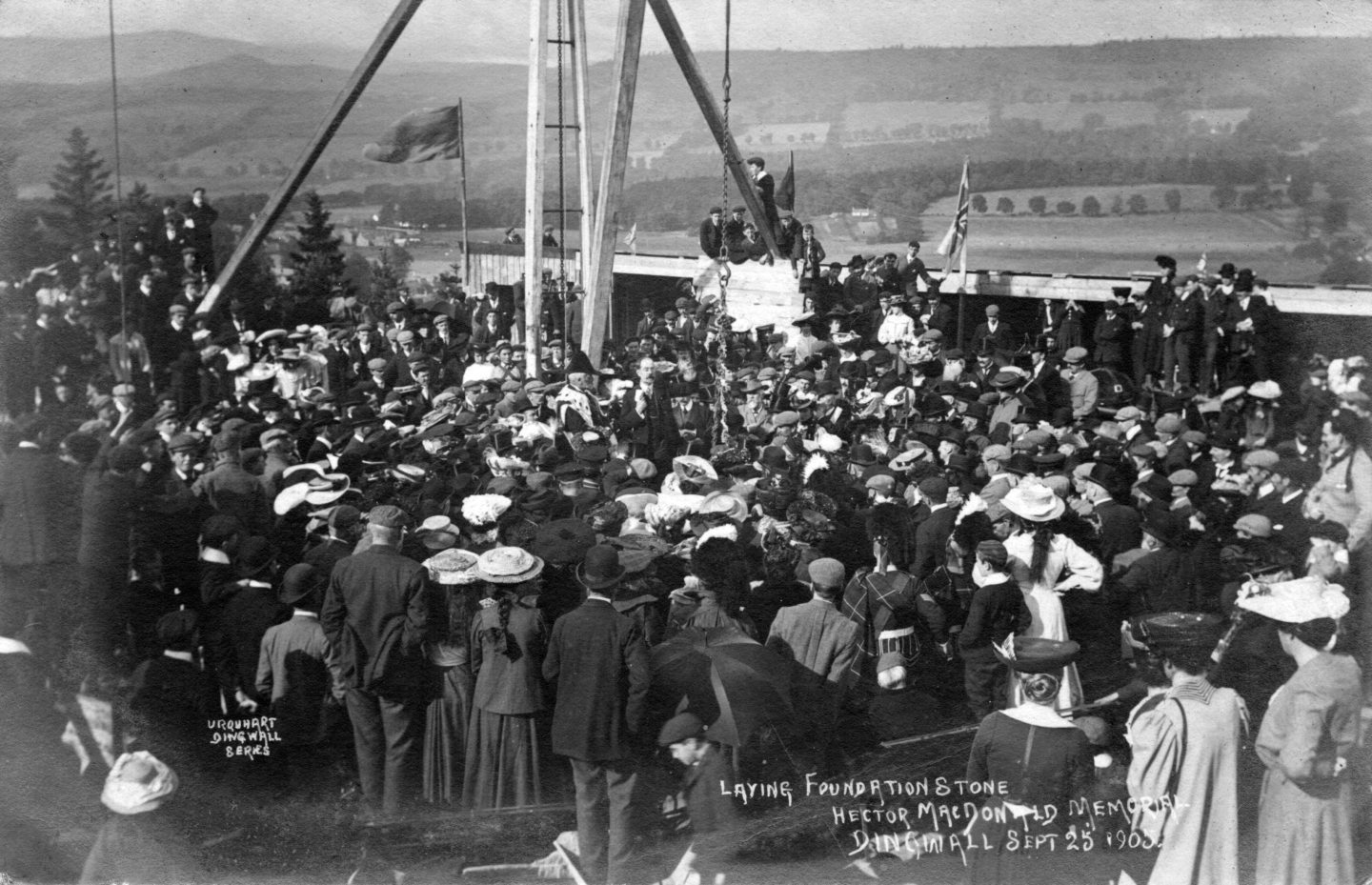

To many people, especially in the Highlands, he remained a heroic figure and the foundation stone of the Hector Macdonald National Memorial was laid with great pomp and ceremony in Dingwall in September 1905.

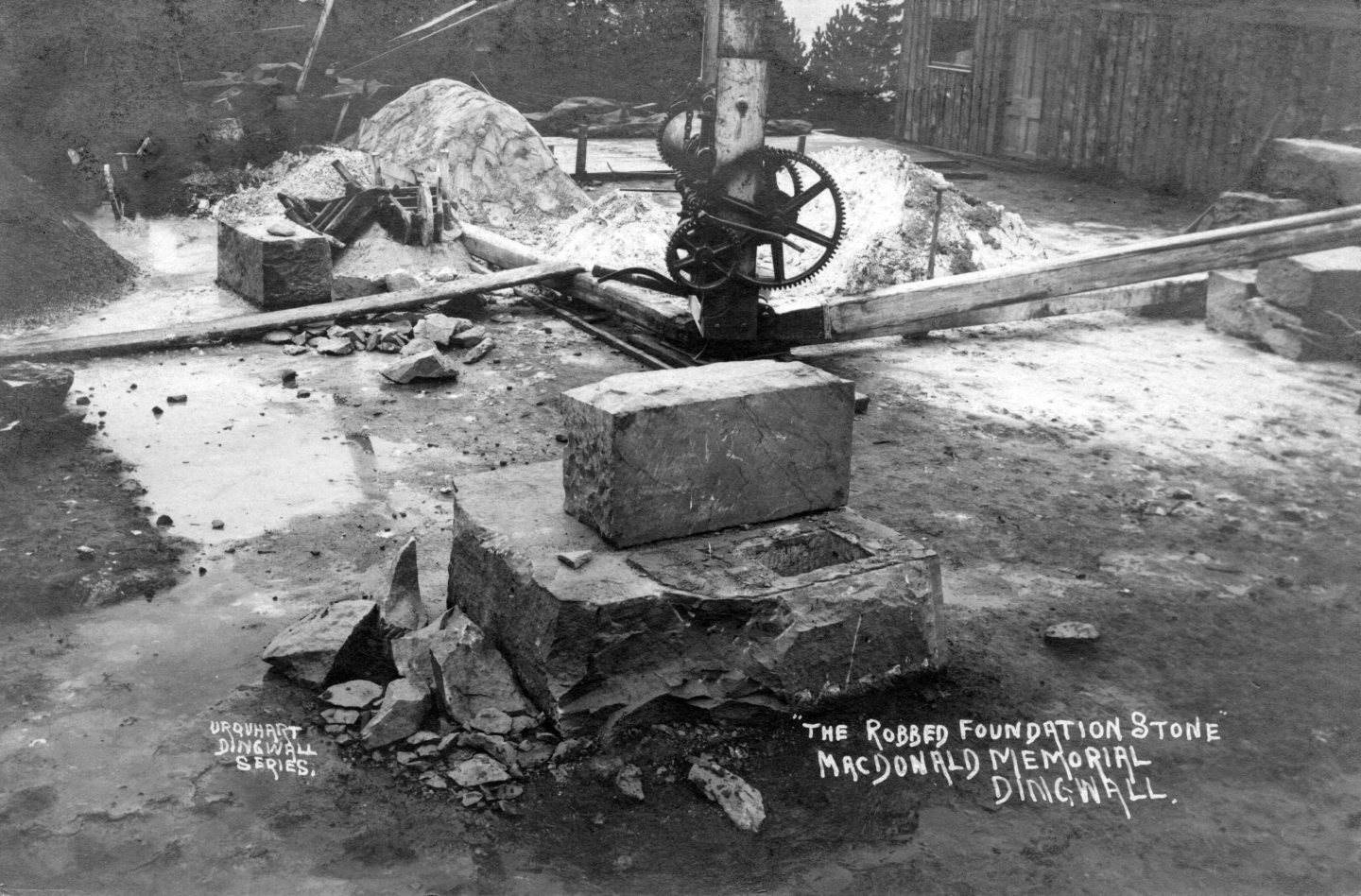

And yet, just two months later, two workmen employed on building the memorial discovered that the foundation stone had been turned over completely and a box of precious mementoes had been stolen.

It was a tawdry end to the saga of a man whose reputation had been trashed.

History comes alive in these old postcards and black-and-white photographs. All emotions are here and, while it wouldn’t have been any consolation to Sir Hector, a national memorial was constructed in his honour in May 1907.

The 100-foot baronial tower overlooks Dingwall from Mitchell Hill and is a permanent reminder of one of the most significant characters from the town.

Old Dingwall is available from Stenlake Publishing.

Conversation